Abbreviations

Quotations from Paters works, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the ten-volume Library Edition (London: Macmillan, 1910; reprint, New York: Johnson Reprint, 1973), abbreviated as follows:

| A | Appreciations |

| EG | Essays from the Guardian |

| GL | Gaston de Latour |

| GS | Greek Studies |

| IP | Imaginary Portraits |

| ME I | Marius the Epicurean, volume I |

| ME II | Marius the Epicurean, volume II |

| MS | Miscellaneous Studies |

| PP | Plato and Platonism |

| R | The Renaissance |

In addition, I have quoted extensively from Aesthetic Poetry, which was originally part of Poems by William Morris ( Westminster Review, 1868). The essay is now most conveniently seen in Harold Blooms edition of Pater, abbreviated here as follows:

| B | Selected Writings of Walter Pater, ed. Harold Bloom (1974; reprint, New York: Columbia University Press, 1982). |

Acknowledgments

Sections 4, 5, and 6 of Part Three appeared under the title Typology as Narrative Form in English Literature in Transition 27:1 (1984), 1133. I am grateful to the editor, Robert Langenfeld, for permission to reprint.

Two institutions have materially supported this work. The Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute of Radcliffe College provided a years fellowship, during which the manuscript was begun, and the community extending from that institution has been lastingly valuable to me. The Humanities Foundation of Boston University then freed me from teaching duties for a semester, when the argument was ready for a final reformulation. I particularly thank William Carroll, who directed the Humanities Foundation and its Society of Fellows toward the model of a truly interdisciplinary conversation. Other colleagues and friends at Boston University sustained the work over the years of its production: Laurence Breiner, Patricia B. Craddock, Albert Gilman, Eugene Goodheart, Misia Landau, John T. Matthews, Katherine OConnor, and David Wagenknecht. I am grateful to them for their advice, their support, their responses to chapters in progress, and their good company.

My dedication celebrates a long-standing intellectual and personal debt to Cecil Lang. Walter Paters prose is only one of the many gustatory pleasures I owe to his great generosity. His guidance repaired the work as often as his wit repaired me. Rachel Jacoffs reading of Dante is more present in these pages than their nineteenth-century focus would make evident. I thank her as well for many other gifts of a compendious intelligence, now invisibly at work in this book. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick strengthened and enabled the work throughout, in part by inspiring a vision of future work to be donefor which I am especially grateful. Nancy Waring, too, contributed important generative questions and continuing help in answering them. Other friends have steadfastly made it possible for me to imagine an audience by being one: Joyce Van Dyke, Barbara Harman, Lin Reicher, and Eleanor Ringel. Rosemarie Bodenheimer, Marjorie Garber, Barbara Johnson, and Mary Poovey have repeatedly aided my thinking and writing. I owe a special debt to the members of the ID 450 Collective, whoboth collectively and individuallyencouraged the practice of form and voice. Writing has become a different sort of pleasure with Mary B. Campbell, Susan Carlisle, Mary Wilson Carpenter, Anne Janowitz, Nancy Munger, Beth OSullivan, Helaine Ross, Eve Sedgwick, Deborah Swedberg, Martha Sweezy, Nancy Waring, and Patricia Yaeger in mind. And Bernhard Kendler of Cornell University Press contributed to the completion of this project in many invaluable ways. I thank him for the acuity of his insight, for deft intervention at crucial moments, and for suggestions of remarkable background reading.

I am grateful to my parents, Mary and James Williams, and my sister, Nancy Williams: their support has been both incalculable and essential. Finally, my deepest thanks go to my husband and colleague, Michael McKeon. I am happy that my debts to him will continue to appreciate as time passes.

Carolyn Williams

Boston, Massachusetts

1 That Which Is Without

To regard all things and principles of things as inconstant modes or fashions has more and more become the tendency of modern thought. Let us begin with that which is withoutour physical life. Fix upon it in one of its more exquisite intervals, the moment, for instance, of delicious recoil from the flood of water in summer heat. What is the whole physical life in that moment but a combination of natural elements to which science gives their names? But these elements, phosphorus and lime and delicate fibers, are present not in the human body alone: we detect them in places most remote from it. Our physical life is a perpetual motion of themthe passage of the blood, the wasting and repairing of the lenses of the eye, the modification of the tissues of the brain under every ray of light and soundprocesses which science reduces to simpler and more elementary forces. Like the elements of which we are composed, the action of these forces extends beyond us: it rusts iron and ripens com. Far out on every side of us those elements are broadcast, driven in many currents; and birth and gesture and death and the springing of violets from the grave are but a few out of ten thousand resultant combinations. That clear, perpetual outline of face and limb is but an image of ours, under which we group thema design in a web, the actual threads of which pass out beyond it. This at least of flamelike our life has, that it is but the concurrence, renewed from moment to moment, of forces parting sooner or later on their ways. (R, 23334)

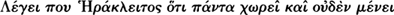

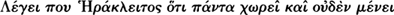

Although it serves generally to frame the essay in its place at the end of the volume, Paters epigraph, from the Cratylus, must be understood more particularly in relation to what it immediately precedes. Plato characteristically represents the words of Socrates, but in this case Socratess words themselves quote a fragment of Heraclitus: Heraclitus somewhere says that all things are moving along and that nothing stands still. Pater gives the epigraph in its original Greek, inviting translation by the initiated and implying at the same time that he himself is chief among them, for the first two paragraphs of the Conclusion in effect translate these words of Heraclitus into their nineteenth-century English equivalent. The dense and explicit intertextuality of the epigraph condenses a whole history of voices: Heraclitus and Socrates subsumed, contextualized, and voiced by Plato, whose words in turn are given by Pater as a prefiguration of his own. In this small prefatory gesture, opening with an ancient fragment in order to interpret modern thought, Pater almost ostentatiously displays his command of the entire history of Western philosophy, positioning himself at one and the same time at the latest and at the earliest verge of his traditions written record.

But even more important than Paters tacit claim to mastery of the tradition is the hint that modern thought is not so thoroughly new, but is in many ways only a modernization of the classical tradition. The epigraph quietly shows, to those who read Greek, that Pater believes the threat of modern thought to be an ancient, a persistent, even a traditional threat. For the present study, this epigraph will serve as a brief introduction to Paters habit of finding mythic recapitulations in the history of thought, since here the latest findings of science and philosophy suggest to him an analogue in Heraclitus. The epigraph enacts, moreover, one characteristic Paterian strategy of quotation, although the first two paragraphs of the Conclusion make use (as we will see) of another, more subtle and pervasive intertextual strategy.