All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

The text of I and II Samuel, appearing here in substantially different form, is taken from Give Us A King!: Samuel, Saul, and David. Copyright 1999 by Everett Fox. Published by Schocken Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York.

On the Shimshon Cycle first appeared in different form as The Samson Cycle in an Oral Setting in Alcheringa: Ethnopoetics 4:1 (1978).

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Augsburg Fortress Publishers for permission to reprint the maps on from Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, by John J. Collins, copyright 2004 by Augsburg Fortress Press. Reprinted by permission.

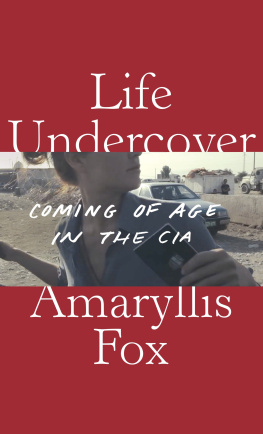

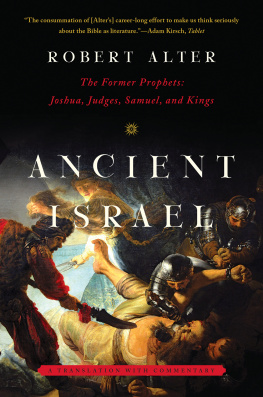

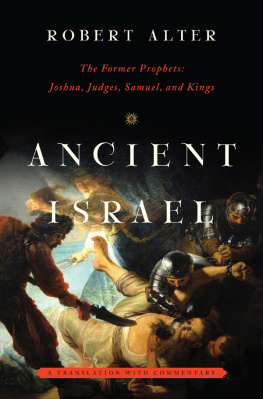

Nathan Admonishing David, by Rembrandt van Rijn, c. 1655, pen and brown ink, heightened with white gouache. Copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Source: Art Resource, N.Y.

In this memorable study, one of four he drew of the scene in II Sam. 12, the artist presents a chastened King David, scepter pointed downward, listening to the prophets rebuke. The theme of divine word versus kingly power is a major one in the books of Samuel and Kings.

C ONTENTS

T RANSLATOR S P REFACE

B Y NATURE, TRANSLATION IS A SLOW AND PAINSTAKING PROCESS MARKED BY CONSTANT rethinking and revision. Published works give an impression of finality, but in truth there is no end point for the translator, either in concept or in executiononly the ongoing attempt to draw nearer to the source. And like the experience of the performer on the stage or in the concert hall, the translators perception of the source alters with time. It is therefore only natural that I have made changes in my work over the years, from certain aspects of the overall approach to the rendering of individual words and phrases. The publication of this book gives me the opportunity to briefly explain some of them.

I remain convinced that the best way to translate biblical texts is to try to reflect their aural quality. Whatever the Bibles origins, it is clear that most writing in antiquity was read aloud, and so to experience the Bible in its spokenness is a vital way to draw nearer to it. This was one of the chief goals of the German Buber-Rosenzweig translation (19251962), which served as the initial model for my work. Attempting a translation to be read aloud means paying close attention to the shape and length of phrases, the sounds of words, and the rhythmic aspect of the text. It also involves trying to reflect conventions of biblical literature such as meanings of proper names, repetition of key (leading) theme words, allusions to other places in the text, and wordplay. Focusing on these aspects of the text constitutes a method for reading the Bible; they are fully explained in the Preface to my Five Books of Moses (1995), and are cited and explicated frequently in the Commentary and Notes to the present volume. My translation, therefore, aims to highlight features of the Hebrew text that are not always visible or audible to Western audiences.

At the same time that I have persevered in my fundamental approach, however, a number of other issues have come to the fore in my thinking. One is, simply, readability. Martin Buber (18781965) and Franz Rosenzweig (18861929), preparing for the publication of their entire Five Books of Moses several years after the appearance of the initial individual volumes, made substantial changes in their work, and Buber, resuming the project alone after World War II, incorporated further revisions. These changes toned down the at times strident innovations of the original project, derided by some early critics as Expressionist or even Wagnerian, in favor of what Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem called a more urbane languagebut without sacrificing core principles. I have sought to do the same, trying to preserve what I can in English of the Bibles unique flavor, while at the same time advocating for the poor readers case, as Buber wrote of his task in the face of Rosenzweigs sometimes difficult (Hebraized) German. The Bible is not twenty-first-century English literature, but neither is a mechanical reproduction of biblical Hebrew in English desirable or even possible. Several other recent attempts in that direction have, to my mind, foundered.

Hence I have made some changes. First, I have reduced the number of hyphenated words, which were a major feature in The Five Books of Moses. While biblical Hebrew is quite compact, often requiring two or three English words to express one Hebrew one, I do not wish hyphenation, one approach to this problem, to be such an oddity that it detracts from the texts flow, even visually. Thus I have eliminated it from constructions such as be strong, turn back, and reign as king, all of which represent a single Hebrew word. At the same time, I have chosen to retain hyphens in instances such as rant-like-a-prophet and sacrificial-altar, where I felt that it was important to keep the root meaning of the verb in view. I hope the reader will not experience this as too confusing or inconsistent.

Similarly, I have cut down on the number of words in brackets, which in The Five Books of Moses, in parenthesis form, served to indicate English words not found in the Hebrew. I have found some of these to be unnecessary and replaced others with an occasional hyphen. Again, my goal here is, within the limits of my method, to allow the text to flow unimpeded.

I have retained my previous renditions of a particular Hebrew form which uses the infinitive absolute, often to intensify the concept. Thus, in the Garden of Eden story in Gen. 2, the human is told not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, or he will die, yes, die. Most translations utilize an adverb, treating the phrase as you shall