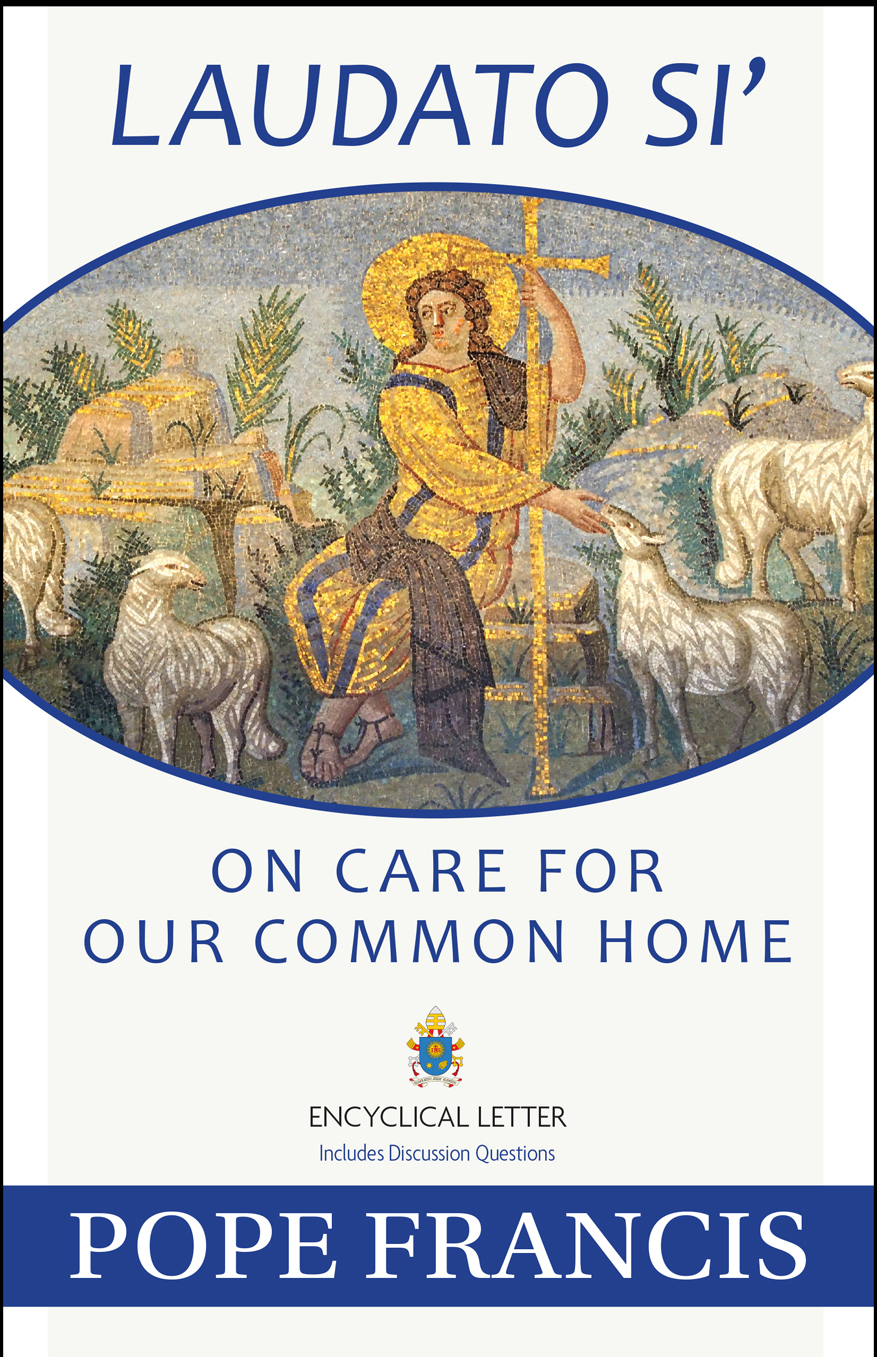

Laudato Si

On Care for

Our Common Home

Laudato Si

On Care for

Our Common Home

Encyclical Letter

Includes Discussion Questions

Pope Francis

Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division

Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.

Huntington, IN 46750

Encyclical Letter copyright 2015 Libreria Editrice Vaticana Vatican City

Discussion Questions copyright 2015 Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division

20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts for critical reviews, no part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever without permission from the publisher. For more information, visit: www.osv.com/permissions

ISBN: 978-1-61278-386-4 (Inventory No. T1753)

eISBN: 978-1-61278-387-1

LCCN: 2015944355

Cover design: Tyler Ottinger

Cover art: Shutterstock; Good Shepherd mosaic from Mausoleum of

Galla Placidia in Ravenna, Italy

Interior design: Amanda Falk

P RINTED IN THE U NITED S TATES OF A MERICA

Table of Contents

2. This sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will. The violence present in our hearts, wounded by sin, is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life. This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor; she groans in travail (Rom 8:22). We have forgotten that we ourselves are dust of the earth (cf. Gen 2:7); our very bodies are made up of her elements, we breathe her air and we receive life and refreshment from her waters.

Nothing in this world is indifferent to us

3. More than fifty years ago, with the world teetering on the brink of nuclear crisis, Pope Saint John XXIII wrote an Encyclical which not only rejected war but offered a proposal for peace. He addressed his message Pacem in Terris to the entire Catholic world and indeed to all men and women of good will. Now, faced as we are with global environmental deterioration, I wish to address every person living on this planet. In my Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, I wrote to all the members of the Church with the aim of encouraging ongoing missionary renewal. In this Encyclical, I would like to enter into dialogue with all people about our common home.

4. In 1971, eight years after Pacem in Terris, Blessed Pope Paul VI referred to the ecological concern as a tragic consequence of unchecked human activity: Due to an ill-considered exploitation of nature, humanity runs the risk of destroying it and becoming in turn a victim of this degradation.

He spoke in similar terms to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations about the potential for an ecological catastrophe under the effective explosion of industrial civilization, and stressed the urgent need for a radical change in the conduct of humanity, inasmuch as the most extraordinary scientific advances, the most amazing technical abilities, the most astonishing economic growth, unless they are accompanied by authentic social and moral progress, will definitively turn against man.

5. Saint John Paul II became increasingly concerned about this issue. In his first Encyclical he warned that human beings frequently seem to see no other meaning in their natural environment than what serves for immediate use and consumption.

6. My predecessor Benedict XVI likewise proposed eliminating the structural causes of the dysfunctions of the world economy and correcting models of growth which have proved incapable of ensuring respect for the environment.

United by the same concern

7. These statements of the Popes echo the reflections of numerous scientists, philosophers, theologians and civic groups, all of which have enriched the Churchs thinking on these questions. Outside the Catholic Church, other Churches and Christian communities and other religions as well have expressed deep concern and offered valuable reflections on issues which all of us find disturbing. To give just one striking example, I would mention the statements made by the beloved Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, with whom we share the hope of full ecclesial communion.

8. Patriarch Bartholomew has spoken in particular of the need for each of us to repent of the ways we have harmed the planet, for inasmuch as we all generate small ecological damage, we are called to acknowledge our contribution, smaller or greater, to the disfigurement and destruction of creation.

9. At the same time, Bartholomew has drawn attention to the ethical and spiritual roots of environmental problems, which require that we look for solutions not only in technology but in a change of humanity; otherwise we would be dealing merely with symptoms. He asks us to replace consumption with sacrifice, greed with generosity, wastefulness with a spirit of sharing, an asceticism which entails learning to give, and not simply to give up. It is a way of loving, of moving gradually away from what I want to what Gods world needs. It is liberation from fear, greed and compulsion.

Saint Francis of Assisi

10. I do not want to write this Encyclical without turning to that attractive and compelling figure, whose name I took as my guide and inspiration when I was elected Bishop of Rome. I believe that Saint Francis is the example par excellence of care for the vulnerable and of an integral ecology lived out joyfully and authentically. He is the patron saint of all who study and work in the area of ecology, and he is also much loved by non-Christians. He was particularly concerned for Gods creation and for the poor and outcast. He loved, and was deeply loved for his joy, his generous self-giving, his openheartedness. He was a mystic and a pilgrim who lived in simplicity and in wonderful harmony with God, with others, with nature and with himself. He shows us just how inseparable the bond is between concern for nature, justice for the poor, commitment to society, and interior peace.

11. Francis helps us to see that an integral ecology calls for openness to categories which transcend the language of mathematics and biology, and take us to the heart of what it is to be human. Just as happens when we fall in love with someone, whenever he would gaze at the sun, the moon or the smallest of animals, he burst into song, drawing all other creatures into his praise. He communed with all creation, even preaching to the flowers, inviting them to praise the Lord, just as if they were endowed with reason. Such a conviction cannot be written off as naive romanticism, for it affects the choices which determine our behavior. If we approach nature and the environment without this openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs. By contrast, if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously. The poverty and austerity of Saint Francis were no mere veneer of asceticism, but something much more radical: a refusal to turn reality into an object simply to be used and controlled.

12. What is more, Saint Francis, faithful to Scripture, invites us to see nature as a magnificent book in which God speaks to us and grants us a glimpse of his infinite beauty and goodness. Through the greatness and the beauty of creatures one comes to know by analogy their maker (

Next page