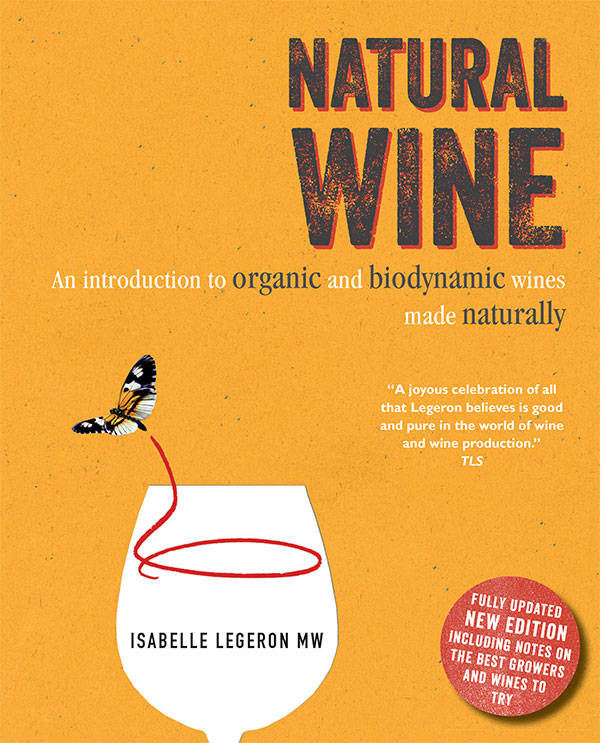

NATURAL

WINE

NATURAL

WINE

an introduction to organic and biodynamic wines

made naturally

ISABELLE LEGERON MW

TO BOAH, FOR MAKING IT HAPPEN

This second edition published in 2017 by CICO Books

An imprint of Ryland Peters & Small Ltd

20-21 Jockeys Fields341 E 116th St

London WC1R 4BWNew York, NY 10029

www.rylandpeters.com

10 98765432

First published in 2014

Text Isabelle Legeron 2017

Design CICO Books 2014

Photography by Gavin Kingcome CICO Books 2014

For additional picture credits, see .

The authors moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 78249 483 6

Printed in China

Editor: Caroline West

Designer: Geoff Borin

Photographer: Gavin Kingcome

Illustrator: Anthony Zinonos

Art director: Sally Powell

Head of production: Patricia Harrington

Publishing manager: Penny Craig

Publisher: Cindy Richards

Note to reader

Where possible, metric and imperial equivalents have been provided (for example, for measurements of distance), except in quoted material. Throughout the book, sulfite levels are given in grams per liter (with 1 liter being the equivalent of approximately 34 US fl. oz).

CONTENTS

W e live in a society where its fashionable to wear farmers boots and the chit-chat de rigueur at the local butchers revolves around how long your meat has been hung. Microbreweries and espresso bars populate our urban landscapes, and yet, even against this new agro-chic backdrop, we still, without the slightest thought, wash down our outdoor-reared sausages with the vinous equivalent of a battery chicken. Perhaps this is because, while its become routine to look at the list of ingredients on the back of most foodstuffs, with wine, we cant, as no such labeling laws exist.

This book isnt meant to be an expos of the wine world. Rather, it is a tribute to those wines that are not only farmed well, but also fly in the face of modern winemaking practices, remaining natural against all the odds. It is also a celebration of the remarkable people who create them. Like sailors going to sea, playing the winds and riding the waves, these winemakers understand that nature is much greater than themselves. They acknowledge that not only is it futile, but actually counterproductive, to try to control or tame her, as her magic lies in her power.

I am not a winemaker, nor do I pretend to know everything about the science of winemaking. However, I have an overall vision based on discussions with growers, as well as tasting and drinking thousands of wines. I always intended this book as a starting-point, an invitation to people to explore and begin asking their own questions. My personal views are clear and I dont sit on the fence. Apart from the fact that I genuinely believe all wine should be farmed organically as a bare minimum, there is no political or economic agenda behind the writing. Instead, my opinions are guided by what I enjoy drinking. I believe wines made naturally, with no (or very few) sulfites, taste the best, and this is why I drink nothing else. It is with this in mind that I wrote the book.

Natural Wine is therefore a subjective look at what makes great wine, because, for me, only natural wine can be truly great. I have tried to tell as much of the story as possible through the voices and stories of others, because this world is not my creation. It is real, it exists, and many of the thoughts and experiences I share are those of a much larger community. While doing my research, I found that theres very little written information on the subject, not least because most of the conventional wine world disregards the natural as not commercially viable. Consequently, my findings are largely based on primary research: conversations, interviews, and, of course, a lot of wine tasting.

Wine is something we ingest. Like other types of food, it can be more or less wholesome, more or less manipulated, and more or less delicious. In many ways, this book could easily apply to other foodstuffs, including bread, beer, and milk, that have suffered a similar over-commercialized fate (and natural revival); its just that wine has been a little slow off the mark. So, if you understand how proper food can provide a nourishment that goes beyond merely satisfying hunger and that the energy, commitment, and intentions of natural wine producers matter, then youll see just how special fine, natural wine isand I hope you will never look back.

ISABELLE LEGERON MW

I recently spent a weekend with friends in a beautiful country house in Cornwall. As I watched the fields roll, wave-like, in the sea winds, it dawned on me that this idyllic setting was anything but. For miles, all I could see were cornfields growing on rock-hard, barren earth; not a single other plant was growing amid the green stalks. It was both shocking and extraordinary to see how, in an instant, the same gentle landscape could suddenly seem different, stark, and lifeless.

Nowadays, agricultural monoculture is so prevalent that we dont even notice it. From our neatly trimmed, dandelion-banished, perfect-green lawns to the vast expanses of cereals, sugar beet, and even grapes that blanket our countryside, we like to have nature under control. Where before you might have seen small pockets of pastureland, woodland, and crop fields, carved up by hedgerows that acted as wildlife motorways, today views are dominated by monotony. Since 1950 the number of farms in the United States, for example, has halved, while the average size of those remaining has doubled, so that today only two percent of the countrys farms produce 70 percent of its vegetables.

Monoculture galore in California: miles of grapes and more grapes.

The 20th century changed the face of agriculture. It streamlined, mechanized, and simplified farming in an attempt to increase yields and maximize short-term profits. This industrialization became known as the Green Revolution. We call it intensification, but it was intensification per farmer, not per square meter, explain agronomists Claude and Lydia Bourguignon. In North America, yes, a single farmer can manage 500 hectares alone, but the traditional agro-silvo-pastoral farming system was actually far more productive per square meter.

Grape-growing, like the rest of agriculture, is no exception. Traditionally, in Italy, vines were very biodiverse, explains Stefano Bellotti, a natural grower in Piedmont. They grew alongside trees or vegetables, and growers also cultivated wheat, beans, chickpeas, and even fruit trees, between the rows. Biodiversity was very important.