MESCALINE

Copyright 2019 Mike Jay

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019933930

ISBN 978-0-300-23107-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

CHAPTER FRONTISPIECES

PLATES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

At an early stage of writing Toni Melechi and Alan Piper were both very generous in pointing me towards primary sources they had uncovered in their previous researches. Thanks also to Toni for reading an early draft of the manuscript. I owe a great debt to Keeper Trout for sharing his prodigious knowledge of the botany and history of peyote and San Pedro, and for giving me detailed feedback on the manuscript. Trout works together with Martin Terry and Ted Herrero at the Cactus Conservation Institute (cactusconservation.org), an essential resource for the preservation of peyotes natural habitat; it was a great pleasure to meet Martin and Ted in Oklahoma and I thank them for their insights into peyotes current status. I owe my education in the traditional use of San Pedro (huachuma) in the Andes to Anthony Henman (Peru), and Roberto Calzadilla and Maria Yana (Bolivia). I greatly appreciated Andrew Lees expertise in bio-chemistry and the neurosciences, as well as his fine literary judgement. Jesse Jarnow responded enthusiastically to my queries about the early years of psychedelic counterculture. Erik Davis made several invaluable connections on my behalf. Thanks also to Peter Moore for many enjoyable conversations and his stimulating feedback on the manuscript. And, as always, very special thanks to Louise, the perfect companion in these researches.

In Oklahoma: my deep gratitude to William Voelker Wahathuweeka and Troy (The Last Captive) Kwihnai Mahquuitsoi Okweettuni of Sia, the Comanche Nation Ethno-Ornithological Initiative and Piah Pha Kahni (Mother Church) of the Numunuh (Comanche) Native American Church, for their wonderful food and hospitality, their great generosity in sharing with me the history of their people and their precious life items, and for hosting the meeting that I describe in the epilogue. Udah! Warmest appreciation to Charlie Haag, President of the Native American Church of Oklahoma, for sharing with me the stories of his grandfather Mack and the founding of the Native American Church, and for making tracks with James Mooney around Calumet and Concho. Many thanks to Daniel Swan, curator of the Sam Noble Museum of Natural History in Norman, OK, for sharing his deep knowledge of the NAC and its artistic traditions, and for his generous introductions. Thanks also to Amie Tah-Bone at the Kiowa Cultural Centre in Carnegie, and Diana Cox at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa.

In New Mexico: special thanks to Mark Hoffman and the Bad Shaman for their hospitality in Taos and their insights into local history and ethnobotany. Thanks also to Carol at the Mabel Dodge Luhan house for her welcome and guided tour. In Gallup, many thanks to Donovan Ferrari at Silver Dust Trading and to Rick and Kathy at Shima Traders for sharing their knowledge of the contemporary NAC scene.

Among many other people to whom Im indebted for conversations, pointers and other assistance are: Ian Baker; Michael Bird; Jacob Blandy; Paul Bloom; Joseph Calabrese; Ru Callender; Anthony Day and Ross Macfarlane at the Wellcome Library; Rob Dickins; Patrick Everett; Colin Gale and Amy Moffat at the Bethlem Art and History Collections Trust; Richard Grant; Kathelin Gray and Chili Hawes at the October Gallery; Adam Green; Ivo Gurschler; Tim Harvey, editor of the Cactus and Succulent Journal (USA); Rhodri Hayward; Matei Iagher; Gary Lachman; Brian Leese; Rachael Lonsdale; Dave Luke and Anna Hope; Stella Luna; John Marks; Jelena Martinovic; Michael Neve; Jerry Patchen; Mark Pilkington; John Robertson of the Poison Garden, Alnwick; Sonu Shamdasani; John Smythies; Michael Somple of the Munson William Proctor Art Institute; and Beata Zgodziska at the Museum of Central Pomerania.

Many thanks for all their support and encouragement to my literary agent, Caroline Montgomery, and to my editor Julian Loose, whose early suggestions steered the book towards its eventual form.

Mescaline molecule.

Huxley maintained the correct spelling should be psychodelic and persisted with it, to little avail.

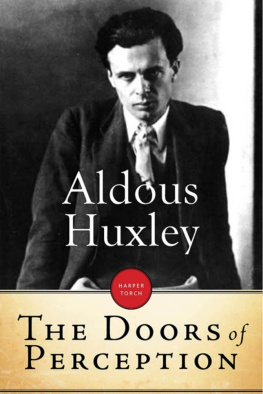

Reading it today, Huxleys book seems an improbable springboard for the psychedelic revolution. The sixties counterculture rarely recalled the high seriousness of its aesthetic canon (Bernini, Watteau, Vermeer) or its profusely capitalised metaphysical abstractions (Mind-at-Large, Istigkeit, the Dharma-Body, the Void, the Nature of Things). Most fondly remembered in the decade to come was the authors rapt scrutiny of the folds in his grey flannel trousers. At the time of its publication in 1954, however, The Doors of Perception compelled attention with two grand claims: one about mescalines future and one about its past. The first was of a scientific breakthrough, the new and perhaps highly significant fact

By the time The Doors of Perception was published, mescaline was already a hot topic in biomedical and psychiatric research. During 1953 and 1954 readers of Time and Newsweek had learned about the schizophrenia hypothesis proposed by Humphry Osmond and John Smythies on which Huxleys first claim was based. But Huxley promoted the drug to the status of popular sensation. The New Yorker gave over a dozen pages to a narrative of the healing powers and Native American ceremonies involving the peyote cactus, from which mescaline had originally been extracted. Simultaneously with Huxleys essays, articles and broadcasts about the prospect of a society in which psyche-delic drugs were used for spiritual illumination, the French artist and poet Henri Michaux was publishing the first of his gruelling investigations into the effects of mescaline on consciousness and creativity; the anthropologist James Sydney Slotkin produced his acclaimed ethnography of Native American peyote use; and the pioneers of the drug culture to come, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg among them, were adding peyote to their diets of marijuana, heroin and Benzedrine. Suddenly mescaline was everywhere.

In addition to mescaline and LSD, in 1957 a LIFE magazine cover splash announced the discovery of a new psychedelic drug. The investment banker and amateur ethnobotanist Gordon Wasson had tracked down a tribal community in Mexico which still used vision-giving mushrooms according to ancient tradition, and in 1958 Albert Hofmann, the discoverer of LSD, isolated the mushrooms active chemical and named it psilocybin. The issue of LIFE following Gordon Wassons feature Seeking the Magic Mushroom demonstrated that intrepid members of the public were already undertaking their own adventures. It included a letter from one Jane Ross advising that Wassons journey to the mountains of Oaxaca had been unnecessary: Ive been having hallucinatory visions accompanied by space suspension and time destruction in my New York City apartment for the past three William Burroughs had already sniffed out the same supplier, and within three years peyote would be on open sale in the bohemian haunts of lower Manhattan.

Next page