The Dharma belongs to no one. Teachings about the Dharma come now through one person and now through another. What is contained in this book certainly did not originate with me. It is part of a river that flows through me from my Guru, teachers, parents, past incarnations, and life experiences.

As I read this manuscript, I can feel in the turn of a phrase or an image the intimate presence of my Guru and one or another of my teachers. Their very real contributions to this book are warmly and gratefully acknowledged. May this book serve as an expression of appreciation for their teachings.

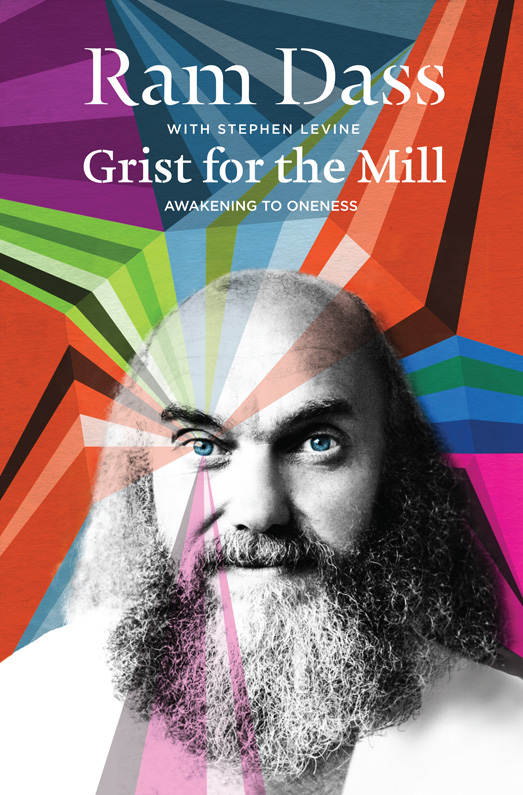

My thanks also to Stephen Levine, co-author, whose sensitive, poetic collaboration made the words come to light as I heard them but could not quite speak them.

Shanti,

Ram Dass

New York City, 1976

Contents

Grist for the Mill came from talks I gave to different groups in the 1970s. It captures those interchanges, but its also about living in the moment, which transcends time. Stephen Levine and I thought these talks would have broad appeal.

The spiritual path is an inner exploration. It exists for anyone at any time who looks within to examine the premise of their own identity or to seek the transcendent reality of the universe. Consciousness is a shared quality of human existence. Except for those rare saintly beings who take birth solely for the benefit of humanity, to teach and inspire, most of us turning on this wheel of birth and death suffer similar afflictions of mind and seductions of the senses.

The astonishing diversity of human nature and individual karma means everyone has their own particular spiritual path and methods that work best for them. Grist for the Mill goes from a general map of the terrain of the spiritual path to answering peoples specific questions.

The primary method we explore uses whatever comes to you in life as food for your spiritual path. At the time I wrote Grist for the Mill, my practice was to see everything that came my way as a manifestation of the Divine Mother who is the energy, or Shakti, of all creation. Around this time I studied with a female teacher named Joya, who for a while represented Shakti for me. I give a chronicle of the ups and downs of that trip here as well.

We Westerners are enthralled with our minds, and I am no exception. I am often the best object lesson for my own teaching. Strategies in the book involve ways to use the mind to go beyond the mind, ways to understand states of consciousness that are beyond thought, and ways to identify ourselves other than through our mind, through our intuition, and so forth. Included are Buddhist ideas about non-self, and how to witness the mind and our attachment to it. Another approach we explore is devotion, or bhakti, in which everything is seen through the lens of love for the Divine.

To understand the sometimes gradual nature of the path, I find it helpful to conceive of a spiritual journey that goes beyond this lifetime. In that view the time factor for souls is an infinity of multiple incarnations, though paradoxically reality lies in being fully present in each moment.

Paradoxes like the infinity of time vs. the timeless present, self vs. non-self, and the need for individual effort vs. surrender to a higher power are all grist for the mill of treading on this pathless path. My Guru, Maharaj-ji, once told me, Enjoy everything! These days I try to simply love everything that comes my way, whether animate or inanimate, pleasant or painful. I hope you too can learn to absorb lifes ecstasies and distresses into your spiritual practice so they are just more grist for the mill.

Namaste,

Ram Dass

Maui, 11 June 2012

The space from which these understandings come has no body, no mouth, it cannot speak. To be communicated, these insights had to cross the wild river of accumulated personality, acculturation, interpretation, opinion, and preference to enter into the limitations of language. They are offered as a near translation of the experience of things as they really are. These teachings were originally offered in the direct, charismatic, air medium of the oral tradition before once again being translated and further grounded into the powerful earth medium of the written word, print on paper, book form.

The transmission from form to form continued without the self-conscious presence of an editor, but instead flowed from the experience out of which these teachings had originated. The continuity was grace elicited from the fullness of each moment as it manifested before us as this book. The collaboration occurred on a plane where the beings collaborating were no one in particular, so there was little to impede or diffuse the natural intensity of the light.

As this oral tradition translated itself into the written word, we decided not to italicize, specialize, the Sanskrit-derived terms such as: sadhana, spiritual practice; karma, the actions of life which breed further reaction; samadhi, deeply concentrated states; Guru, the teacher, the teachingbecause these concepts should not be something different, or other, but should be allowed to enter into the marrow of the language. So too dharma, as natural karmic duty, appropriate action for this incarnation, is not capitalized for it is nothing special, while Dharma, as the truth, Natural Law, the Tao, Gods will, is capitalized to demonstrate its profound universality.

Interwoven from lectures, retreats, articles, and interviews given during 19741976 in Philadelphia, Washington, Lincoln, Seattle, Los Angeles, Boston, Portland, San Francisco, Santa Cruz, Kansas City, and Aspen, and updated for current readers, these words are offered as the gift of the Dharma, which is ever and always present to each of us, in each of us.

Let it shine,

Stephen Levine

Santa Cruz, 1976

In the first half of the seventies, spiritual growth rooted in Eastern mysticism was definitely in. There was a proliferation of spiritual teachers (often self-proclaimed gurus) with sizeable followings. This movement coincided with the psychological growth movement, another significant flowering of that period. Cynics among us referred to these turnings inward as a reflection of narcissism and dubbed the participants the me generation. But it was not just narcissism. In part, these movements represented a healthy balancing after the blood-letting polarization in political action that occurred in our society at the time of the Vietnam conflict.

Though the spiritual groups were often quite flamboyant and smacked of what Trungpa Rinpochea Tibetan Lamareferred to as spiritual materialism, at their root was a genuine yearning to connect with a deeper context from which to lead a life of greater consciousness and equanimity. It was in response to this yearning that this book originally appeared in the mid-seventies.

For the most part, this book is an edited transcript of words spoken at various gatherings during that period. In lecturing, I do not usually follow formally prepared material. Rather, through meditation I empty my mind before speaking, in order that my words might speak from and to those places in the audience and in myself which require that we say again what must still be heard at that moment on our journey.

Now, years later, as I reread this material on the occasion of its republication, I am surprised at how timely the message seems... or perhaps I should say, how outside of time. Perhaps what we need to hear now, just as we needed to hear then, are those eternal verities that Aldous Huxley refers to as the Perennial Philosophy, the message which, through form after form, comes down relatively unchanged through the ages. In these days of planned obsolescence, when the shelf-life of new books is measured in days, I find the unchanging nature of these ideas reassuring.

![Woren Dan - Be love now: [the path of the heart]](/uploads/posts/book/211065/thumbs/woren-dan-be-love-now-the-path-of-the-heart.jpg)

![Rameshwar Dass - Be love now : [the path of the heart]](/uploads/posts/book/113959/thumbs/rameshwar-dass-be-love-now-the-path-of-the.jpg)