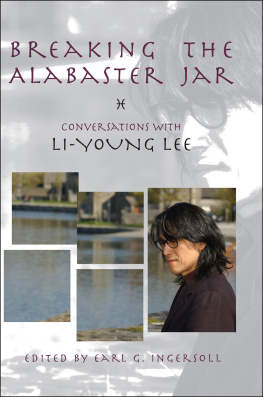

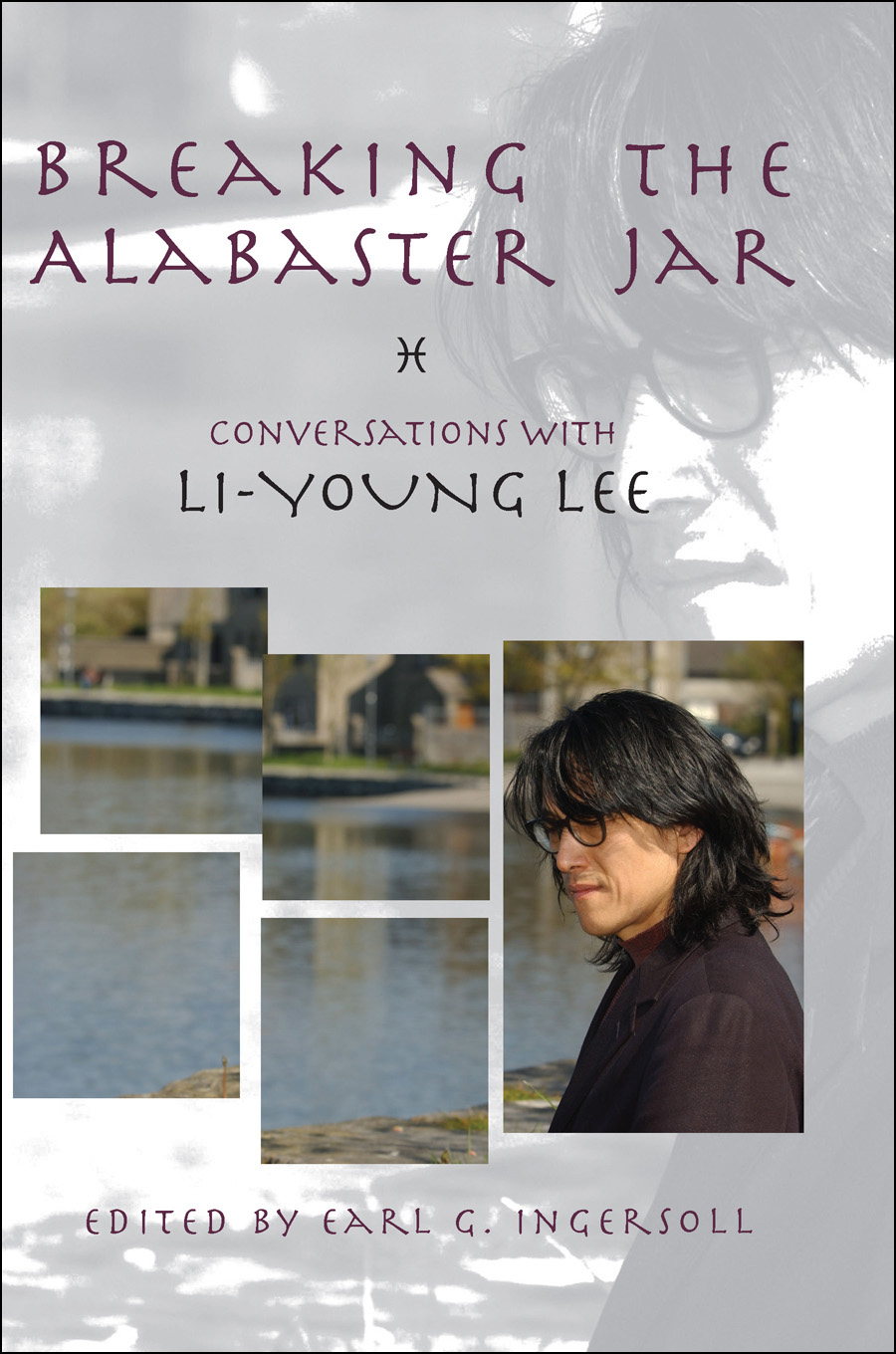

Breaking the Alabaster Jar:

Conversations with Li-Young Lee

The printing of this book was made possible, in part, by a generous donation from the Mary S. Mulligan Charitable Trust, and by the generous support of Jane Schuster, whose gift honors the heart-intelligence of BOA poets Anthony Piccione and Li-Young Lee.

Books by Li-Young Lee

Rose. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 1986.

The City in Which I Love You. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 1990.

The Winged Seed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Book of My Nights. Rochester, NY: BOA Editions, 2001.

Copyright 2006 by Earl G. Ingersoll

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition

12 13 14 15 16 6 5 4 3 2

Publications by BOA Editions, Ltd.a not-for-profit corporation under section 501 (c) (3) of the United States Internal Revenue Codeare made possible with the assistance of grants from the Literature Program of the New York State Council on the Arts; the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts; County of Monroe, NY; the Lannan Foundation for support of the Lannan Translation Selection Series; Sonia Raiziss Giop Charitable Foundation; Mary S. Mulligan Charitable Trust; Rochester Area Community Foundation; Arts & Cultural Council for Greater Rochester; Steeple-Jack Fund; Elizabeth F. Cheney Foundation; Chadwick-Loher Foundation in honor of Charles Simic and Ray Gonzalez; Chesonis Family Foundation; Ames-Amzalak Memorial Trust in memory of Henry Ames, Semon Amzalak and Dan Amzalak; and contributions from many individuals nationwide.

For Information about permission to reuse any material from this book please contact The Permissions Company at

See Colophon on for special individual acknowledgments.

Cover Design: Lisa Mauro

Cover Photo: Andrew Downes

Back Cover Artwork: Symbiology by Li-Lin Lee, photo courtesy of Walsh Gallery

Interior Design and Composition: Richard Foerster

Manufacturing: McNaughton & Gunn, Lithographers

BOA Logo: Mirko

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Li-Young, 1957

Breaking the alabaster jar : conversations with Li-Young Lee / edited by Earl G. Ingersoll.1st ed.

p. cm. (BOA Editions American readers series ; no. 7)

ISBN 1929918828 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Lee, Li-Young, 1957Interviews. 2. Poets, American--20th century--Interviews. 3. PoetryAuthorship. I. Ingersoll, Earl G., 1938 II. Title. III. American reader series ; v. 7.

PS3562.E35438Z46 2006

811'.54--dc22 2006004124

| BOA Editions, Ltd. 250 North Goodman Street, Suite 306 Rochester, NY 14607 www.boaeditions.org A. Poulin, Jr., Founder (1938-1996) |

|

Breaking the Alabaster Jar

Introduction

One place to begin this collection of interviews with Li-Young Lee is the inevitable question he is asked by interviewers: Where are you from? Occasionally when he is in a playful mood, he answers, Chicago, deflecting the interviewers obvious efforts to engage the poet in a discussion of his identity as an Asian American. If compelled to confront questions of his ethnicity, he stresses very forcefully that although he was born in Indonesia he rejects any effort to label him Indonesian, since Indonesia under Sukarno imprisoned and tortured his father shortly after Lee was born. Lee spent his early childhood there and has fond memories of an Indonesian nanny whom he attempted unsuccessfully to locate when he returned to Indonesia as a young adult. As he strongly emphasizes, however, his parents were ethnic Chinese, who felt forced to emigrate from China as they had struggled to find their place in their homeland after it became Communist in 1948. When Lee visited China it was not a Homeland for him. One of the palatial homes his mothers family lived in when she was a child had been converted into a hospital, and the familys lands had become public parks. During the Cultural Revolution the bones of his mothers family were dug up and scattered about. Even Lees brother who died in China after the family emigrated appears to have been buried in a mass grave. And yet Lee obviously continues to have ties to Chinese culture; for example, he speaks to his mother in Chinese, her only language, not in English, his second language after Mandarin Chinese. On the other hand, his first poem was in English and he has not written in Chinese. Because those who know Lees poems, but especially the memoir The Winged Seed, are familiar with his comments on his family background and early life, an effort has been made to reduce those elements in the conversations to follow in order to emphasize the provocative remarks Lee makes about the writing of his poems and about his sense of the writers craft.

As he tells interviewers, Lee is well aware that excessive emphasis on his life and especially on his ethnicity can direct attention away from the poems themselves. Clearly the identity of Asian-American poet has the potential of ghettoizing those who might be drawn in by the possibilities of exploiting their ethnicity to advance in a culture intent on marketing writers through their ethnicities. Even more, however, as he indicates again and again, Lee knows how indebted he is to American poets, older poets such as Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, but also more recent poets such as Philip Levine and Gerald Stern. He might well identify himself as Asian-American to the census taker at his door; however, it is as an American poet that he would see himself first and foremost. At the same time, he might be a little hesitant to use that high-powered term poet because he still feels, as recently as the Fox interview, that he has to evolve toward those great poets he so admires: In order to write like Emily Dickinson, for instance, I have to change. As he indicates more than once, when he sits down at the kitchen table at night to write poems, he is not likely to think to himself, Here I am, an Asian American setting out to compose an Asian-American poem. Indeed, in the Cooper and Yu interview he voices this concern with ethnicity very bluntly: When they introduce Philip Levine to do a reading, they dont say, Heres the Jewish-American poet, Philip Levine. They just say the American poet. When they introduce me, they say, Hes the Chinese-American poet. Some of these issues take a less somber course in the conversations. When his sons asked about their ethnicity and he explained that he is ethnic Chinese and their mother Donna is Italian-American, they responded that they were half-Chinese and half-regular. Often his interviewers seem impelled to get him to confirm an identity as a spokesman for the Asian diaspora; they soon discover, however, that he refuses the role of spokesman for anyone or anythingexcept perhaps the supreme worth of art. In seeing himself as an American, he also addresses issues of homelessness to which many Americans can respond, especially as he admits to a sense of displacement, a sense that his home is someplace else.