ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study required so much time because access to source material was difficult. Fortunately, a large number of individuals provided me with documents that were either missing from French libraries or unobtainable, even when the collection claimed to own several different copies, the absence of which the librarians could never explain. The watchword seems to be: We keep them under tight wraps, we do not lend them out! My heartfelt thanks to Sandra Hanse (Bonn), Florence Bayard (Caen), Ronald Grambo (Kongsvinger), and Emmanuela Timotin (Bucharest), who provided me with valuable information about Romanian traditions, not to mention Philippe Gontier (Graulhet), who generously offered me the benefit of his knowledge and library, and Diane Tridoux, who sent me Dom Belins treatise from Switzerland.

INTRODUCTION

TO GUARD AGAINST ADVERSITY, MISFORTUNE, ILLNESS, AND DEATH

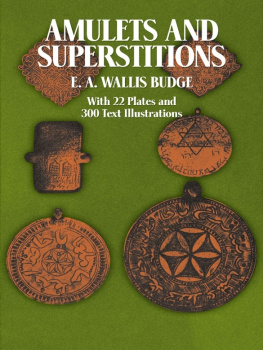

Few words are as steeped in mystery as amulet and talisman, for both are powerfully associated with the supernatural, and with the worlds of legend and fable. From the beginning, the word amulet has brought to mind protection against all kinds of assaults, while talisman plunges us deep into the arcana of the East. It inspires visions of marvelous rings and swords: in our imaginations we see those predestined heroes who have successfully fulfilled their quests thanks to an object they were given, found, or won. Such visions lead us into a world like that of The Thousand and One Nights!

But if we look around ourselves, and especially if we travel, we shall see the use of amulets and talismans in myriad placesand it is not solely the province of primitive and animist peoples. These objects are present in all of mankinds religions, sometimes in the form of a gris-gris or a holy medal, sometimes in the form of a hand or tooth. And despite whatever we may wish to tell ourselves to the contrary, belief in their virtues is very much alive in the twenty-first century. In Europe, people frequently place Saint Christopher medals in their cars; in the Far East, taxi drivers hang talismans from their rearview mirrors. People can buy talismans in Japanese temples, where such objects often take the place of an entrance ticket. The Orientalist Henri Mass notes:

As in Europe, the automobile has given amulets new popularity. Four years ago I saw shells (qoss- gorb) and lead figurines in several Tehran buses; a dried sheeps eye (nazar-qorbni), a ball of clay, or a piece of blue glass (kodji-bi) could often be seen on the radiator caps of private cars; some bus drivers wore a case on their right arms that contained a grimoire or a verse from the Koran.

Good luck charms still abound. These range from the horseshoe to the rabbits foot, from the May Day lily of the valley to the four-leaf clover. On New Years Day in Japan, people buy a hamaya in the temples, which is an arrow with the power to drive away evil spirits. The seven lucky gods (Shichifukujin) portrayed in a boat are an effective luck charm; we should also note the Inu-hariko, a paper-mach dog who not only brings luck but helps women in labor, and the Akabeko, a cow or bull made from the same material that has the power to avert misfortune. Many other such charms existed in earlier times, such as the hangmans rope or a swallows heart in Europe; the heart of a hero or a brave man in Manchuria; and peasants of the Limoges region put salt on the heads of the cattle they brought to the fair to prevent anybody from finding a way to cast an evil spell on them. In 1897, the Abb Nogus noted:

People wear over their chests or their bellies, or beneath their armpits, or hang from their necks an entire regiment of kabbalistic words: abracadabra, agla, garnaze, Eglatus, Egla, etc., as well as magical, astronomical, galvanic, magneticin other words, omnigenericamulets and talismans, which, with all due respect to the partisans of the inevitability of progress, are still highly popular!

In short, amulets and talismans are widespread among all the worlds peoples and can be found in a thousand different forms.

In France and other countries, one branch of the press is filled with advertisements for good luck medals, beneficial crosses, and so forth. In August 2000, a particular magazine offering a significant coverage of talismans could be readily purchased at any French newspaper kiosk. Among other things, this magazine provided information on how to manufacture and wear them, and what their effects would be. The magazine provided the following definition:

The talisman is both a receiver and emitter of beneficial waves and fluids, and an insulator against evil waves. It can only work for a good purpose, and only serves good actions and never helps evil deeds. Its action is the result of a combination of letters, drawings, and beneficial phrases specific to a particular domain. It is the graphic figure symbolizing your wish or desire.

Next, the magazine points out that it is necessary to wear the talisman (which seems to be stating the obvious), and that it is strictly personal and can never be given away or loaned (a claim which, as we shall see, casually contradicts all the ancient beliefs). In short, one should follow the manufacturing instructions indicated by using the illustrated figures.

On a piece of white paper, or preferably parchment (?), draw a circle a dozen centimeters in diameter in black China ink. This circle marks out the sacred space of your wish. Copy, following the example below, the magic phrase inside it and draw the seal of Solomon [two inverted triangles]. Inside the star, draw the design corresponding to your wish.

These instructions, which are devoid of scientific or magical value, are a patchwork of various esoteric doctrines, but they are interesting because they give us a glimpse of what has become of ancient beliefs that continuously adapted in accordance with the evolution of both the popular mind as well as science. There are also lavishly titled books on the market that are extremely revealing about the way in which the gullibility of our contemporarieswho, in this regard, differ little from their predecessorscan be exploited.

In order to retrace the history of amulets and talismans in the Middle Ages, it is necessary to go back much earlier and consider the earliest evidence. Prehistoric men wore amulets around their necks, such as the one found on a corpse (who was given the name tzi) in the Alps near the Austro-Italian border: he was wearing a leather pouch around his neck containing various objects. In Neolithic sites from the Bronze Age and Iron Age, fossilized sea urchins have been discovered with holes bored through them for hanging, which is evidence of their use as amulets; as recently as a few decades ago, peasants in the Clermont-Ferrand region could still be seen wearing them as good luck charms. An Arab legend states that, as a form of protection, Eve kept on her person the names that could be used to compel the obedience of demons. Older accounts have come down to us from the East and Middle East. The Persians, Chaldeans, Egyptians, Greeks, and Jews were all eager consumers for such objects.

Oddly enough, despite the increasing number of scholarly studies about daily life and different mentalities throughout history, here in France the subject of amulets and talismans has been largely left to esotericists and occultists, as well as to charlatans who cultivate no greater understanding but instead provide a captive readership with spiritual pabulum in the form of self-assured claims. This is true not only for the Middle Ages but for subsequent centuries as well. In his excellent overview of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century folk culture, Robert Mandrou, for example, devotes one chapter to the occult sciences and sorcery, but only a single paragraph to the grimoires, which specifically passed down valuable information to us,

Next page