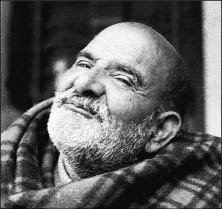

Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das.

without whom none of this would exist.

Through him I met my real self.

He wouldnt take credit for this book, but it is his.

Rameshwar Das

S PRING, 1967. I was twenty, a sophomore at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. I had just spent my first extended time out of the country on a semester abroad in Francos Spain. The Vietnam War was raging, and there was upheaval on campus.

Freshman year I took a seminar, Freedom and Liberation in Ancient China and India, that stirred an interest in Taoism and Buddhism. At the same time, I started smoking pot and experimenting with mescaline, DMT, and LSD. The visual and lyrical effects of psychedelics stimulated my artistic, philosophic, and poetic intuitions and expanded my inner and outer horizons. They didnt improve my academic standing.

That spring a flyer appeared for a guest lecture by Richard Alpert, Ph.D., formerly a psychology professor at Harvard, who had done some of his graduate work at Wesleyan. Two of his former students, Sara and David Winter, were teaching psychology at Wesleyan and had invited him to speak.

Alpert was vaguely notorious to me as an associate of Timothy Leary, a counterculture icon. They had both been fired from Harvard in connection with their psychedelic activities. Alpert had the distinction of being the only tenured professor ever publicly exorcised from Harvards Ivy League faculty. They didnt go quietly. Dr. Learys infamous 1960s commandment Tune in, turn on, and drop out had become a media mantra and a cultural strategy. Pot and acid made rapid inroads, displacing alcohol as drugs of choice. The Beatles and the Stones tripped out, and there was an atmosphere of intrepid inner exploration and raucous fun mixed with political outrage. Some of it was hedonism, some was dumb, and some of it became the bones of a generation.

Dr. Alperts talk began at 7:30 P.M . in one of the student lounges. I expected a pep talk on better living through modern chemistry (then an ad slogan for DuPont Chemical). About fifty people attended, mostly students, spread out on couches, chairs, and the carpet. Instead of a tweedy Harvard psychedelic psychologist, the speaker entered wearing a scraggly beard, sandals, and a kind of white robe or dress. Dr. Alpert had just returned from India, where his name had been changed to Ram Dass. He said it meant servant of God. He looked like a soapbox prophet in Hyde Park, which Id just seen in London.

Instead of an opening paean to psychedelics, he began to relate his experience of living for six months in an ashram in the foothills of the Himalayas. He described meeting a guru who had a cataclysmic effect on his consciousness, so much so that he sequestered himself for six months in the gurus ashram to learn yoga and meditation. This was too weird for a portion of even this avid audience, and before long some departed. After a while, someone turned out the lights, and Ram Dass continued to talk in womblike darkness. In the dark, his disembodied voice fairly crackled with a kind of energy that permeated the room. He combined the excitement of a scientist with a new discovery and an explorer in terra incognita . He continued describing his experiences and responding to questions until 3:30 A.M.

As Ram Dass spoke of the interior transformation he had undergone, I began to experience one too. Subjectively it was like a figure-ground flip when, in one of those high-contrast images, you suddenly see the space instead of the shape. In my case I went from being the center of my universe to seeing myself as just one spark of awareness among billions. I understood in that moment that we are all on an evolutionary journey toward realization through infinite time and space.

It was more than a conceptual understanding. There was a feeling of meeting together in a deep space of love, and compassion for what Ram Dass called our predicament. Two and a half years later, when I traveled to see the guru in India, I experienced precisely this feeling again, like dj vu. However it happened, an old man in a blanket, whom I also came to call Maharaj-ji, came through Ram Dass that evening. The abode of love, compassion, and oneness in which the guru lived had moved temporarily to Connecticut.

To a twenty-year-old on an intensely personal quest for identity, this was revelatory. The idea that there were other beings who had actually made and completed this journey of inner exploration that I had only imagined was astounding. Maybe the journey wasnt quite so personal after all.

The next day I sought out Ram Dass and visited with him at the Winters home. Something had clicked that needed further exploration. Whatever I had experienced, I wanted more of it. I have almost no recollection of what was said between us in that exchange. I know I felt awe and gratitude, though as we talked I realized Ram Dass was very much on his journey, as I was on mine. Later I came to realize he sometimes had a difficult time when people associated him with the transmission of that state. What could he say? Sorry, that wasnt me talking? I think it drove him to work harder on his own stuff.

He was always completely, refreshingly out front about his own desire system and need for approval, and he used his neuroses as grist for the mill. Rather than sweep things under the rug, he used the meanderings of his psyche as humorous fodder for his talks. There was no holier than thou. It was more wholly than holy, more practical than pious. I think other people, too, appreciated how Ram Dass used himself as a case study for his inner research. The confluence of his psychological training, his openness from psychedelics, and his synthesis of Eastern religion made him a perfect resource for consciousness evolving during the upheaval of the 1960s. He managed to bring it together in understandable language. And it didnt hurt that he told a good story.

Over the next two years I drove up periodically from Wesleyan to visit Ram Dass, following I-91 from Connecticut through Massachusetts to where he was staying at his familys summer place, a farm on a lake near Franklin, New Hampshire. In warm weather he stayed in a tiny guest cottage without water or plumbing that he made into a cozy retreat, or kuti, where he meditated, practiced yoga, and cooked a daily pot of khichri, rice and lentils mixed together. In the winter he moved into the servants quarters of the main house in the attic over the kitchen.

Ram Dass taught me the basics of yoga and meditation and recommended some of the writings of the saints and yogis he had come to know of in India. Pranayama (breath energy practices) and saying mantras (sacred syllables) became part of my routine. I learned to cook khichri and make chapatis, Indian flatbread.

Ram Dasss father, George Alpert, was a lawyer who had been president of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. He and his fiance, Phyllis, were often at the house when I came up to visit Ram Dass in Franklin. They were extraordinarily hospitable, and I felt like extended family. Clearly Ram Dasss new manifestation had left them at a loss after his career at Harvard, but they loved who he had become, and they didnt really care why. George continued to call him Richard and seemed bemused by the assortment of mostly young people who kept turning up. It was all a bit of a mystery, but the love had infected them too.

![Woren Dan Be love now: [the path of the heart]](/uploads/posts/book/211065/thumbs/woren-dan-be-love-now-the-path-of-the-heart.jpg)

![Rameshwar Dass - Be love now : [the path of the heart]](/uploads/posts/book/113959/thumbs/rameshwar-dass-be-love-now-the-path-of-the.jpg)