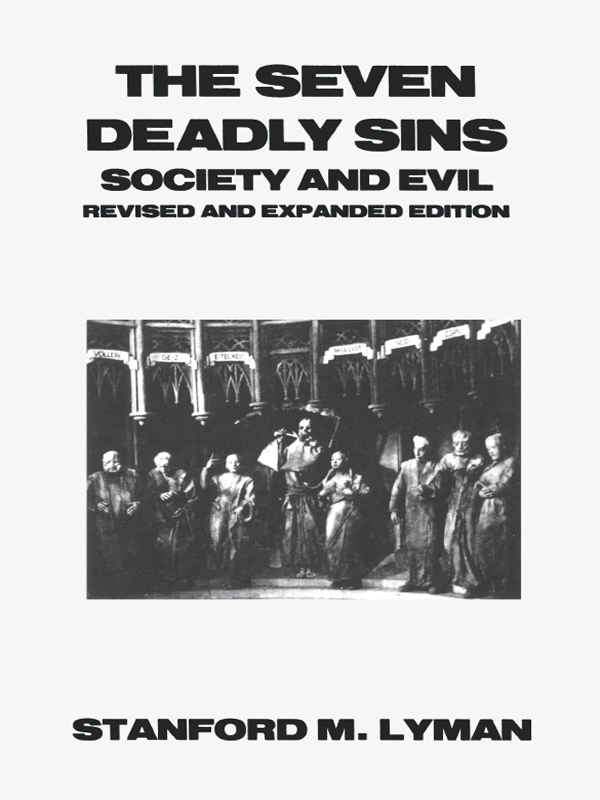

Society and Evil

Because of evil, history is a drama of conflict, not of gradual improvement.

C. T. McIntire*

It is in the modern era that man seems to be overwhelmed by evil and yet obscured from sin. What is missing in the relation of evil to sin in the contemporary era is a tissue of guilt and responsibility that connects individuals and groups to institutions and corporate structures. At the level of the individual there is the predicament of the selfsocial but amorphous, surrounded but in a lonely crowd, singular but not secure. The self, writes William Irwin Thompson, is not defined in terms of eternity, God, or even, absolutely, in terms of itself. Rather, Thompson goes on, the self is defined by others. Each man looks over his shoulder at other men to find out what he is himself. But this drama of interpersonal mirror imagery renders man all but immune from responsibility. Not responsible to himself, he is also irresponsible toward others, engaged in a never-ending display of antagonism, cooperation, and antagonistic cooperation. He is not responsible to himself; therefore he cannot know guilt, expiation, or tragic illumination. The alienation of man from himself has resulted in his loss of a defensible sense of moral worth. In its place there gnaws the existential void, the nothingness that faces evil with neither comprehension nor feeling. We seek to find the guilt in the other, to excuse or justify our own behavior. And most often we are inert. Our moral accounting creates a new theater of absurdity. As Thompson observes, There is no meaning in all this, of course: we observe a line of men, each pointing the guilty finger at the man next to him. Here there is a disappearance of meaning in which no central term can be found by which the self can be finally known.

However, a self-pitying sense of alienation of the self does not reach to the core of the matter. Instead, as the late Ernest Becker once observed, Man must confront the underlying alienation that exists in every age, and alienation exists whenever the individual does not have a commanding view, a unitary critical perspective by which to take in hand and react to the determinants of his social existence. With Becker we confront the series of obstacles that holds us back from our discovery of evil, sin, and guilt. These include the inevitable inequities in power that prevail among men, the multiplicity of visions that compete for the position of commanding views, the plurality of voices giving explanations for the evils that do exist and remedies for their elimination. The drama of power over the human condition reveals in turn the power of dramas to intimidate, coerce, or confuse mens minds.

Ultimately our own drama of evil reality concludes on a pithy note that returns us to the beginning of the story of sin. The drama is in part a masquerade. Evil is hiding, and sin lurks behind a benign persona. True hell is not in the afterlife; rather, it is here in the darkness of our own uncritical ignorance. True hell, as Nicola Chiaromonte once remarked, is in the unnecessary, in all that hides us from ourselves, hiding from us the fact that we are living in a morally dead world. In this masquerade we enjoy or lust after luxury, money, sensuality, and ease, and hope to carry these off while maintaining permanent spiritual blindness. As Chiaromonte continues, this possessiveness and greed are walled within the most deadly of the passions: inert self-satisfaction. However, inert self-satisfaction can prevail as a habit of mind and conduct only so long as the world retains its capacity to reward our efforts or, at least, not undo them. The masquerade is between man and societyeach plays the game of as if as long as it can. But things fall apart. The mutual suspension of disbelief cannot hold. Sooner or later, one confronts the othernaked and revealed. At the point of a crisis in the life-world the masks are lifted from mens eyes andif only for a momentthe fragile structure of reality is revealed. And evil is then made visible.

Our analysis of evilespecially of the sin of greed, but implicit in our other discussions as wellhas emphasized the powerful effects of crushing individuation and the transformations of corporate structures into soulless evildoers. As mans control over his own existence has diminished, some men have engineered the exploitation of things for evil purposes. Such exploitations date from the first sin. Satans single actionthe exploitation of the serpentis a model for what man does every day of his sinful life. The corporate structure of shoddy production and unequal distribution, the coercive domination of man by the authoritarian state, the employment of armaments as an extension of the violence in the human soul are each examples. Man, or rather some men, make things and other men and women the vehicles of evil and thereby hope to remove themselves from sin. If the evil is discovered the things or other people are blamed, and the evildoer excuses himself and escapes guilt, penance, and expiation. God punished the serpent for beguiling Eve, but the devil went unscathed. Human devils are often as fortunate in their own exploits. Man emulates God in punishing the agency of evil, and at the same time he exculpates himself from responsibility for the acts of his zombielike creations.

Theologically sin refers to humanitys separation from the powers and protections of the gods. Sin from this point of view is the human condition, the condition of alienation from God. In his separation from the divine he feels uncertain of his being and unknowing of his future. The material and fleshly world obsesses him, but he gains no peace of mind thereby. It is life itself that becomes a problem, and not merely particular acts in that life. Sin thus creates a drama of lifelong anxiety, as lonely, oppressed, and weighted-down individuals act or are acted upon in a theater of increasing absurdity.

As the anxieties of life itself become too much to bear, individuals seek an escape from evil, a release from sin, virtually a departure from the human condition. In their heroic struggle to release themselves from the captivity of sinful life they exchange one form of life for another, each new form promising both liberation and security, the end of mans separation from himself, from God, from history. Harold Rosenberg is thus quite correct when he interprets Marxs theory of history as a great theatrical drama. It is a play that unfolds in five mammoth, era-long actsAsiatic, Ancient, Feudal, Bourgeois, and Socialist Production. In terms of Simmels theory of the dialectics of form and life , each epoch is an act in the drama of mankinds release from the formal conditions of human enslavement and its ultimate emergence into an existence that is life itself, freed from all forms. But the forms are mans own contribution to lifehe gives it structure, meaning, rules, and customs. Encased in his own creations, architectonic man cannot escape. He can only hope for release.

Ernest Becker saw a possibility for escape from evil: Guilt must somehow be sublimated. The task of social theory is not to explain guilt away or absorb it unthinkingly in still another destructive ideology, but to neutralize it and give it expression in truly creating and life-enhancing ideologies. Becker believed that a new science of societysynthesizing ideas of Marx with those of Freudmight in its critical and tragic dimensions provide a moral equivalent of religion for the expiation of sin. A science of society, he wrote, will be a study similar to one envisaged by Old Testament prophets, Augustine, Kierkegaard, Max Scheler, William Hocking: it will be a critique of idolatry, of the costs of a too narrow focus for the dramatization of mans need for power and expiation.