Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, Professor of the History of Modern Civilization at the Collge de France, Paris, is one of his countrys leading historians. He has held posts at the universities of Princeton and Michigan, and has been an editor of the journal Annales since 1967. His books include The Territory of the Historian, The Peasants of Languedoc, Montaillou (Penguin 1980), Carnival in Romans: A Peoples Uprising in Romans 15791580 (Penguin 1981), Love, Death and Money in the Pays dOc (Penguin 1984) and Jasmins Witch (Penguin 1990).

Introduction

This introduction was specially written for the English edition of Montaillou, which is a shorter version of the French.

Though there are extensive historical studies concerning peasant communities there is very little material available that can be considered the direct testimony of peasants themselves. It is for this reason that the Inquisition Register of Jacques Fournier, Bishop of Pamiers in Arige in the Comt de Foix (now southern France) from 1318 to 1325, is of such exceptional interest. As a zealous churchman he was later to become Pope at Avignon under the name Benedict XII he supervised a rigorous Inquisition in his diocese and, what is more important, saw to it that the depositions made to the Inquisition courts were meticulously recorded. In the process of revealing their position on official Catholicism, the peasants examined by Fourniers Inquisition, many from the village of Montaillou, have given an extraordinarily detailed and vivid picture of their everyday life.

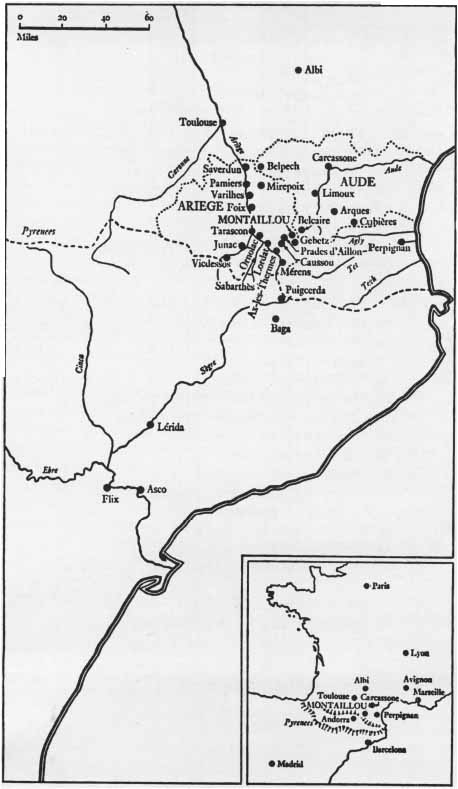

Montaillou is a little village, now French, situated in the Pyrenees in the south of the present-day department of Arige, close to the frontier between France and Spain. The department of Arige itself corresponds to the territory of the diocese of Pamiers, and to the old medieval Comt de Foix, once an independent principality. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the principality, ruled over by the important family of the Comtes de Foix, became a satellite of the powerful kingdom of France. The large province of Languedoc, adjacent to Arige, was already a French possession.

Montaillou was the last village which actively supported the Cathar heresy, also known as Albigensianism, after the town of Albi, in which some of the heretics lived. It had been one of the chief heresies of the Middle Ages, but after it had finally been wiped out in Montaillou between 1318 and 1324 it disappeared completely from French territory. It appeared in the twelfth or thirteenth centuries in Languedoc in northern Italy, and, in slightly different forms, in the Balkans. Catharism is not to be confused with Waldensianism, another heretical sect which originated in Lyons but which hardly affected Arige. Catharism may have been based on distant Oriental or Manichaean influences, but this is only hypothesis. However, we do know a great deal about the doctrine and rites of Catharism in Languedoc and northern Italy.

Catharism or Albigensianism was a Christian heresy: there is no doubt on this point at least. Its supporters considered and proclaimed themselves true Christians, good Christians, as distinct from the official Catholic Church which according to them had betrayed the genuine doctrine of the Apostles. At the same time, Catharism stood at some distance from traditional Christian doctrine, which was monotheist. Catharism accepted the (Manichaean) existence of two opposite principles, if not of two deities, one of good and the other of evil. One was God, the other Satan. On the one hand was light, on the other dark. On one side was the spiritual world, which was good, and on the other the terrestrial world, which was carnal, physical, corrupt. It was this essentially spiritual insistence on purity, in relation to a world totally evil and diabolical, which gave rise retrospectively to a probably false etymology of the word Cathar, which has been said to derive from a Greek work meaning pure. In fact Cathar comes from a German word the meaning of which has nothing to do with purity. The dualism good/evil or God/Satan subdivided into two tendencies, according to region. On the one hand there was absolute dualism, typical of Catharism in Languedoc in the twelfth century: this proclaimed the eternal opposition between the two principles, good and evil. On the other hand was the modified dualism characteristic of Italian Catharism: here God occupies a place which was more eminent and more eternal than that of the Devil.

Catharism was based on a distinction between a pure lite on the one hand (perfecti, parfaits, bonshommes or hrtiques), and on the other hand, the mass of simple believers (credentes). The parfaits came into their illustrious title after they had been initiated by receiving the Albigensian sacrament of baptism by book and words (not by water). In Cathar language, this sacrament was called the consolamentum (consolation). Ordinary people referred to it as heretication. Once he had been hereticated a parfait had to remain pure, abstaining from meat and women. (Catharism, though not entirely anti-feminine, showed no great tolerance of women.) A parfait had the power to bless bread and to receive from ordinary believers the melioramentum or ritual salutation or adoration. He gave them his blessing and kiss of peace (caretas). Ordinary believers did not receive the consolamentum until just before death, when it was plain that the end was near. This arrangement allowed ordinary believers to lead a fairly agreeable life, not too strict from the moral point of view, until their end approached. But once they were hereticated, all was changed. Then they had to embark (at least in the late Catharism of the 1300s) on a state of endura or total and suicidal fasting. From that moment on there was no escape, physically, though they were sure to save their souls. They could touch neither women nor meat in the period until death supervened, either through natural causes or as a result of the endura.

Around 1200, Catharism had partly infected quite large areas of Languedoc, which at that period did not yet belong to the kingdom of France. Such a state of affairs could not be allowed to continue. In 1209 the barons of the north of France organized a crusade against the Albigensians. The armies marched southwards in answer to an appeal from the Pope. Despite the death in 1218 of Simon de Montfort, the brutal leader of the northern crusaders, the King of France gradually extended his power over the south and took advantage of the pretext offered by the heretics to annex Languedoc