Copyright page

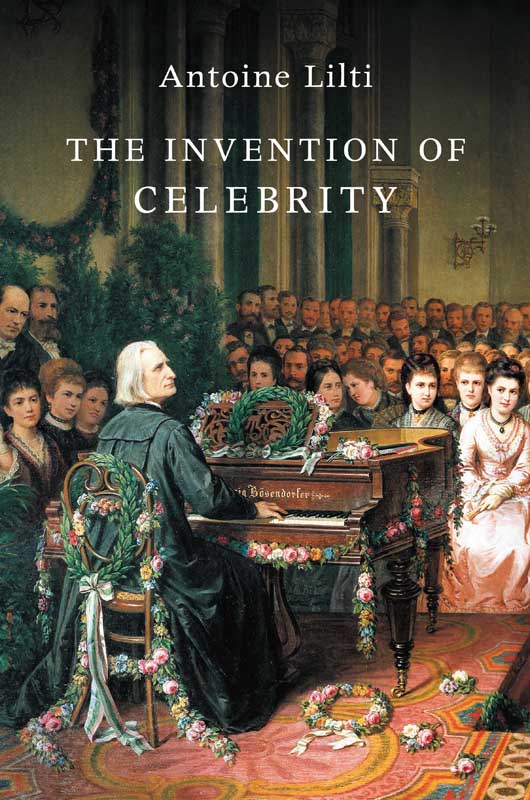

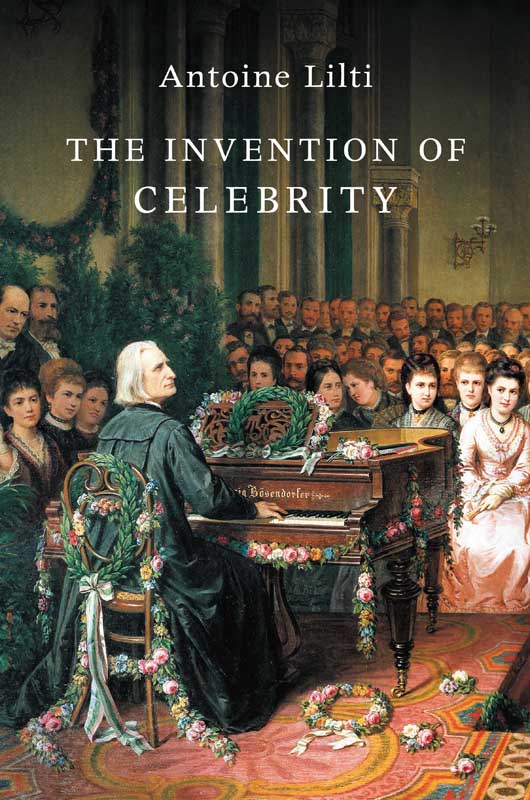

First published in French as Figures publiques. L'invention de la clbrit. 17501850, Librairie Arthme Fayard, 2015

This English edition Polity Press, 2017

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0873-0

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0874-7 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10 on 11.5 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:

politybooks.com

Acknowledgments

This book has been a work in progress for almost ten years, and since its first formulation I have had time to accumulate numerous debts, which I here have the pleasure of acknowledging. Many of my colleagues and friends had the patience to listen to me or read me, discuss my hypotheses, suggest examples or readings. This permanent dialogue that allows one to avoid the stumbling blocks one encounters when working alone is an essential aspect of the constant pleasure I find in doing research.

There were several drafts of this work on celebrity, the first focusing on the issue of Rousseau, and then by progressively enlarging on the questions in several seminars and symposiums. I had the good fortune to be invited to the Maison Franaise d'Oxford and the following universities: Cornell, Johns Hopkins, Berkeley, Stanford, Bordeaux III, Cambridge, Peking, Grenoble, Crteil, Geneva, and Montreal, including several seminars at the cole des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). I want to thank everyone who made these meetings possible as well as all the participants. I owe much, also, to those in my own seminars at the cole Normale Suprieure and then at EHESS who patiently listened to me construct the principal chapters of this book. I must admit I often tested ideas on them first and they sometimes convinced me of their point of view.

Among the many colleagues whom I have the pleasure of thanking, I want to acknowledge Romain Bertrand, Florent Brayard, Caroline Callard, Jean-Luc Chappey, Christophe Charle, Roger Chartier, Yves Citton, Dan Edelstein, Darrin McMahon, Robert Darnton, Pierre-Antoine Fabre, Carla Hesse, Steve Kaplan, Bruno Karsenti, Cyril Lemieux, Tony La Vopa, Rahul Markovits, Renaud Morieux, Robert Morrissey, Ourida Mostefai, Nicolas Offenstadt, Michel Porret, Daniel Roche, Steve Sawyer, Anne Simonin, Cline Spector, and Mlanie Traversier. The following showed great benevolence, or friendship, in reading whole chapters, sometimes even the entire book, and helped me avoid many errors: tienne Anheim, David Bell, Barbara Carnevali, Charlotte Guichard, Jacques Revel, Silvia Sebastiani, Valrie Theis, and StphaneVan Damme. I thank each of them.

From the Canal Saint-Martin to the hill of the Pincio and back again, Charlotte was always there, and this book owes more to her than I can ever say. Juliette and Zo will perhaps read it in a few years, remembering that I was not always available as much as they would have liked. Or maybe not.

I am very glad that my book has now been issued in English, and I would like to heartily thank John Thompson for making this publication possible. Many thanks, too, to the whole editorial team at Polity, especially Paul Young and Justin Dyer. I am grateful, finally, to Lynn Jeffress, who had the patience to translate my French prose into English.

Introduction:

Celebrity and Modernity

Marie-Antoinette is Lady Di! On the set where his daughter Sofia was making her film on the French queen, Francis Ford Coppola was struck by the parallel between the two women's destinies. This comparison is strongly suggested by the anachronistic angle taken by the film: Sofia Coppola presents Marie-Antoinette as a young woman today, torn between her thirst for freedom and the constraints imposed by her royal station.

The film's music, which mixes baroque works, 1980s rock groups, and more recent electronic pieces, deliberately emphasizes this interpretation. After the enigmatic and melancholy young women of The Virgin Suicides and Lost in Translation, Marie-Antoinette at first appears to be a new incarnation of the eternal adolescent girl. Then another theme emerges that Sofia Coppola took up overtly in her following films: celebrities' way of life. Like the actor of Somewhere, holed up in his luxury hotel, where he is dying of boredom but does not envisage leaving, Marie-Antoinette is confronted by the obligations associated with her status as a public figure. She can have anything she wants, except perhaps what she really wants most: to escape the exigencies of court society, which appears as a prefiguration of the society of the spectacle (Guy Debord). One scene in the film shows the young crown princess's astonishment and embarrassment when, having awakened after moving into her quarters at Versailles, she finds herself surrounded by courtiers staring at her like modern paparazzi scrutinize the private lives of celebrities. Rejecting the choice between condemning and rehabilitating the queen, Sofia Coppola presents a futile young woman whose historical role seems to consist in a long series of luxurious parties. Filming Marie-Antoinette's life at Versailles as if she were filming the amusements of Hollywood stars, the director foresees a world in which the royal family is no different from that of show business stars.

In general, historians don't like anachronisms. However, it is worth considering this image of Marie-Antoinette as a celebrity avant la lettre who is forced to live constantly under the eyes of others, deprived of all privacy, hobbled in her quest for authentic communication with her contemporaries. It is true that this parallel leaves out an essential element: the court ceremonial. This ceremonial placed sovereigns under the permanent observation of the courtiers and was very different from the modern mechanisms of celebrity. It was not the result of a vast audience's curiosity about the private life of famous people, but instead fulfilled a political function following from the theory of royal representation. Whereas the culture of celebrity is based on the distinction between an inversion of the private and the public (private life being made public by the media), monarchical representation presupposed their identity. In the time of Louis XIV, the lever du roi was not that of a private individual, but rather that of a wholly public person who incarnated the state. Between the political rituals of monarchical representation and the media and commercial apparatuses of celebrity, a profound change made the former obsolete and the latter possible: the conjoint invention of private life and publicity.

Next page