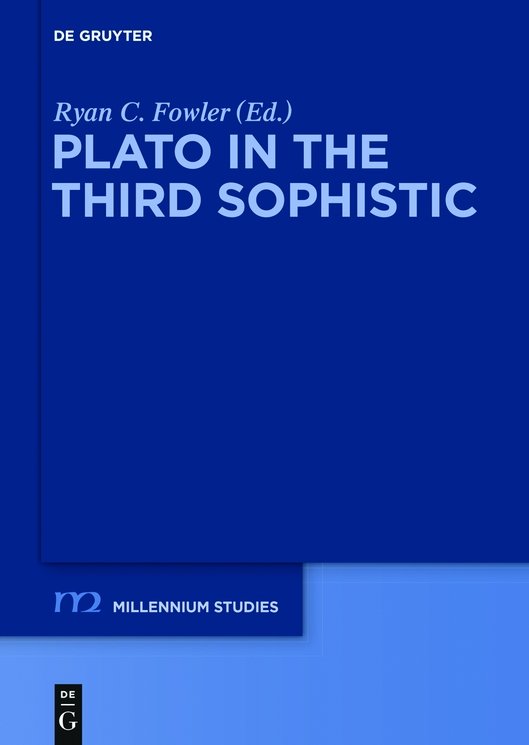

Fowler Ryan - Plato in the Third Sophistic

Here you can read online Fowler Ryan - Plato in the Third Sophistic full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Boston, year: 2014, publisher: De Gruyter, Inc., genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Plato in the Third Sophistic

- Author:

- Publisher:De Gruyter, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- City:Boston

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Plato in the Third Sophistic: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Plato in the Third Sophistic" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Plato in the Third Sophistic — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Plato in the Third Sophistic" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I would like to thank all the contributors to this volume, who worked hard to examine the use and impact of Plato in late antiquity in new and interesting ways: I appreciate all of your diligence and patience.

I would like to offer a heart-felt thank you to Professor Alain Gowing, who extended to me all the resources and support I could have possibly needed at the University of Washington as a Visiting Scholar for the 20132014 academic year. I owe a thank you as well to the Center for Hellenic Studies for a year-long Curriculum Fellowship. And I would like to offer my appreciation to Franklin & Marshall College for the office space and library access I needed in the last stretch of this project.

This volume would not have been completed if it werent for Michiel Klein Swormink and his colleagues at De Gruyter. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank the series editors of Millennium-Studien: Wolfram Brandes, Alexander Demandt, Helmut Krasser, Hartmut Leppin, Peter von Mllendorff, and Karla Pollmann.

Lending his copyediting skills, Erik Hane worked quickly and often at a moments notice; Luke Madson as well helped me avoid errors and omissions in the volume; and Sean Mills provided essential help with the Prolegomena and Introduction.

Regarding translations, Jessica Crockett translated the contribution by Bernard Schouler; Kate Brooks translated the work of Michael Schramm.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Professor Robert Penella, who translated the piece by Claudia Greco, helped smooth out some of the translations (both modern and ancient) of a number of the contributions included in this volume, as well as offered his advice on a number of logistical and structural issues. The idea for this book really began during a long lunch with Professor Penella a number of years ago in a small Italian restaurant in the Bronx. This volume would not have been possible without his constant (and tireless) guidance, support, and inputreally, it should be listed as a co-edited volume. I thank him for all of these things from the bottom of my heart.

I would like to offer big thank you to Amy Elisabeth Singer for her support and help and all sorts of small things that can sometimes be forgotten or lost along the way. Her copyediting skills have again saved me from all sorts of embarrassing errors.

Last, I take responsibility for any errors in this volume.

Lancaster, April 2014

John F. Finamore (The University of Iowa)

Although there is certainly truth to Dodds claim that Iamblichus favored an approach to philosophical enlightenment that depended heavily on ritualistic and religious beliefs, there is also much more rationalism in Iamblichus writings than Dodds gave him credit for. Further, the concept of the irrational in Platonism does not begin with Iamblichus but has a long tradition. In this paper I will explore Iamblichus use of rationalism and irrationalism in his philosophy, especially as it is expressed in his De Mysteriis, and will show how it is part of a larger Platonic tradition. I hope to show that Iamblichus is not any more irrational than many of his Platonic predecessors and in many ways is more rational.

I wish to explore two areas of what 20th-century analytic philosophers would have considered irrational: demonology and the souls of the dead. As I hope to show by the end of this paper, one persons irrational is anothers serious philosophical concern.

The use of irrationalism and even what we might call magic begins with Plato himself. To begin with demonology, Plato tells us that

interpreting and carrying matters human to the gods (prayers and sacrifices) and matters divine to humanity (commands and repayments for the sacrifices). Since it is in the middle, it completes both, so that everything is bound itself to itself. Through it, all the mantic art proceeds, the art of priests concerning sacrifices, rites, spells, and every mode of divination and magic. God does not mix with humanity, but through it is every communion and exchange between gods and human beings, for those who are awake and asleep.

It should be noted that the daemons are cosmos to the realm of the Forms beyond the sphere of the fixed stars (246e6 247a1). They, like the gods, travel easily to the world of the Forms. Thus, Plato gave daemons a special place and useful role in the cosmos.

Plato also discusses Plato is not giving the reader a classification of ghosts. Rather he is taking their existence for granted and using that common belief in ghosts to support his contention that non-philosophical souls retain some amount of corporeality. The relationship between ghosts and souls is easy enough to see. Ghosts that wander graveyards were once humans who were too attached to this realm. Plato does not assert any relationship of these ghosts to daemons, and this fact opened up an area for later Platonists to ponder.

The third head of the Plutarch reports that Xenocrates relates the gods to equilateral triangles, daemons to isosceles, and human beings to scalene, thereby showing geometrically the intermediary status of daemons. The equilateral has three equal angles and sides, the isosceles two equal angles and sides, and the scalene none. Thus the isosceles is intermediate in the sense that it is partially like the divine equilateral (having two equals) and partially like the human (having one unequal), just as daemons share immortality with the gods and

The role of the triangles is puzzling. Plato in the Timaeus had the Although we lack sufficient evidence to be sure, we can at least see that the triangles are different in type and the different characteristics mark off one kind of living thing from another.

There is one more aspect of the

Xenocrates thinks that unlucky days and any feasts that involve some blows, lamentations, fasts, abusive speech, or obscenities are unrelated to honors given to gods and good daemons but that there are in the environment around us natures that are great and strong but intransigent and sullen that delight in such things and, when they happen upon them, turn themselves to nothing worse.

Xenocrates here introduces a group of evil daemons and distinguishes them from both the gods and from a second, better group of daemons. He is, of course, taking heed of a class of daemons sanctioned in the ordinary, non-philosophical Greek world, but the inclusion of evil daemons represents a change from Platos doctrines and will become a problem that will have to be dealt with later in the Platonic tradition, as we shall see. How these daemons mesh with the triangular categories of the De Defectu is not easy to see. Perhaps they are every bit as scalene as human beings, although it seems that since the quality of being scalene relates to mortality, evil/irrational daemons would still have to be isosceles, but a different sort of isosceles than the good/rational daemons.Xenocrates included a class of evil daemons alongside the good daemons of Platos Symposium, and he thought that these daemons were the power behind the more emotional sorts of ritual practice in Greece. The last clause in the quotation from Plutarch further suggests that, if they are not softened by obtaining what they want, they are capable of harm.

Plutarch himself was also interested in daemons, and his longer discussion of the daemons in his De Iside and De Defectu raises other considerations. Like Xenocrates, he sees the daemons as intermediaries. Citing

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Plato in the Third Sophistic»

Look at similar books to Plato in the Third Sophistic. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Plato in the Third Sophistic and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.