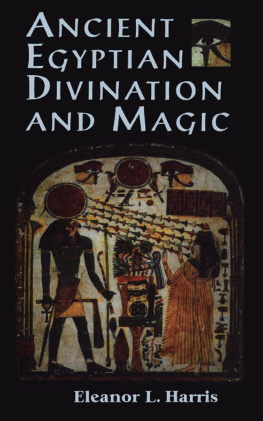

Eleanor Harris has studied and practiced Egyptian divination and magic for more than nine years. She inherited interest in Egyptian religion and magic from her father. For the past several years, Eleanor has been active in a contemporary Egyptian House of Life, which is dedicated to teaching and practicing traditional Egyptian magic. She earned her title Qematet en Tehuti, Priestess of Thoth, by authoring literary works, lecturing, and providing workshops for interested students. Her other books are The Crafting and Use of Ritual Tools, and Pet Loss: A Spiritual Guide both published by Llewellyn.

Bibliography

Allen, Thomas George. The Egyptian Book of the Dead or Going Forth By Day. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, No. 37. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Bonner, Campbell. Studies in Magical Amulets Chiefly Graeco-Egyptian, Ann Arbor, MI: Harvard Theological Review 39 (1946): 25-55, 1950.

Brier, Bob. Ancient Egyptian Magic, New York: William Morrow and Co., Inc. Quill Books, 1981.

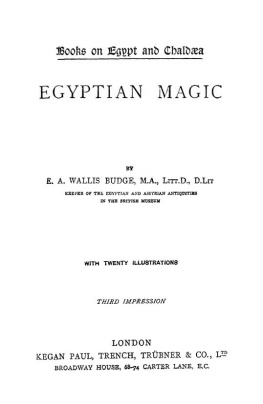

Budge, E. A. Wallis. The Egyptian Book of the Dead, New York: Dover, 1967.

. Egyptian Magic, New York: Dover, 1971.

Casson, Lionel. Treasures of the World Series: The Pharaohs, Chicago, IL: Stonehenge Press, 1981.

Clark, R. T. Rundle. Myth and Symbol in Ancient Egypt, London: Thames and Hudson, 1959, reprinted 1978.

Edwards, I. E. S. Oracular Amuletic Decrees of the Late New Kingdom, 2 vols. Hieratic Papyri in the British Museum, 4th series. London: Published by Trustees of the British Museum, 1960.

Faulkner, R. O. The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts, 3 vols. Reprint. Warminster, England: Aris and Phillips, 1978.

. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Reprint. London: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion, New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961.

Ghalioungui, Paul. Medicine and Magic in Ancient Egypt, Amsterdam: B.M. Israel, 1973.

Griffith, F. L., and Herbert Thompson, eds., The Leyden Papyrus: An Egyptian Magical Book. New York: Dover, 1974

Harris, I. R., ed. The Legacy of Ancient Egypt Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Knight, Gareth. Magic and the Western Mind. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn, 1991.

K*M*T*, A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt, 3 Volumes: vol. 6, No. 1 Spring 1995; vol. 6, No. 2 Summer 1995; and vol. 6, No. 4 Winter 1995-1996.

Jung, Carl G. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 6 Psychological Types, 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971.

de Meynard, B., and P. de Courteille, eds. Les Prairies d'Or. Paris, 1863.

Newsweek/Mondadori. Great Museums of the World: Egyptian Museum Cairo, New York: Newsweek, Inc. and Arnoldo Mondadori Editore, 1977.

Pinch, Geraldine. Magic in Ancient Egypt. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Sauneron, Serge. The Priests of Ancient Egypt. New York: Grove Press, 1960.

Time-Life Books, Editors. Timeframe 3000-1500 BC: The Age of God-Kings. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, Inc., 1987.

Watterson, Barbara. Gods of Ancient Egypt. New York: Facts on File, 1985.

CHAPTER ONE

Understanding Egyptian Religious and Magical Philosophy

Ignorance is DarknessEgyptian proverb

From the earliest times, magic was developed largely by the Egyptians in relation both to the dead and the living. Egyptian religion was grounded in a firm and active belief in the importance of magic. Ancient Egyptians believed in, and aspired to use, the power of magical amulets, spells, scripts, names, and intricate ceremonies. To best understand Egyptian magic, you need to understand their religious and magical philosophy.

Religious Philosophy

The Egyptians did not maintain a universal system of religious belief. Dogma did not exist. There were no holy texts defining strict religious doctrines requiring conformity. In polytheism, there was tolerance. The ancient Egyptians were peaceful, kind, and very aware of family values. Their religious dealings reflected this in that there were no persecutions in the name of religion.

Egyptians revered and respected all of natural existence. They did not attempt to persuade or force non-Egyptians to worship their deities, nor did they degrade the beliefs of others. In fact, the Egyptians were open-minded and receptive to other cultures' belief systems.

Ancient Egyptian religion is puzzling to a degree; it resembles Judaism, Islam, and Christianity in that it propounded a belief in a central god, the Creator, but it was also polytheistic.

Whether polytheism grew from monotheism in Egypt, or monotheism from polytheism, will remain a mystery. The evidence of the pyramid texts shows that, already in the 5th Dynasty, monotheism and polytheism flourished side by side.

While the ancient Egyptians had a pantheon of gods and goddesses, they believed in one central god who was the Creator, invisible and eternal. This one god created all in existence. This god was divine, but had lived upon the Earth and had suffered a cruel death at the hands of his enemies. He had risen from the dead and had become the God and Pharaoh of the world beyond the grave. This god was Ausar.

The following outline of beliefs taken from native religious works, some calculated to be between six and seven thousand years old, describes the basic composition of Egyptian religious philosophy:

- A central god, the Creator;

- A company of gods and goddesses possessing humanlike emotion and human-animal characteristics;

- Divine truth, order, and judgment;

- Divine battle between Order and Chaos;

- Resurrection;

- Immortality.

From primitive times and well into more civilized periods, Egyptian religious beliefs remained much the same. The Egyptians were immaculate record keepers and very conservative in maintaining early traditions. New insights gained with the passage of time were merely added to the main body of beliefs.

Order and Chaos at War

The Egyptians believed the forces of primal chaos posed a continuous threat to the world. The creation of the world had occurred in conjunction with the creation of social order and kingship, and the harmony of the universe could be preserved by practicing the principal of maat; divine truth, justice, and order. The principal of maat was the basis of the Egyptian religion, and was symbolized by the goddess Maat. She reigned over the equilibrium of the universe, the divine order of all things, and the regular cycles of the Sun, the Moon, the stars, the seasons, and time itself.

Although it was clear these chaotic forces had been tamed, only the deities could protect and defeat the eternally present threat of chaos.

The Nine Bodies: A Religious Theory

Egyptians believed that humans and other living creatures consisted of nine bodies. These nine bodies define why the Egyptians believed that it was possible to invoke a creature's life force into a statue, and thereby gain the creature's power. They believed in ghosts and apparitions, which were made possible by the existence of the ka body, and the khu body, discussed below. Through different bodies, the Egyptians communicated with the dead, projected out-of-body, assumed other creatures' power, and enjoyed other abilities that you can share today.

Next page