And His disciples answered Him: from

whence can anyone fill them here

with bread in the wilderness?

MARK, 8:4

To Jean Danielou, S.J.

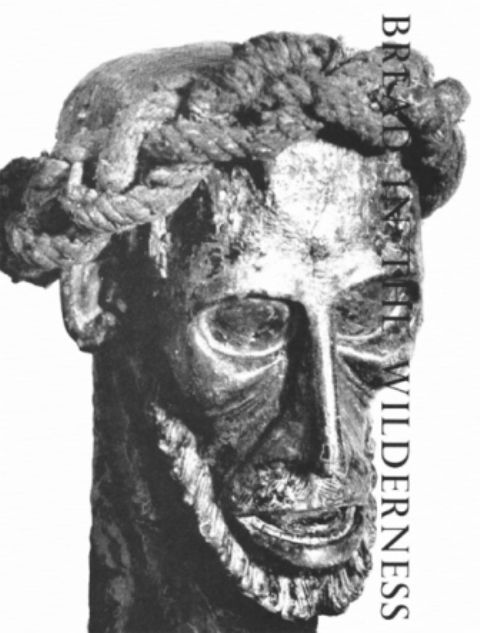

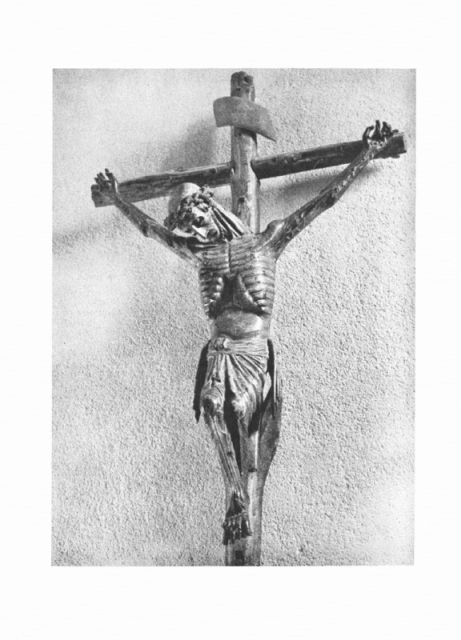

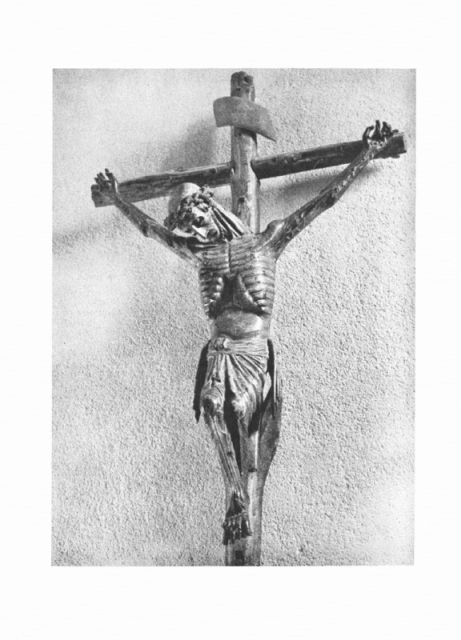

The pictures in this book are of a famous Crucifix, venerated for centuries in a chapel adjoining the Cathedral of Perpignan, in Southern France. Nobody knows who carved this terrible masterpiece. No one is quite sure where it came from. Was it brought to Perpignan from Germany or Spain? Or was it, as most people believe, the work of an anonymous Catalan, living in Perpignan or in the nearby Pyrenees? Whatever may be the origin of the Devot Christ, there has probably never been a work of Christian art that so powerfully expressed the suffering of Christ on the Cross. This is indeed the Christ Whom the prophet Isaias described as a twisted root laid bare to the sun on the parched rocks of the desert. This is truly the Christ of whom Isaias cried: There is no beauty in Him nor comeliness: and we have seen Him and there was no sightliness that we should be desirous if Him, despised and the most abject of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with infirmity: Surely He hath borne our infirmities and carried our sorrows, and we have thought Him as it were a leper, and one struck by God and afflicted. This too is the Christ of the twenty-first Psalm and of the other Psalms we discuss in this book. It is the Christ of the Dark Night of St John of the Cross. It is the Christ Who shares His agony with the mystics. And finally it is the Christ of our own timethe Christ of the bombed city and of the concentration camp. We have seen Him and we know Him well. This Devot Christ is the image of what the men of our time are doing to one another for they are murdering Him in one another. But because there are many in whom He dies again, there are also many in whom He lives again, for Christ dies only in order to rise again from the dead. This picture, therefore is the picture of our Redeemer, the Saviour of the World. Of Him Isaias said, in the same fifty-third chapter of his prophecy: He was wounded for our iniquities, He was bruised for our sins; the chastisement of our peace was upon Him, and by His bruises we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray, every one hath turned aside into his own way: and the Lord hath laid upon Him the iniquity of us all.

Small wonder that this Devot Christ is sought out day by day by penitents and pilgrims in the French Catalan country. This Crucifix is held to be miraculous, to grant many favors to those possessed of pure devotion ab los que tenan pura devocio. And there is a legend about Him. The bowed head is said to fall, each year, a fraction of an inch toward the chest. The Catalans say that when the chin finally comes to rest upon the chest, it will be the end of our world.

PROLOGUE:

What is this book about? For whom is it written?

It is a book about the Psalms. The Psalms are perhaps the most significant and influential collection of religious poems ever written. They sum up the whole theology of the Old Testament. They have been used for centuries as the foundation for Jewish and Christian liturgical prayer. They still play a more important part than any other body of religious texts, in the public prayer of the Church. Benedictine and Cistercian monks chant their way through the entire Psalter, once a week. Those whose vocation in the Church is prayer find that they live on the Psalmsfor the Psalms enter into every department of their life. Monks get up to chant Psalms in the middle of the night. They find phrases from the Psalter on their lips at Mass. They interrupt their work in the fields or the workshops of the monastery to sing the Psalms of the day hours. They recite Psalms after their meals and practically the last words on their lips at night are verses written hundreds of years ago by one of the Psalmists.

For the monk who really enters into the full meaning of his vocation, the Psalms are the nourishment of his interior life and form the material of his meditations and of his own personal prayer, so that at last he comes to live them and experience them as if they were his own songs, his own prayers.

This would not be possible if the Psalms were nothing more than literature to those who have to pray them every day. Art and literature as such no doubt have a part to play in the monastic life. But when a man lives in the naked depths of an impoverished spirit, face to face with nothing but spiritual realities for year after year, art and literature can come to seem peculiarly shabby and unsubstantialor else they become a lure and a temptation. In either case, they are a potential source of unrest and of dissatisfaction.

Yet the liturgical prayer of the monk is one of the great pacifying influences in a life that is all devoted to serenity and interior peace. There is only one explanation for this. The Psalms acquire, for those who know how to enter into them, a surprising depth, a marvelous and inexhaustible actuality. They are bread, miraculously provided by Christ, to feed those who have followed Him into the wilderness. I use this symbol advisedly. The miracle of the multiplication of the loaves usually suggests the Sacrament of the Eucharist, which it foreshadowed: but the reality which nourishes us in the Psalms is the same reality which nourishes us in the Eucharist, though in a far different form. In either case, we are fed by the Word of God. In the Blessed Sacrament, His flesh is food indeed. In the Scriptures, the Word is incarnate not in flesh but in human words. But man lives by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.

This book is not a systematic treatise, but only a collection of personal notes on the Psalter. They are the notes of a monk, written in the monastic tradition, and one supposes that they might appeal above all to monks. But in this mysterious age, there is no telling whom the book may reachalthough no one expects it to reach everybody. Perhaps, by its very nature, the book should pretend to address itself to those who do not quite understand why they are obliged, by reason of their vocation, to make the Psalms the substance of their prayer. In any case these pages attempt to put forth a few reasons why the Psalms in spite of their antiquity ought to be considered one of the most valid forms of prayer for men of all time. As for those readers who can only regard the Psalms as literaturethis book will at least offer them some of the reasons why the Psalter seems to be more than literature to those of us who have made it our bread in the wilderness.

1: