ReFormations

MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN

Series Editors:

David Aers, Sarah Beckwith, and James Simpson

Transforming Work

EARLY MODERN PASTORAL AND LATE MEDIEVAL POETRY

KATHERINE C. LITTLE

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

Copyright 2013 by University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

All Rights Reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-268-08570-4

This eBook was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

CONTENTS

This book has been a pleasure to write not least because of all the opportunities it has given me to learn from colleagues, students, and friends. In charting the continuities and disruptions between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, I am indebted to the groundbreaking work of David Aers, Sarah Beckwith, and James Simpson. I thank them for inviting this book into their series, for their comments on my work, and for their advice and encouragement throughout the long process by which this book came into being. Particular thanks are due to David Aers for his remarkable generosity and candor and for providing a salutary example of how to break free of dominant critical narratives.

I have written this book with specific conversations in mind: with early modernists, with theorists of pastoral, with Langlandians. I have benefited a great deal, therefore, from the responses of various audiences. I would like to thank Nigel Smith and Lynn Staley, who read a version of chapter 4 in manuscript. Thank you also to audiences at the Group for Early Modern Cultural Studies in Chicago (GEMCS) (2007); the Harvard Doctoral Conference (2007); the International Langland Conference in Philadelphia (2007); and Spenser at Kalamazoo (2008) for their thought-provoking responses. I am particularly grateful to James Simpson and his colleagues for inviting me to speak at Harvard and to Chi-ming Yang, Kim Hall, and Maureen Quilligan, my fellow panel participants, for stimulating discussion leading up to and at GEMCS.

I owe a great debt of gratitude to my former colleagues and students at Fordham University, where most of this project was completed. The idea for this study emerged out of several undergraduate and graduate courses on medieval romance that I taught there, and I thank my students for their curiosity. Comments from Jocelyn Wogan-Browne and Mary Bly in the early stages helped shape my thinking, and I thank them for their advice. On a more practical note, I am grateful to Nicola Pitchford and Eva Badowska, fabulous former chairs of Fordhams English Department, who helped me negotiate maternity leaves and research leaves, and to Heather Blatt for research assistance. I would also like to thank Mary Erler, Maryanne Kowaleski, and Nina Rowe, all of whom encouraged me in various ways as I pursued my work and helped make Fordham a very happy place to be. Thank you to my new colleagues at the University of Colorado, Boulder, especially William Kuskin, for their warm welcome.

One of my last, though not least, intellectual debts is to Annabel Patterson and her seminar on Sidney and Spenser that I took a very long time ago. I thank her for teaching me some of the rigor and delight with which she approached Spensers poetry.

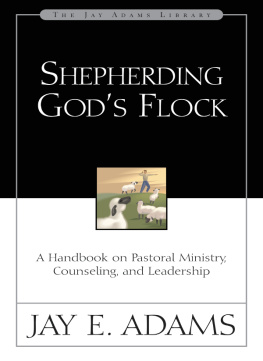

I would like to thank the two readers for University of Notre Dame Press, anonymous and Kellie Robertson, for the time and care they took in providing detailed and helpful comments. Thank you to Barbara Hanrahan, the former editor, and to Stephen Little, the present editor, for guiding me through the stages of publication, and, finally, to Rebecca DeBoer and Christina Lovely. I would also like to thank Wendy McMillen for her work on the cover and James Simpson for suggesting the image.

Generous financial support was provided by a Fordham Faculty Fellowship and a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and I am deeply grateful for the time these grants afforded me for research and writing.

I could not have written this book without the loving support of my friends and family. Anna Katsnelson and Eric Rosenbaum were delightful companions whether in Texas or New York. Jennifer Bosson and Katrine Bangsgaard provided much-needed laughs and breaks from the solitary work of writing. Thank you to Paul Neimann and Diane Neimann for their generosity and good humor and for offering respite at their idyllic lakeside cabin. Thank you to my father, Silas Little, for his love and support, and to my mother, Mary Ann Beverly, who has encouraged me in every one of my pursuits. Finally, it would be difficult to describe the gratitude I feel toward my family. To Paul for being the staunchest of allies, for listening to every word, and for holding on to what is fun and funny amidst all of the hard work, and to Charlotte and Daisy, for being never-ending sources of delight: all of you remind me every day of how lucky I am.

An earlier version of chapter 4 appeared as Transforming Work: Protestantism and the Piers Plowman Tradition, in the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 40 (2010): 497526, and some material from chapters 1 and 5 previously appeared as The Other Past of Pastoral: Langlands Piers Plowman and Spensers Shepheardes Calender, in Exemplaria 21 (2009): 16179. I thank the editors at Duke University Press and Maney Publishing for permission to reproduce the work here.

T he divide between the medieval and the early modern (or Renaissance) periods is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in studies of the pastoral mode, in which the literature of the Middle Ages is often entirely absent. Either these studies begin with the sixteenth-century pastoral of Edmund Spensers Shepheardes Calender or William Shakespeares plays, or they begin with the eclogues of Theocritus (or Virgil) and then skip the Middle Ages entirely to focus, once again, on sixteenth-century texts. For Montrose, the only history that matters is that of immediate contextthat is, the social and political world of the Elizabethan court. Despite the wide range of approaches to pastoral, then, all of the studies implicitly reinforce a very traditional periodization: a clean break between the Middle Ages and the early modern period.

At first glance, the neglect of medieval literature in the study of pastoral makes perfect sense. It is relatively easy to argue that there

The absence of a medieval pastoral that is continuous with the early modern period does not mean, however, the absence of any medieval influences on early modern pastoral; perhaps the question has been posed the wrong way thus far. Instead of assuming that the first writers of pastoral understood it exclusively by means of Virgil and Mantuan because that is how we, as later readers, understand it, we could try to recover the specificity of these first encounters with the pastoral mode, encounters that were surely influenced by a knowledge of medieval literature as well. After all, on closer look, the first eclogues to appear in sixteenth-century England look backward to a pre-pastoral medieval period as well as forward to a mode that is recognizably pastoral: these are the eclogues of Alexander Barclay (composed ca. 151314; printed in 1548 and 1570), Barnabe Googe (1563), and Edmund Spenser (1579), whose eclogues are otherwise known as the Shepheardes Calender. While all of these texts certainly invoke the new pastoral, either of Virgil directly or of Virgil by way of Mantuan, they contain traces of what one can only call medieval literary traditions. Indeed, the editors of the two earliest eclogue collections, by Barclay and Googe, call these texts medieval, and even Spensers editor, who insists on the novelty of the

Next page