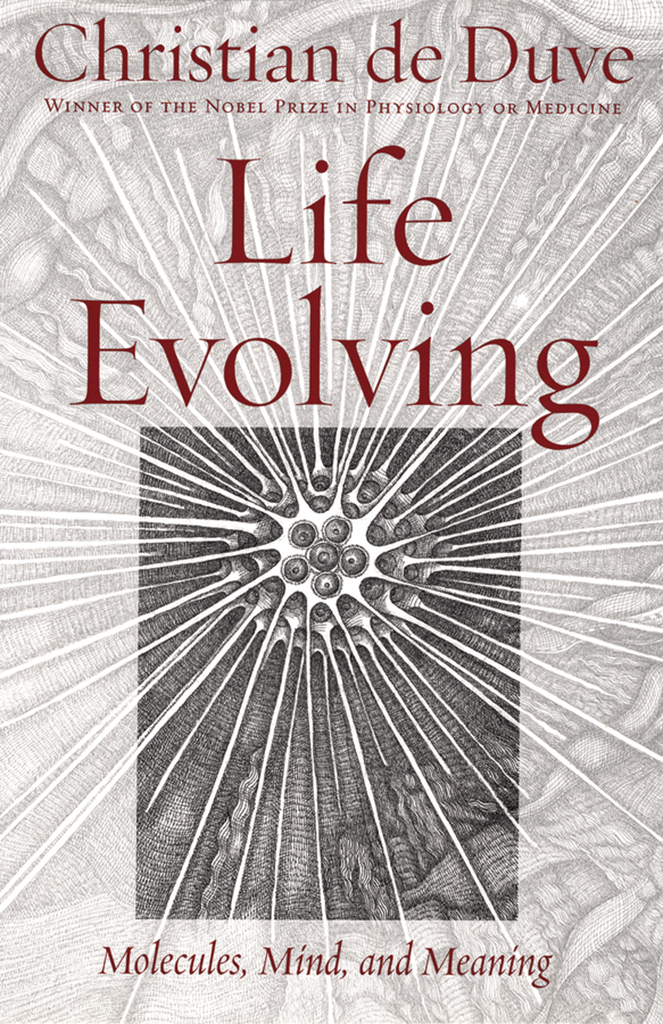

Life Evolving

Molecules, Mind, and Meaning

Christian de Duve

2002

OxfordNew York

AucklandBangkokBuenosAiresCape TownChennai

Dar es SalaamDelhiHong KongIstanbulKarachiKolkata

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityMumbaiNairobi

So PauloShanghaiSingaporeTaipeiTokyoToronto

and an associated company in Berlin

Copyright 2002 by The Christian Ren de Duve Trust

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

De Duve, Christian.

Life evolving : molecules, mind, and meaning / Christian de Duve.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-19-515605-6

1. LifeOrigin.2. Evolution (Biology)3. Life (Biology)I. Title.

QH325 .D415 20002

576. 88dc21 2002075407

Permission for the reproduction of the images that appear in this book

was kindly granted by the artist, Ippy Patterson. The copyright

for these images rests with the artist.

C ONTENTS

This preface is dedicated to all my colleagues,

past and present, at the Catholic University of Louvain

A WHIFF OF WOOD SMOKE

On a clear summer night almost 75 years ago, I was sitting, wrapped in a blanket, a scarf on my head, with a group of similarly clad youngsters circling a campfire. There was not a breath of wind. The flames rose straight toward an inky sky studded with stars. So did our voices joined in song, the only sound, with occasional crackling of burning wood, to break the silence of the night. All of a sudden, for a brief instant, light fused with darkness, song and silence became one, and I felt carried to another world, seized by intense emotion, suffused with a sense of unfathomable mystery, feeling, beyond the infinite depths of space, the awesome majesty of God.

Today, the boy scout of my reminiscence is an old man. What was then his future is now my past, a past that happened to coincide with the most dramatic burst of knowledge in the whole history of humankind. The night sky of my youth has been explored to the outermost distance and earliest beginnings of the universe. The innumerable appearances of matter have been reduced to a small set of elementary particles and forces. Life itself has yielded its secrets. Its central mechanisms have been unravelled in intimate detail, and its history, which, as we now know, includes that of humankind, has been probed back to an origin lost in the mists of time.

As chance would have it, I did not live through those momentous events merely as a passive spectator. I was a privileged inside witness to them and even, to a modest extent, an active participant. This dizzying adventure was also a revealing discovery of reality, which totally upset the nave set of beliefs from which had sprung the romantic mysticism of my childhood. Yet memory of that summer night never entirely faded away. It needs only a whiff of wood smoke to bring back the feeling of fervor and wonder that filled me at the time. The magic has gone, but not the sense of mystery.

EARLY INFLUENCES

I have recalled this childhood experience because it helps explain the tenor of this book, greatly influenced by my family background and early upbringing, especially in the religious domain. My family was Catholic, more by tradition and social conformism than by deep-felt conviction. We believed, without asking why, as a matter of course. Observance was faithful but largely perfunctory. We scrupulously refrained from eating meat on Fridays, attended mass every Sunday, confessed our sins regularlyor, in the case of the more tepid, at least once a year at Easter time, as prelude to the obligatory yearly Communion known as ones Easter dutyand we took care not to eat any solid food a minimum of twelve hours before receiving the sacred host at Communion. Religious holidays, such as Christmas or Easter, were duly celebrated. Church ceremonies underlined all major family events. We were baptized soon after birth and, later, when we had grown old enough to understand what was going on, confirmed by the local bishop, who took the trouble to come personally on that occasion. We married in church, which was also our last stop on the way to our final resting place.

Religion itself, however, hardly entered our home, except for the presence of a crucifix or other sacred image in every room. We never prayed together, read devout literature, or talked about religious topics. Politically, my father was mildly anticlerical and always voted liberal, not Catholic (the name of a political party at the time). I myself learned early, from spending holidays with German relatives who were Lutherans and with English friends of my parents who were nominally Anglicans but hardly bothered with religious practice, that one could reject the authority of the pope and skip mass on Sundays and still escape eternal damnationthat, at least, is what I believedif one led a decent life. Rumor had it that some family members were actually unbelievers, perhaps evenperish the thoughtFreemasons!

This broad-minded and tolerant family atmosphere did not prevent me from taking religion very seriously. In the Jesuit school I attended, Catholic doctrine was strictly imposed by highly intelligent and cultured Fathers, who described it as an unassailable, rational construction, firmly based on the teachings of Aristotle, as revised by Thomas Aquinas. Science, on the other hand, was poorly taught by teachers who distrusted it and took care not to present it as an opening to understanding the world. Only mathematics, thanks to its abstract character, escaped this neglect and was well expounded. Not knowing any better and not being inclined to question the wisdom of my teachers, I found this combination of reason and faith intellectually satisfactory and even appealing.

At the end of my humanities, as classical high-school studies were called, there was never a moment of doubt in my mind or anyone elses that I should enter the Catholic University of Louvain, steering clear of its nearby rival the godless Free University of Brussels, founded in 1834 by a group of wealthy Freemasons with the aim of promoting, in direct opposition to dogmatic Louvain, a pernicious doctrine of free thinking. In spite of my love for the classics, I opted for medical studies, mainly because I was attracted by the popular man in white image of the physician in the service of suffering humanity.

Through a combination of circumstances that have no place in this account, I discovered scientific research as a medical student and became so enamored with it that I abandoned clinical practice and specialized in biochemistry. At that same time, thanks to my first mentor, professor Joseph Bouckaert, to whom I remain deeply indebted, I discovered the scientific method of seeking truth, not by rational deduction from an a priori statement presented as incontrovertible, but by observation and experiment, continually questioned and subjected to the rigorous criterion of objective verification. It was an illumination that swept away, as by a tidal wave, the scholastic approach of the Jesuits and severely shook its doctrinal foundation. Claude Bernard replaced Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas as my intellectual guide.

Next page