All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

Originally published by Writers and Readers, Inc.

Copyright 1993

Cataloging-in-Publication information is available from the Library of Congress.

Table of Contents

Lets answer the second question first.

First name is pronounced like the English girls name, Michelle. Foucault is foo as in fooey, plus co as in coco-nut, coming down harder on the coconut.

Who was he?

A French guy, of a peculiar French type,

THE FAMOUS

INTELLECTUAL.

The Famous Intellectual of the generation before his was

JEAN-PAUL SATRE,

who really defined the type: a thinker with thoughts on a wide variety of subjects, popularly recognized as an important national resource, expected to say brilliant, unexpected things,to get involved in politics from time to time, and to symbolize knowledge and thought for the nation and the world.

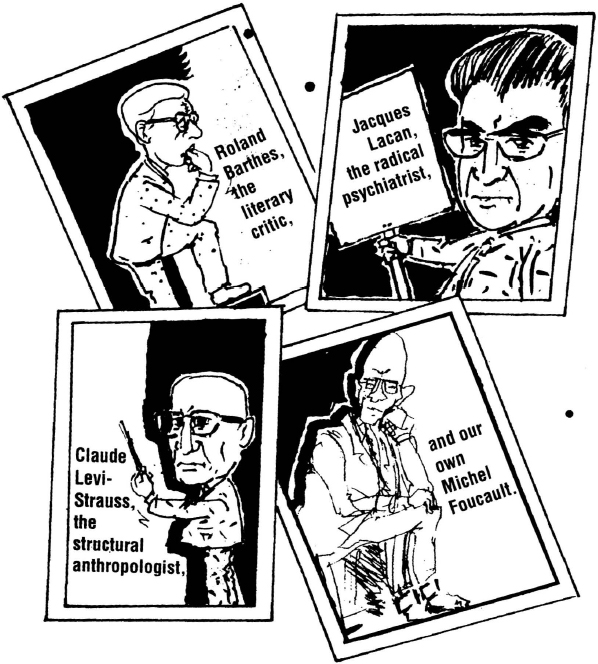

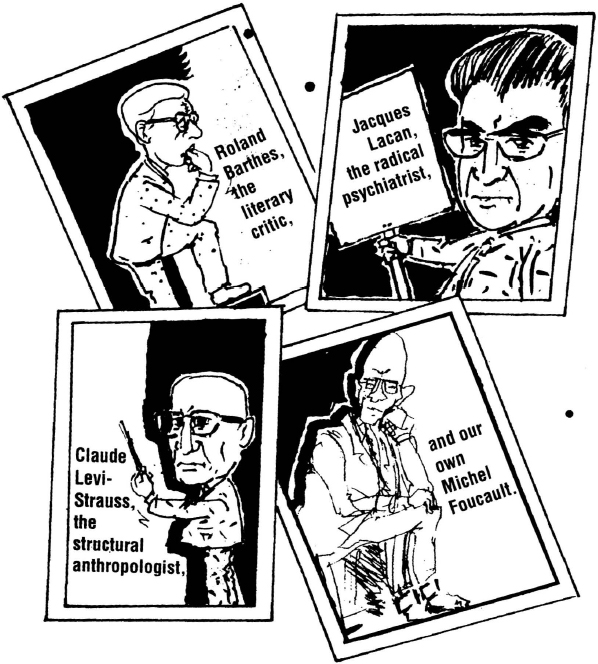

A fter Sartre, there was no agreement about who stood on the intellectual pinnacle.

Struggling towards the peak in the sixties were:

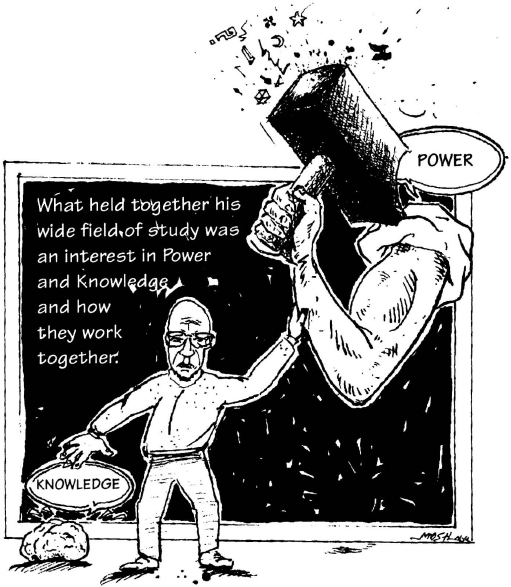

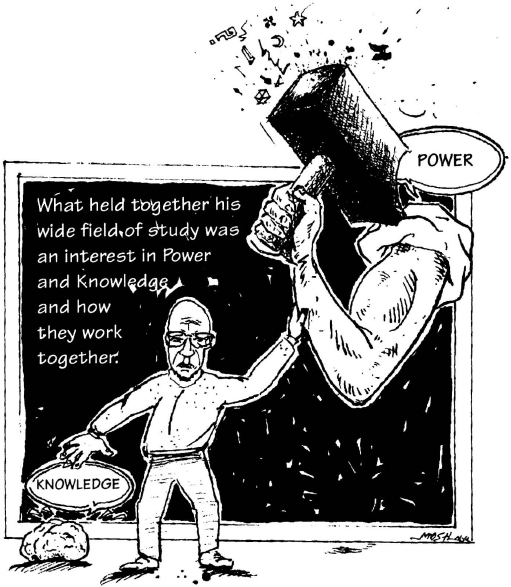

H e worked in so many different fields that it is very hard to categorize his work. In a bookstore today you might find his books in Philosophy, History, Psychology, Sociology, Medicine, Gender Studies, and Literary or Cultural Criticism.

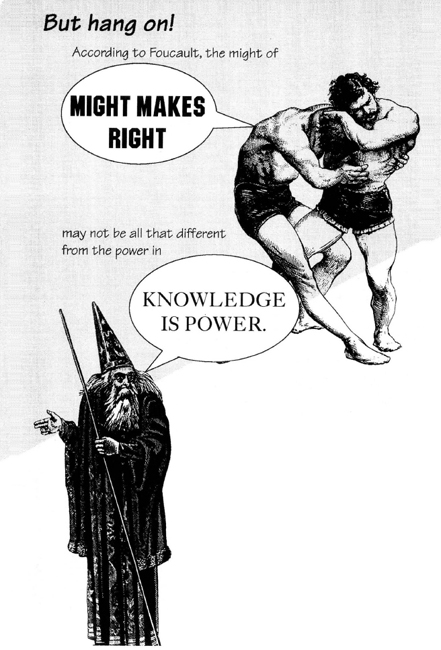

You might say he started with the truism

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER,

took it apart, analyzed it, and put it back together. He was particularly interested in Knowledge of human beings, and Power that acts on human beings.

Suppose we start with the statement

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER

but doubt that we have any knowledge of absolute truth.

If you take away the idea of absolute truth, what does knowledge mean?

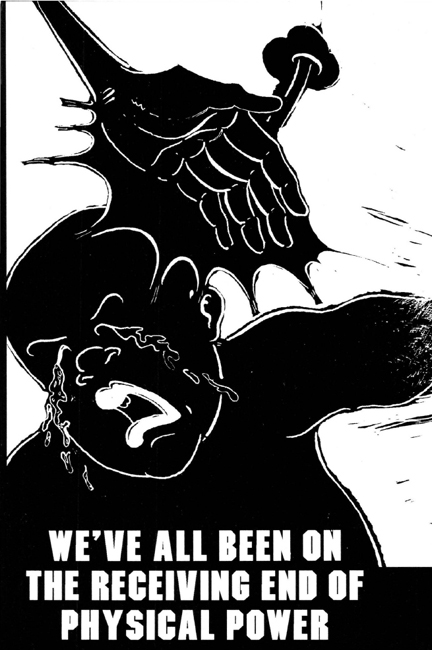

In one case physical force, in the other mental force, is exerted by a powerful minority who are thus able to impose their idea of the right, or the true, on the majority.

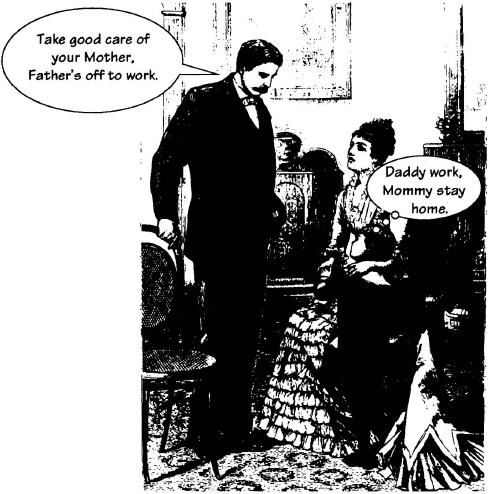

W hen were talking about knowledge of human beings, the social sciences, or, as Foucault calls them, the human sciences, then the people deciding what is true (constructing Truth) are deciding matters that define humanity, and affect people in general. If they can get enough people to believe what they have decided, then that may be more important than some unknowable truth.

But hang on!

How do some people get the rest of us to accept their ideas of who we are? That involves some power to create belief. And these same people who decide what is knowledge in the first place can easily claim to be the most knowledgeableto know more about us than we do ourselves.

B ut how does knowledge/power get its work done? Often knowledge/power and physical force are allied, as when a child is spanked to teach her a lesson. But primarily knowledge/power works through language. At a basic level, when a child learns to speak, she picks up the basic knowledge and rules of her culture at the same time.

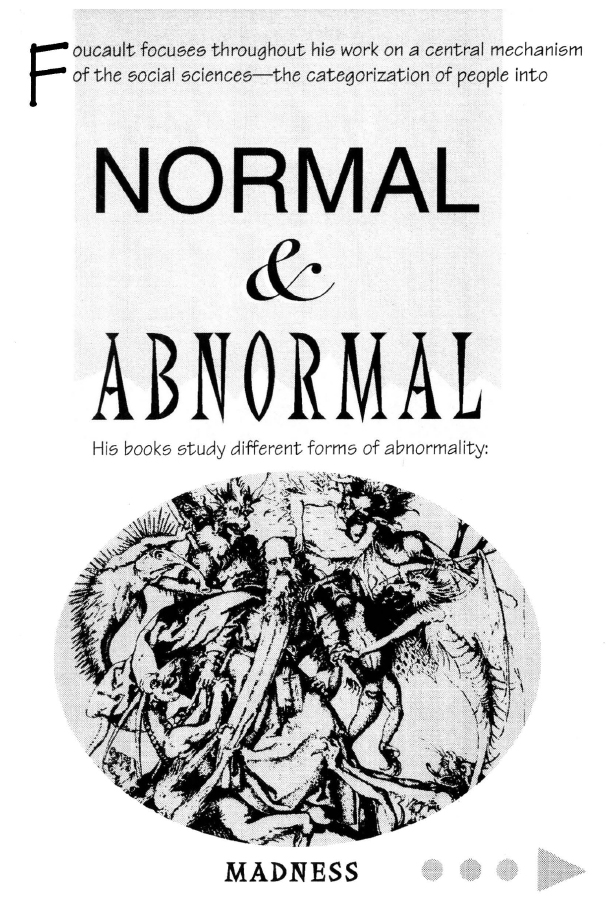

On a more specialized level, all the human sciences (psychology, sociology, economics, linguistics, even medicine) define human beings at the same time as they describe them, and work together with such institutions as mental hospitals, prisons, factories, schools, and law courts to have specific and serious effects on people.

We would naturally tend to define

as everything which differs significantly from the

But by looking at a wide variety of historical documents, Foucault challenges all of these assumptions. He shows that definitions of madness, illness, criminality, and perverted sexuality vary greatly over time.

Behavior that got people locked up or put in hospitals at one time was glorified in another.

Societies, knowledge/power, and the human sciences have, since the 18th century, carefully defined the difference between normal and abnormal, and then used these definitions all the time to regulate behavior. Distinguishing between the two may appear to be easy, but is in fact extremely difficultthere is always a hazy and highly contested borderline.