For Beginners LLC

155 Main Street, Suite 211

Danbury, CT 06810 USA

www.forbeginnersbooks.com

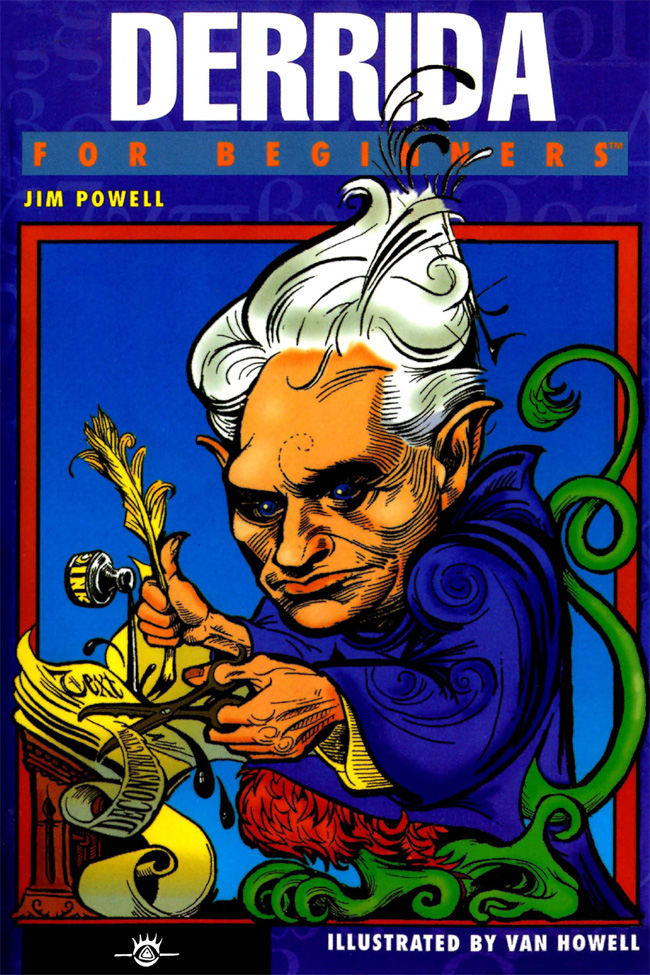

Text: 1997 Jim Powell

Illustrations: 1997 Van Howell

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

A For Beginners Documentary Comic Book

Copyright 1997

Cataloging-in-publication information is available from the Library of Congress.

eISBN: 978-1-939994-05-9

For Beginners and Beginners Documentary Comic Books are published by For Beginners LLC.

v3.1

CONTENTS

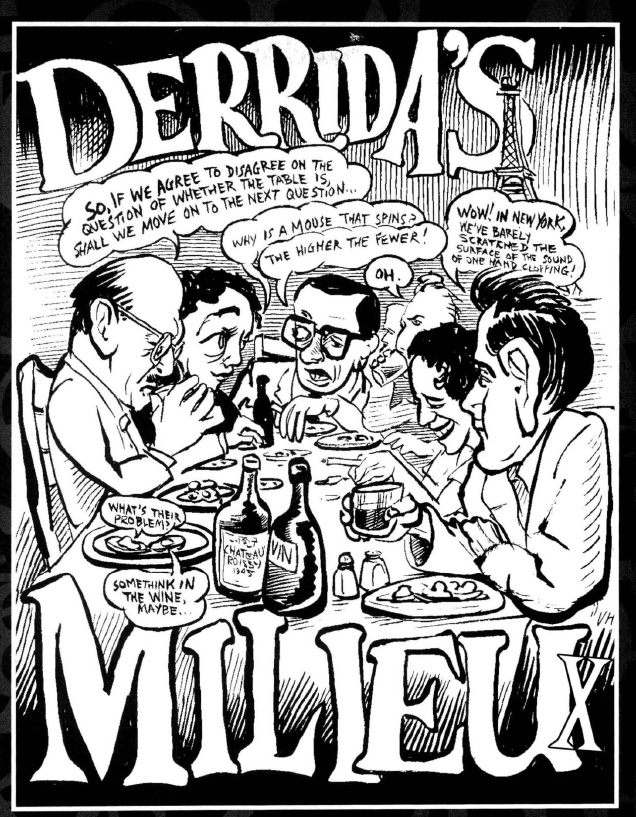

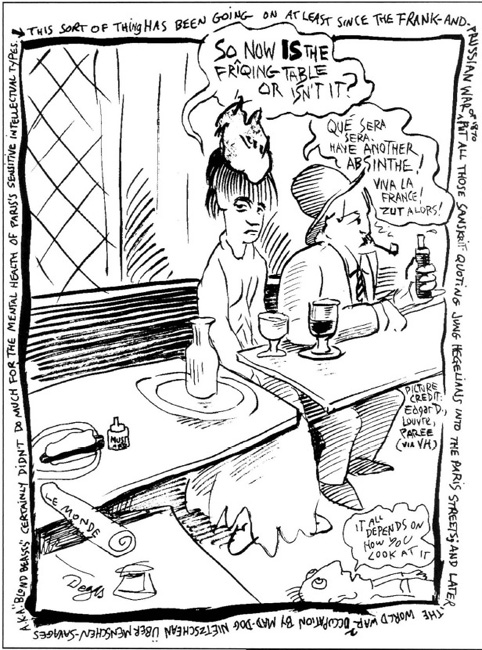

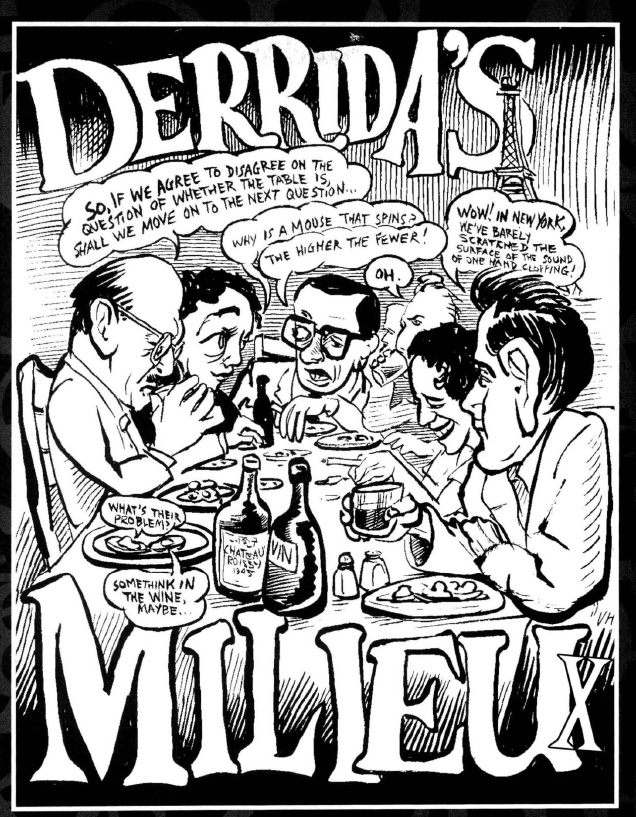

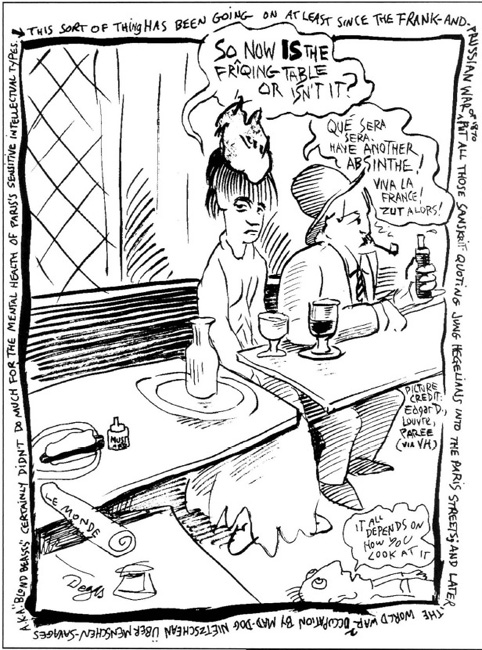

rance, for intellectuals, has long beckoned as a kind of paradise, a place where philosophers and thinkers have been looked upon as national treasures. For decades, on the sidewalks outside the cafes of Paris, light has danced down through the boughs along the boulevards, playing over the surfaces of objects, dappling tablecloths and variously attired torsos in swarms of ephemeral hues. Cafe-goers, many of them people of intelligence and culture, have placed orders, fumbled for cigarettes, and found it very attractive to be able to sit at a table and talk about the table and, raising a philosophical eyebrow in the dappled light, to ask if the table is. Such tabletalk has long overspilled the cafes and boulevards, crept in under the window sills and doorways of museums and galleries, studios and publishing houses, to permeate all the arts, including literature.

rance, for intellectuals, has long beckoned as a kind of paradise, a place where philosophers and thinkers have been looked upon as national treasures. For decades, on the sidewalks outside the cafes of Paris, light has danced down through the boughs along the boulevards, playing over the surfaces of objects, dappling tablecloths and variously attired torsos in swarms of ephemeral hues. Cafe-goers, many of them people of intelligence and culture, have placed orders, fumbled for cigarettes, and found it very attractive to be able to sit at a table and talk about the table and, raising a philosophical eyebrow in the dappled light, to ask if the table is. Such tabletalk has long overspilled the cafes and boulevards, crept in under the window sills and doorways of museums and galleries, studios and publishing houses, to permeate all the arts, including literature.

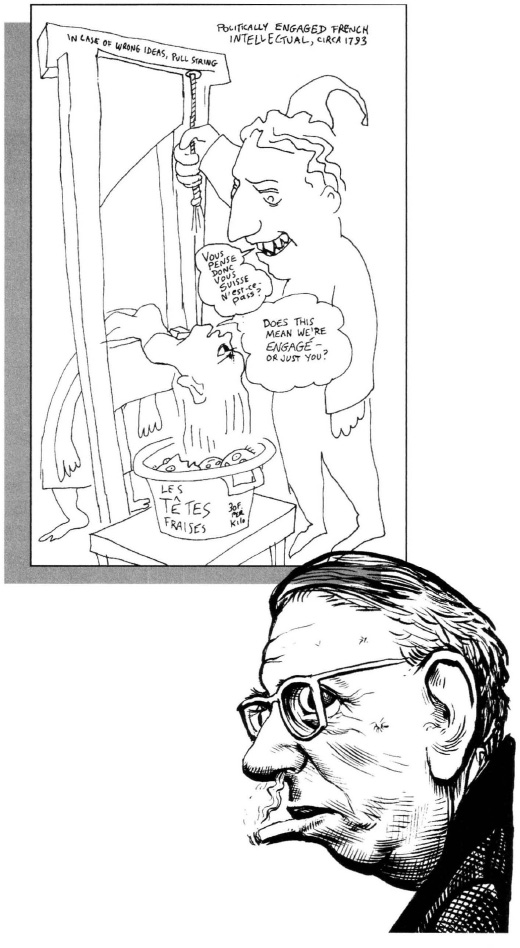

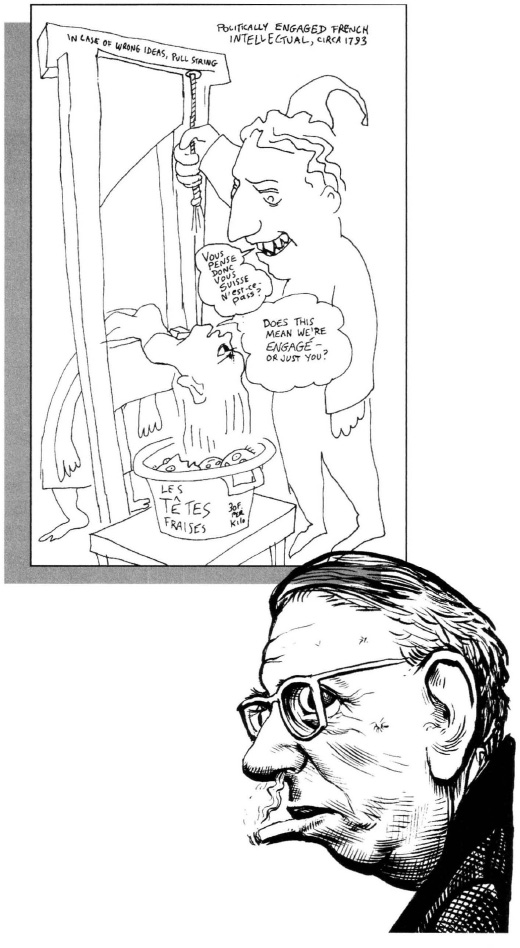

P residing over all this tabletalk, from the time of the French Revolution, the image of the philosopher was one of the intellectual engag, who, besides wondering if the table is or is not, was to be found immersed in political and public affairs, bucking the tide of established values, setting a moral tone, taking a stand, andmost importantbeing avant-garde. In recent times, up until the late 1960s, Jean Paul Sartre defined the image. Butthen the icon of the intellectual changed.

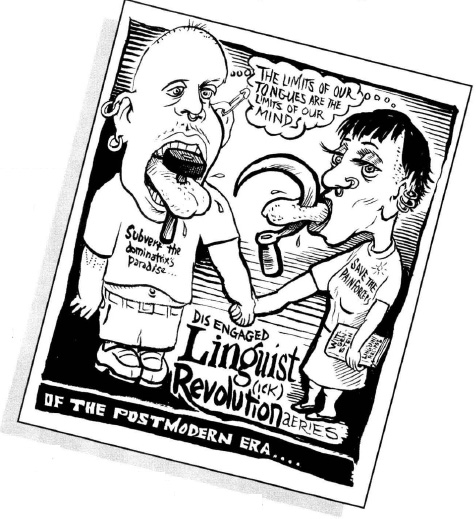

A t the same time young Americans were tripping to Jimi Hendrix, Hey Jude, Hair, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, a student movement swept across Europe. French students, supported by the Marxists, took to the streets, fighting the army and police in order to overthrow the government. They nearly succeeded, but were eventually subdued.

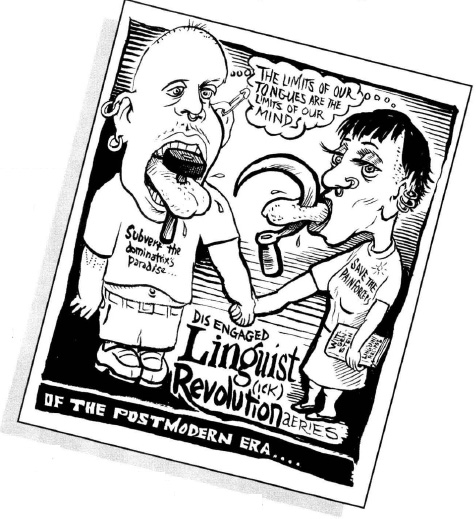

Besides, they wanted to go on summer vacation. Failing to demolish state power, they became disillusioned, inward-looking. Suddenly exhibiting a postmodern skepticism of grand myths such as Marxism and Communism, they began to commit themselves to language itself. Disengaging themselves from politics, they became linguistic revolutionaries, finding revolution in turns of speech, and began to view literature, reading and writing as subversive political acts in themselves.

I ntellectuals began attending to how words mean more than what they mean.

Increasingly distrustful of language claiming to convey only a single authoritarian messagethey began exploring how words can say many different meanings simultaneously.

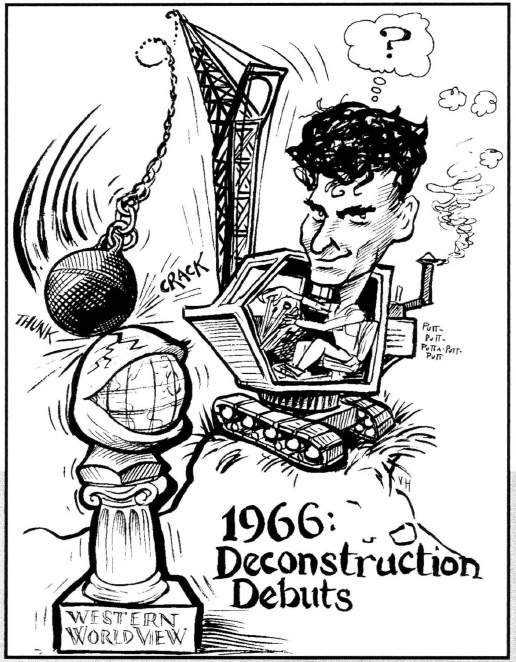

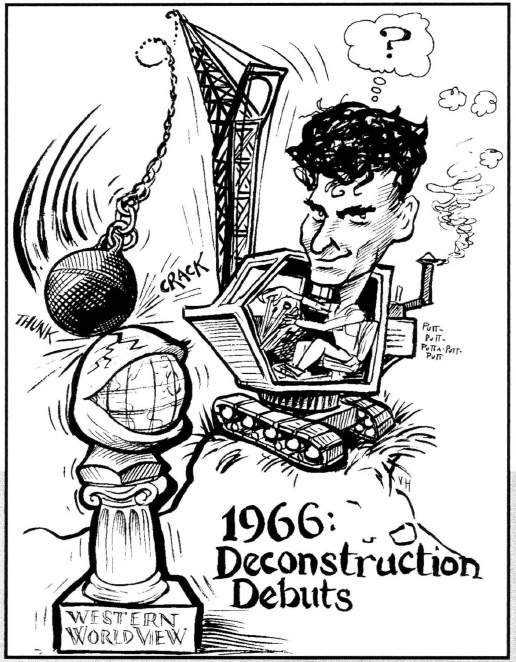

But by the time all this had taken place in France, Jacques Derrida had emerged, in the late 1960s in America, as the most avant-garde of the avant-garde. At his lecture given at the Johns Hopkins University in 1966, Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences, he had caused a stir in American academia. His thought struck a new chord that caused many previous philosophers to be reassessed, and it set the tone for much thought to come. It was something of a disharmonious chord, for his forte was a subversive mode of reading authoritarian texts, or any texts. This style of reading came to be known as deconstruction. Then in France deconstruction, kicking existentialism aside, was suddenly much in vogue. Derrida became the philosopher of the day, die new enfant terrible, the new philosopher punk, of French intellectualism. And then, after the American debut at Johns Hopkins, deconstruction and Jacques Derrida took America by storm, turning much of the Western worldview topsy-turvy.

As we shall see, Derrida was not simply a French intellectual, for the milieux influencing his emotions, intellect, and career were neither simply French nor Jewish nor Algerian nor American.

Brief

Biography

Whatever ones philosophical or critical orientation, no thinker today can ignore the work of Jacques Derrida. It was in 1966 that he was invited to present a paper at a Johns Hopkins University conference. What resulted, however, was something of a major philosophical coup. Derrida, quite unexpectedly, cast the entire history of philosophy in the West into doubt.

After this revolutionary debut, in 1967 Derrida burst upon the scene of writing with three books, Writing and Difference, Of Grammatology, and Voice and Phenomenon. Since then, the intellectual movement he spawned, known as deconstruction, has gained both admirers and detractors worldwide, bringing about a global change in the way many thinkers think. Derrida has published more than 20 books and numerous papersdividing his time between lecturing assignments in Paris and the United States. Obviously, Jacques Derrida is nobodys fool.

But for many years, he was nobodys hero either. In 1930the year the Second Surrealist Manifesto appeared; the works of Kafka, dead for several years, were emerging from obscurity; Hemingway was becoming widely read; Gides Travels in the Congo was published; D. H. Lawrence died; Singing in the Rain filled the airwaves; and the photo flashbulb popped upon the sceneJacques Derrida, son of Aim and Georgette Derrida, was born into a Jewish family in El-Biar, Algiers, his childhood dwelling a villa edenic enough to be named the garden. This domestic oasis, however, was framed by an environment where Jews were openly discriminated againstsubjected to verbal and physical violence and prohibited from entering the legal or teaching professions.

rance, for intellectuals, has long beckoned as a kind of paradise, a place where philosophers and thinkers have been looked upon as national treasures. For decades, on the sidewalks outside the cafes of Paris, light has danced down through the boughs along the boulevards, playing over the surfaces of objects, dappling tablecloths and variously attired torsos in swarms of ephemeral hues. Cafe-goers, many of them people of intelligence and culture, have placed orders, fumbled for cigarettes, and found it very attractive to be able to sit at a table and talk about the table and, raising a philosophical eyebrow in the dappled light, to ask if the table is. Such tabletalk has long overspilled the cafes and boulevards, crept in under the window sills and doorways of museums and galleries, studios and publishing houses, to permeate all the arts, including literature.

rance, for intellectuals, has long beckoned as a kind of paradise, a place where philosophers and thinkers have been looked upon as national treasures. For decades, on the sidewalks outside the cafes of Paris, light has danced down through the boughs along the boulevards, playing over the surfaces of objects, dappling tablecloths and variously attired torsos in swarms of ephemeral hues. Cafe-goers, many of them people of intelligence and culture, have placed orders, fumbled for cigarettes, and found it very attractive to be able to sit at a table and talk about the table and, raising a philosophical eyebrow in the dappled light, to ask if the table is. Such tabletalk has long overspilled the cafes and boulevards, crept in under the window sills and doorways of museums and galleries, studios and publishing houses, to permeate all the arts, including literature.