Kannan M. (b. 1968) heads the Programme on Contemporary Tamil Culture, Department of Indology, French Institute of Pondicherry.

Rebecca Whittington (b. 1987) is a PhD student in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research interests include Tamil and Bengali modern literature, comparative literature, literary modernism, and translation studies.

D. Senthil Babu (b. 1972) is a historian of science affiliated to the Department of Indology, French Institute of Pondicherry.

David C. Buck (b. 1948) has been translating Tamil works into English since 1965. He has also studied Cittar and Saiva religion and philosophy, as well as Carnatic music on the veena. His publications include a number of collaborations with the late Dr K. Paramasivam, including a translation of Iraiyanar Akapporul with Nakkirars commentary, as well as some Sangam poetry. He has also published a translation, with comments, of Thirukkurraalak Kuravanci. More recently, he has published a number of translations from contemporary Tamil literature in collaboration with Kannan

M. of the French Institute in Pondicherry. David C. Buck is an Associate Professor Emeritus at Elizabethtown Community and Technical College in Kentucky, USA.

Introduction

Walking on my bare knees

Through a field of broken glass /

Walking on my naked soul

Through a field of broken comrades /

...

Of death / killed /

By bullets or cyanide / by

Their own or anothers hand / dead

All the same / rotting

...

Juan Gelman

A Landscape and Its People

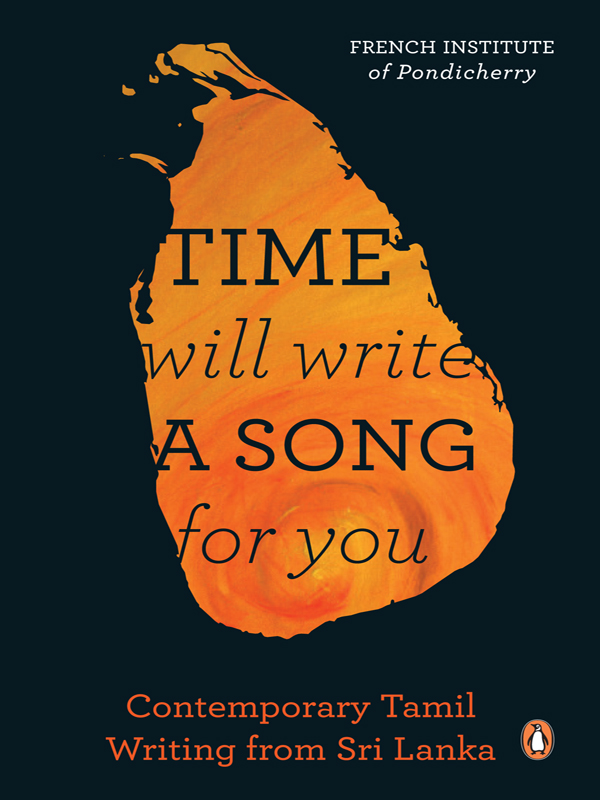

The words Tamil Writing from Sri Lankapart of the subtitle of this anthologymay invite critical discussion. Some people may say why Sri Lanka, why not Tamil Ealam? To understand this response, we have to engage with the concerns of the diverse Tamils in Sri Lanka, their roots and journey, especially over the past century and a half.

A teardrop in the Indian Ocean, the islands geopolitical location (its proximity to India and particularly Tamil Nadu) has made it a playground for the superpowers operating in the regionIndia, China and the US. Tamils in Sri Lanka, constituting 18 per cent of the population, form the main minority, and live primarily in the northern and eastern regions and in the hills of the central region. Most hill-country Tamils are descended from indentured labourers brought from South India to work on British-owned tea plantations in central Sri Lanka during the era of British rule. There is a sharp distinction made between the Sri Lankan Tamils descended from a community of people who have lived on the island for centuries, and the hill-country labourers. The ancient name for the parts of Sri Lanka populated mainly by Tamil-speaking people is Ealam. The majority Sinhalese-speaking population (74 per cent) lives in the lower central, western and southern parts of the island. Though these communities historically have been living in distinct regions within the island, they share a subcontinental religious culture, rooted in both classical and folk traditions. Further, the Tamil population itself is anything but monochromatic: besides the Sri Lankan versus hill-country division noted above, there are religion-based divisions as well. While most are Hindu, there are also many Christian Tamils and many Tamil-speaking Muslims, who live in geographically and culturally distinct regions. The major areas populated mainly by the Tamils include the Jaffna peninsula, which is the northernmost region of the island, and just to its south the Vanni, comprising the districts of Killinocchi, Mannar, Vavuniya and Mullaittivu, and the eastern coastal region centred on Triconamalai, Batticaloa and Ambarai. These communities all speak different, but mutually intelligible, dialects of Tamil, and all share in the same Tamil literary tradition.

As in India, the Tamils here are mired in hierarchies of caste and region as seen in Mahakavis iconic poem, The Temple Car and the Moon. The caste system of the Tamils here is however distinct from that of the Tamil region in India in that there has been no Brahmin hegemony. There has, however, existed a Saiva Vellala hegemony that aped the Brahmins, and has constituted its own hierarchy of lesser castes and untouchables. Regionalism among the Tamils of Sri Lanka has been sustained by the animated dominance of Jaffna, often considered the cultural capital of the Tamils, and the corresponding resentment and opposition towards it from other regions. Every other regional and caste group among the Tamils in Sri Lanka has notoriously looked down on the hill-country Tamils and considered them as yet another population of untouchables. There are other minorities, including certain tribal communities, which live in different regions of Sri Lanka.

People and their Struggle

The root cause of the struggle between the minority and the majority in Sri Lanka is the majoritarian attitude of many Sinhalese Buddhists, who are practitioners of Theravada Buddhism. An Act passed in 1956 made Sinhalese the single official language of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), thereby practically forcing the minorities into a second-order citizenship soon after independence in 1948. The two decades that followed the passing of this Act witnessed significant political turbulence that in more ways than one, sowed the seeds of the conflict to come later. Within the Tamil community, these years were characterized by the emergence of strong working-class movements led by the Communist party. The Communists, with their belief in organizing an all-Sri Lankan working class, found it important to address issues of caste oppression within the Tamil community. They led several agitations and propaganda campaigns against caste oppressionin particular, against untouchability and the denial of basic rights like access to education, water and places of worship, to the oppressed sections. The Tamil nationalist parties, with their belief in parliamentary democracy, chose to frame their politics within a language of political rights, regional autonomy and democratic federalism vis--vis the Sri Lankan state. In 1964, a pact signed by Sirimavo Bandaranaike, then Sri Lankan prime minister, her Indian counterpart, forced lakhs of disenfranchised Tamil indentured labourers living in the central hills to return to India, where they continue to live like refugees, isolated in a few hill stations, still finding it difficult to cope with the vagaries of resettlement. Those who managed to stay back faced severe hardship on the plantations, as they were harassed by their Sinhalese neighbours. As for those who resettled in other Tamil regions of the island, they faced even worse harassment at the hands of the dominant Tamil castes. Despite the serious injustice committed to lakhs of Tamil labourers, both the Tamil nationalists and the Communists staged merely token protests and continued with their set agenda. The political and social schisms within the Tamil community in the decades after 1956 prevented them from forging a unified political movement in the face of increasingly oppressive, majoritarian policies of the state of Ceylon.