TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

6163 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA

penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Bantam Press

an imprint of Transworld Publishers

Copyright Monty Lyman 2019

Monty Lyman has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Text illustrations by Global Blended Learning

The Last Judgement by Michelangelo reproduced courtesy of Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy stock photo.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781473555358

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This book is dedicated to the millions across the world who suffer in, or for, their skin.

List of Illustrations

Authors Note: Discretion and Definitions

The Hippocratic Oath states, What I may see or hear in the course of treatment or even outside of treatment in regard to the life of patients, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself. All doctors owe a duty of confidentiality to their patients, so every character with a skin condition in this book has been given a pseudonym. In some cases, particularly for those with very rare and identifiable skin diseases, I have applied a double lock of anonymity, their name being changed and the location of the meeting moved, although always to a place I have either visited or worked in.

Although it is inappropriate to define someone by a disease, such as leper or albino, I will occasionally use these terms to invite the reader into the daily reality of those suffering because of their skin.

Prologue

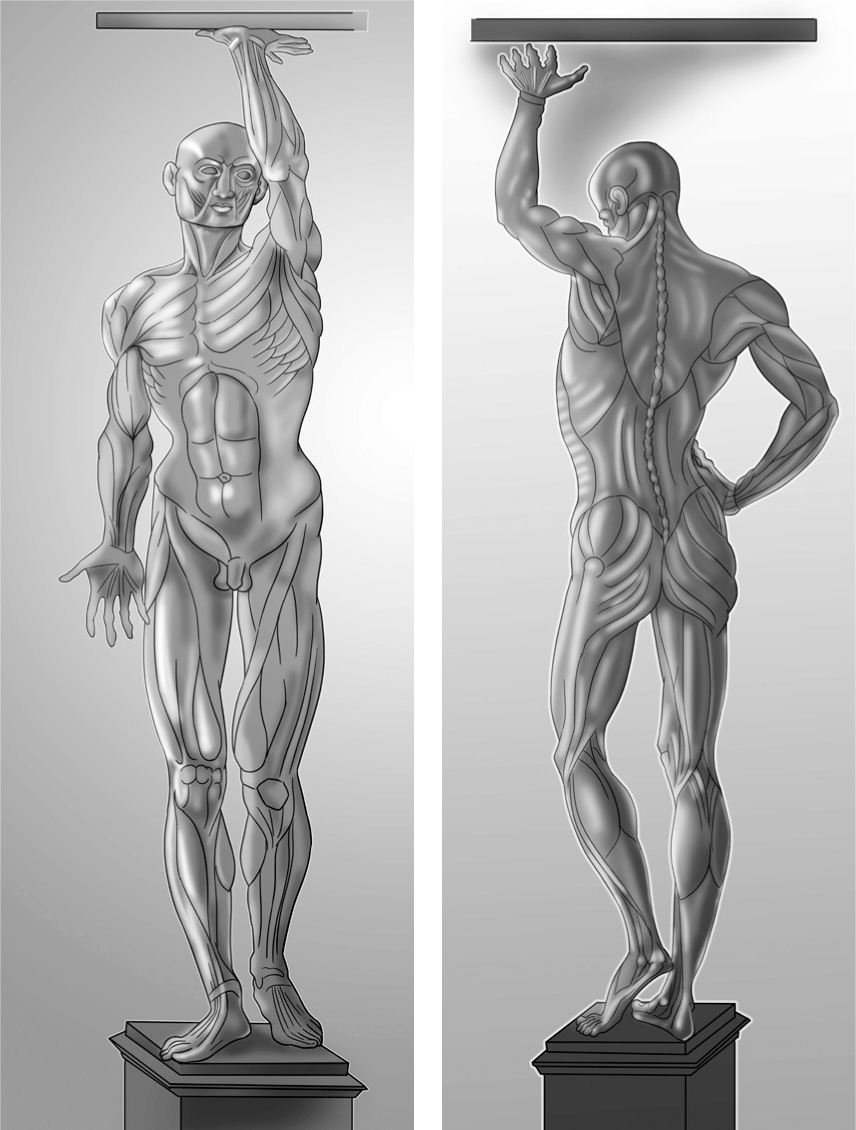

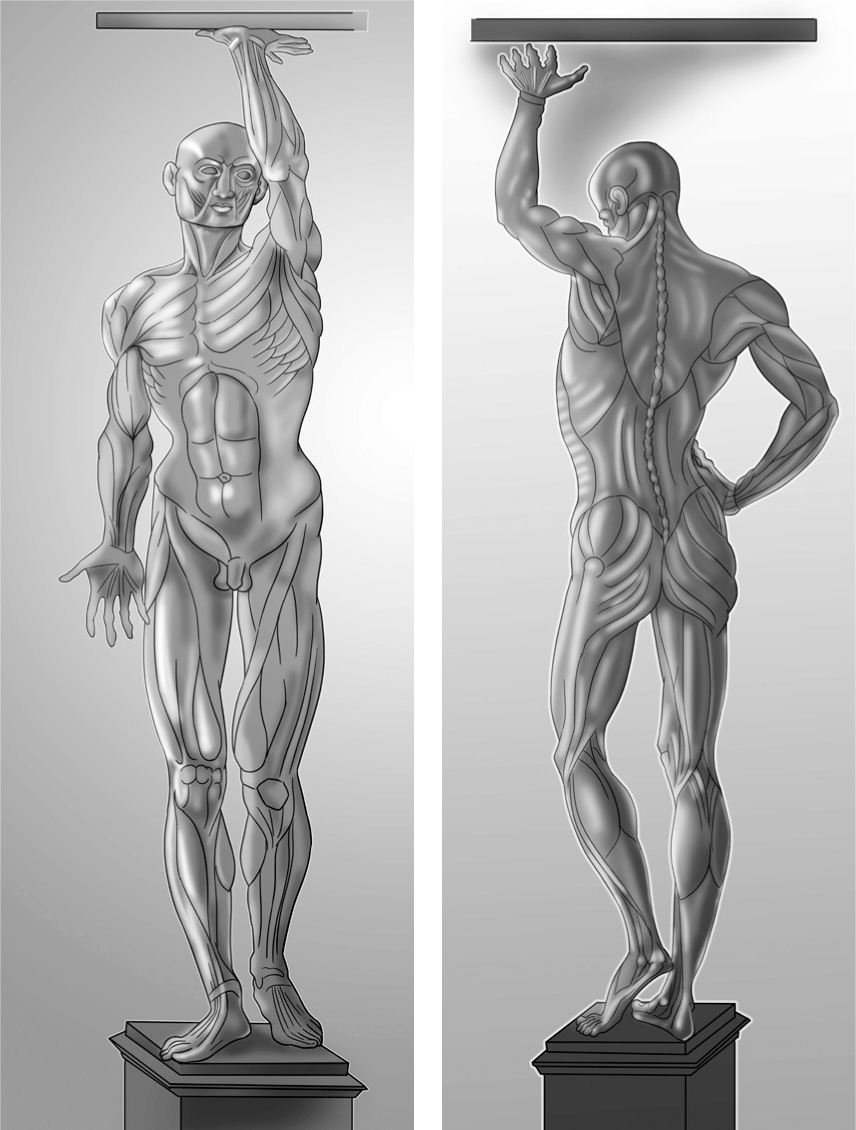

For a doctor with an antiquarian bent, the magnificent Anatomical Theatre of the University of Bologna is heaven, even on an Italian summers day, when the heat is unbearable and the wood-panelled hall effectively becomes a sauna. As I stood in the worlds oldest university, whose four-hundred-year-old hall is carved entirely out of spruce, I felt like a shrunken man exploring the interior of an ornate and antique jewellery box. In the middle of the room lies an imposing marble dissection table, which for centuries provided medical students occupying the wooden stalls of this academic arena with a full view of proceedings. The walls are decorated with large, intricately carved wooden sculptures of the ancient heroes of medicine. Hippocrates and Galen examine the students below with forbidding glares a look replicated by many subsequent medical school lecturers, no doubt. But, of all these wonders, the visitors eye is drawn to the centrepiece. Overlooking the whole theatre is the seat of the professor, covered by an elaborate wooden canopy held aloft by the magnificent Spellati: the Skinned Ones. These two statues, which take centre-stage at the altar to this church of medicine, are resplendent with exposed muscles, blood vessels and bones.

So-called corch figures (from the French for skinned) depict the muscles and bones of the body and their interplay, but without skin. These sinewy, skinless bodies have been synonymous with medicine since Leonardo da Vincis ground-breaking anatomical drawings of the fifteenth century, gracing the cover of almost every medical textbook. Peering up at the wooden corchs at the University of Bologna, it is clear to see that the skin despite being our largest and most visible organ, despite us seeing and touching it, indeed living in it, every moment of our lives is the organ most overlooked by the medical profession. Weighing nine kilograms and covering two square metres, skin wasnt even recognized as an organ until the eighteenth century. When we think of organs, or the human body at all, we rarely think of our skin. It is invisible in plain sight.

BOLOGNAS

SPELLATIWhen new acquaintances ask about my clinical and research interests, my almost apologetic response, that dermatology excites me, is usually met with confusion, pity, or a combination of the two. A close friend who is a surgeon likes to taunt me by saying, The skin is the wrapping paper that covers the presents. But part of what intrigues me is that, even though skin is the most observable part of our body, there is so much more to it than meets the eye.

My fascination with the skin started at the age of eighteen, on a slow afternoon two days after Christmas. My family had just made it through the last of the leftovers and I lay in a post-prandial sprawl on the sofa. Covered in blankets and revision notes, I sluggishly set about preparing for my first medical-school exam in a weeks time. I felt a bit grotty and my inner elbows and face were feeling unusually itchy. A later look in the mirror revealed that my cheeks had gone a darker shade of pink. Within a couple of days, my face and neck had become a red, dry, itchy mess. My friends and family offered tellingly different explanations, from exam stress and house allergens, to over-hot showers, skin microbes and eating too much sugar. Whatever the reason, after eighteen years of clear skin, it suddenly started to break down and eczema has shadowed me ever since.

Our skin is a beautiful mystery, cloaked in feelings, opinions and questions. The more science reveals of this terra incognita, the more we see that our most overlooked organ is actually our most fascinating. Skin is the Swiss Army knife of the organs, possessing a variety of functions unmatched by any other, from survival to social communication. Skin is both a barrier against the terrors of the outside world and with millions of nerve endings to help us feel our way through life a bridge into our very being. Simultaneously wall and window, our skin surrounds us physically, but it is also an exquisitely psychological and social part of our being. Our skin is not just a marvellous material; it is a lens through which we learn about the world and ourselves. Our physical skin teaches us to marvel at the intricacy of our bodies and the wonders of science. It teaches us to respect the millions of microbes that accompany us on our journey, to be sensible not radical about what we eat and drink, and to revere, but not fear, the sun. Our ageing skin directly confronts us with our own mortality. The mind-boggling sophistication of human touch invites us to re-examine the role of physical contact in an increasingly isolated and computerized society. There is no better platform than the psychological skin to show how our body and mind, and indeed our physical and mental health, are inextricably linked. Clothing, make-up, tattoos, societys heated dialogue on skin colour, and the judgement millions have suffered for skin deemed to be diseased or dirty, show that skin is our most social organ. Finally, ultimately, our skin transcends its physical presence and influences our faith, language and thinking.

Next page

BOLOGNAS SPELLATI

BOLOGNAS SPELLATI