Table of Contents

For Ellen Stewart,

the founder of La MaMa E. T. C.,

who opened her theatre to the world

Special Thanks

Suzanne Sato, Muna Tseng, Courtney Golden, Sachiko Willis, Sara Zatz, Victoria Abrash, Bruce Allardice, National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the Rockefeller Foundation, Asian Cultural Council and La MaMa E.T.C.

Preface

By Jessica Hagedorn

Around twenty-five years ago, I came across a profile of Ping Chong in one of those hip downtown paperseither the Village Voice or the now extinct Soho Weekly News. I had just moved to New York from San Francisco, and whichever alternative rag it may have been, what I know for sure is that a brief scene from the Obie Awardwinning Humboldts Current was excerpted. A photo of Pingintense, bespectacled, skinny and, at the time, long-hairedaccompanied the piece. Intrigued, I clipped the page and tacked it on the wall by the rickety, multipurpose cardtable where I ate my meals and wrote. Ping Chong would be my funky new Role Model. He was clearly some sort of maverick Renaissance mana theatre director, choreographer, filmmaker, video and installation artist all rolled into one. His being Chinese American, and creating challenging work in a world that was largely closed-off to artists of color, awakened my curiosity and was also deeply inspiring.

The first Ping Chong show I ever saw was Nuit Blanche, presented at La MaMa E.T.C. in 1981. The stark elegance and startling beauty of this production had enormous impact on me. If you ask me now what it was all about, I really couldnt tell you. But I remember, quite vividly, dialogue spoken in Spanish, a film of the moon, the sound of a bird flapping its enormous wings, and a single flower in a vase bathed in blue light. I felt as if I had watched a dream of otherness come to life onstage, and left La MaMa excited by the possibilities of making theatre.

In the years that followed, I saw as much of Pings multimedia theatre pieces as I could.

The opportunity to meet Ping in person came a couple of years later. From 19811985, I worked as the Literary and Performance Series Coordinator at Basement Workshop, a gallery space on Catherine Street in Chinatown. Founded in the early 1970s, Basement Workshop was one of the first Asian American arts organizations in the country. Its mission was to promote, preserve and present works by Asian American writers and artists. Ping seemed the perfect choice to be a part of our program. He was from the neighborhood, after allThe Local Boy Who Made Good in the Art World. We tracked Ping down and invited him to teach a performance master class. I signed up for the workshop, eager to get to know Ping and to observe his creative process.

I took a lot away from that workshop, but the most valuable thing he taught us, which stays with me even today, was how to conjure theatre from seemingly random elementsa litany of foreign and English words, a chronology of events, a song, an object from someone s home. Simply put, in that class we learned the art of juxtaposition, of which Ping is a master.

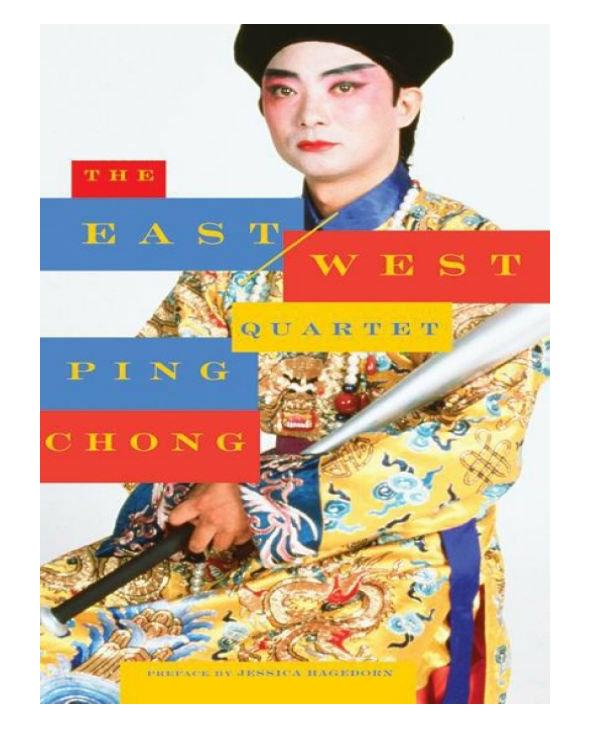

In The East-West Quartet, the reader finally gets a chance to experience and savor Pings art on the page. While Pings scripts have been anthologized widely, this is the first time a thematic body of work has been published. The East-West Quartet brings together four works which are poetic explorations of the complex and often troubled relations between East and West: Deshima (Japan), Chinoiserie (China), After Sorrow (Vietnam) and Pojagi (Korea). Ping critiques, in each dazzling and stylistically different piece, the various ways in which the U.S., the British, the French and, even the Dutch, were involved in colonizing and exploiting these four Asian countries, but the smart, tough artist in him resists the easy and the obvious. In Deshima, for example, the Americans and Europeans are not the only guilty parties. The powerful Japanese are implicated as well, for oppressing and dominating other, more vulnerable Asian countries.

Looking at history from different perspectives is a constant theme in these four works, as are identity and nation-building. Questions are raised yet, thankfully, no pat conclusions are drawn. Is history only to be written or handed down from the conquistadors point of view? How are events such as the nineteenth century Opium Wars or the twentieth century murder of Vincent Chin made different when viewed through the eyes of Asian or Asian American people? We are taken on a circuitous journey from sixteenth century Japan to the 1980s trade wars between the U.S. and Japan; from eighteenth century China to twentieth century Vietnam; and from fourteenth century Korea to present day and back again.

He has described himself as a first generation Chinese American, specifically Cantonese, who still feels a profound connection to Asia, but Ping Chong is also very much a risk-taking, singular American artist. Bold casting choices exemplify his anticipation and embrace of the multicultural explosion. In Deshima, African American actor Michael Matthews (who collaborated on the script with Ping) played the lead role of Vincent van Gogh, while a cast of Asian actors played colonizer and colonized. In Chinoiserie, an African American actress played the role of the murdered Vincent Chins grieving mother.

Austere and intimate theatre pieces, such as Pojagi and After Sorrow, or more sumptuous, epic multimedia ones, such as Deshima or Chinoiserie share certain stylistic elements that are hallmarks of Pings work: tidbits of historical information projected on a screen, the unexpected use of smart pop or classical music, the cinematic flourishes and allusions. Actors may also be called upon to waltz, make stylized gestures in the manner of Chinese opera or Restoration theatre, execute cha-cha dance steps or balletic martial arts moves.

Artfully and elegantly conceived, rich in metaphor, political yet deeply personal, the four works in The East-West Quartet tell us much about the pitfalls and ironies of history, the various contradictions, collisions and collusions within the East and the West, and the search for national and personal identity.

Ping Chong remains one of my cherished role models. A true citizen of the world, he refuses to be pigeonholed and goes his own way, as much at home on the streets of Beijing and Paris as he is on Canal Street in New York. He continues to make work that bristles with intelligence, that is filled with empathy for the human condition, that is angry yet beautifulwork that matters. It is all here in this book.

New York City

September 2004

An Interview with Ping Chong

By Victoria Abrash

VICTORIA ABRASH: Could you say a little bit about the genesis of the four plays of The East-West Quartet?

PING CHONG: Well, you want me to give you the long-winded version?

VA: The long-winded version, absolutely.

PC: When I began this project I had nothing in mind so grand as a quartet of plays about East-West relations past, present and future. But once I started down that road with Deshima and began to confront American ignorance about Asian cultures and history, thats exactly what I ended up doing.