To those whose gifts remain silent

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Writing acknowledgments is a privilege, but like all worthy privileges it does not come easily. How can I fully describe the help I received? Or the trust and love that allowed this book to be? I can only hint at these things, hoping that my words will invite feelings that come nearer to the facts.

In the Fijian principle of exchange, from what is given there is a return, another giving. This book is part of that exchange; these acknowledgments, an honoring of some of the special recipients.

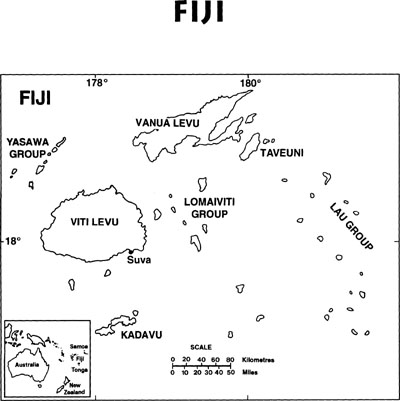

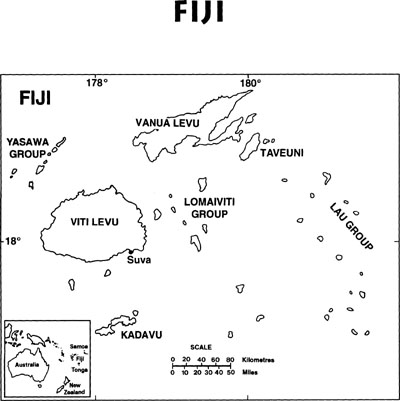

Throughout the books story I use pseudonyms out of respect and in accordance with peoples wishes. Therefore the contributions certain persons made to the book cannot be directly acknowledged. But the intensity of their contributions remains. The people I lived and worked with in Fiji the people on the island I call Kali, the island chain I call Bitu, in the city of Suva, and especially those in our adopted village, which I am calling Tovu created a home with their generosity and commitment, allowing my family and me to feel like Fijians kai viti. In the actual conduct of the research, Ratu Noa, Sitiveni, Inoke, and Tevita (the names are all pseudonyms) were the inner heart of the work. From their spirit came direction. Help also came with an open heart from Joseph Cagilevu, Ron Crocombe, Ratu Lala, John Lum On, G. Fred Lyons, Sereana Naivota, Tevita Nawadra, Asesela Ravuvu, Vula Saumaiwai, Chris Saumaiwai, Suliana Siwatibau, and Ateca Williams.

The Fijian government, especially the Ministry of Fijian Affairs, granted permission for the research and sensitively supported my efforts, as did the Fiji Museum, the Fijian Dictionary Project, and the Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific.

The writing itself drew on many sources of strength and insight, especially Ratu Noa and Sitiveni. Others who offered careful and caring readings of various drafts included Beth Cuthand, Robbie Davis-Floyd, Jackie Gusaas, Eber Hampton, Mary Hampton, Paul Jacoby, David Miller, Danny Musqua, Asesela Ravuvu, Verna St. Denis, and Bob Williamson. With dedication and insight, Merloyd Lawrence took in the manuscript and helped craft it into a book. In the process she helped clarify my larger aims in writing.

The earliest stages of writing emerged within several fertile contexts: an informal writing group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, whose members were Mel Bucholtz, Steve Gallegos, and Laura Chasin; a conference on discourse in the South Pacific organized by Geoff White and Karen Watson-Gegeo at the Claremont Colleges; an article I coauthored with Linda Kilner on the straight path; and classes taught at Harvard University, the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College, where students enriched the material I presented with their open listening and honest response.

Harvard University, the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, and the Saskatchewan Indian Federated College provided financial and logistical support in the preparation of the manuscript. The Saskatchewan Indian Federated College, where I now teach, was especially generous, offering support from the heart. With care and dedication, Louise McCallum typed the manuscript, Dave Geary made the drawings and map, Grant Kernan produced prints, Paul Thivierge reproduced slides, and Pat Jalbert expertly guided the complex production process.

I would not have gone to Fiji, and certainly not have survived there, without my family. My ex-wife, Mary Maxwell West, my daughter Laurel Katz, and my son Alex Katz were my bedrock there. Each tried to keep me straight in what I saw and said and continue to see and say.

As I write now, far from Fiji, I want to speak of my new family. My wife, Verna St. Denis, teaches me about honesty, respect, humility, and the struggle to be without the aid of entitlements. She offers these gifts to the writing of the book. Laurel and Alex bring new light to my writing task as I reflect on their beautifully emerging maturities. And now there are two new lives, our son Adam, whose smile penetrates to the heart, and our daughter Hannah, whose grace encircles us. Their energy makes my writing time more precious.

I hope this book expresses the yearnings of those who took part in its creation, and that in my struggle to follow the straight path, I will be able to return their gifts.

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1993

Royalties received by the author from the sale of this book will be shared with those in Fiji who made it possible for me to learn about the straight path.

Coming In: Exchange and Responsibility

You must tell the story of our healing. As that story educates your Y people in our ancient ways, it will help us appreciate more who we I are and who we must remain. Ratu Noa spoke calmly, looking firmly into my eyes. I listened carefully to this traditional Fijian healer I had worked with closely for nearly two years. He continued: Sometimes our story must be told by one of us from the inside; sometimes by one of you from the outside. The times determine which version of the story will be believed, and therefore which version should be put forth.

Today our story must be told by someone like you. And Im happy about that because you know our story. You look like one of them, but youre really one of us! Ratu Noa smiled. Its an exchange, he observed. Weve taught you, and now you must teach others what youve learned.

Ratu Noas words are more than a request; they are a charge; they create more than a responsibility; they create an obligation. They strengthen similar words spoken by other Fijians with whom I worked. This book is my attempt to share what I learned and am learning; to deepen my responsibility so that a true exchange becomes more possible, expanding the process of learning from Fijian healers to include a concrete giving back to those who are my teachers.

Yet I remain clear about the limits of this exchange. A voice from the outside can indeed become eloquent at a certain point in time just because it is from the outside. And spiritual families do form, bringing one within the heartbeat of another culture. I believe that happened with me in Fiji. But I can never forget that as a white person raised in the middle class, I am also forever and fundamentally different from the Fijian people I worked with. It is only by respecting the boundaries of difference, while stretching across them emotionally and spiritually, that I can hope to tell an accurate story always realizing that it is just one version or one part of the story.

How did I come to meet this Ratu Noa? The enduring gray skies and commitment to the mentality of cold which shaped my Cambridge, Massachusetts world in those days had little connection with the warm flow of air and thriving green vegetation of the tropical world of Fiji. Yet, motivated by my long-standing involvement in traditional, spiritual healing, I found myself in Fiji, with Ratu Noa.

Planning for the trip began when my then wife, Mary Maxwell (Max) West, a doctoral student in child development, was awarded a grant to do field research anywhere in the world. Together we sought a place where her research interests and mine could both be realized. We considered returning to the Kalahari Desert, where I had worked earlier with Zhu/twa (or !Kung) healers. But with two small children, we decided that the desert site was too remote from medical assistance.