FOREWORD

W hen I got my degree at the University of Berlin, almost eighty years ago, biology consisted of two branches, zoology and botany. What dealt with animals was zoology, and everything else, including fungi and bacteria, was assigned to botany. Things have improved since then, particularly since the discovery of the usefulness of yeast and bacteria for molecular studies. Most of these studies, however, strengthened the reductionist approach and thus fostered a neglect of the major actors in evolutionindividuals, populations, species, and their interactions.

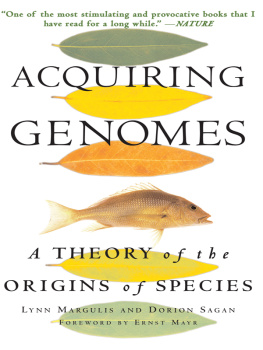

The authors of Acquiring Genomes counter this tendency by showing the overwhelming importance of interactions between individuals of different species. Much advance in evolution is due to the establishment of consortia between two organisms with entirely different genomes. Ecologists have barely begun to describe these interactions.

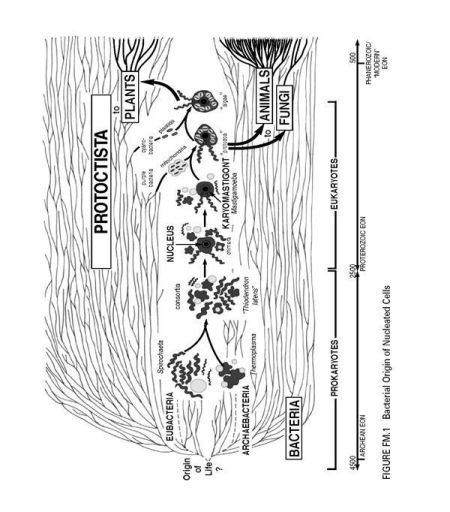

Among the millions of possible interactions (including parasitism), the authors have selected one as the principal object of their book: symbiosis. This is the name for mutual interaction involving physical association between differently named organisms. The classical examples of symbiosis are the lichens, in which a fungus is associated with an alga or a cyanobacterium. At first considered quite exceptional, symbiosis was eventually discovered to be almost universal. The microbes that live in a special stomach of the cow, for instance, and provide the enzymes for its digestion of cellulose are symbionts of the cow. Lynn Margulis has long been a leading student of symbiosis. She convinced the cytologists that mitochondria are symbionts in both plant and animal cells, as are chloroplasts in plant cells. The establishment of a new form from such symbiosis is known as symbiogenesis.

For many years, Margulis has been a leader in the interpretation of evolutionary entities as the products of symbiogenesis. The most startling (and, for some people, still unbelievable) such event was the origin of the eukaryotes by the fusion of an archaebacterium with some eubacteria. Both partners contributed important physiological capacities, from which ensued the great evolutionary success of the eukaryotesthe cells from which all animals, plants, and fungi are made.

Symbiogenesis is the major theme of this book. The authors show convincingly that an unexpectedly large proportion of evolutionary lineages had their origins in symbiogenesis. In these cases a combination of two totally different genomes form a symbiotic consortium which becomes the target of selection as a single entity. By the mutual stability of the relationship, symbiosis differs from other cases of interaction such as carnivory, herbivory, and parasitism.

The acquisition of a new genome may be as instantaneous as a chromosomal event that leads to polyploidy. The authors lead one to suggest that such an event might be in conflict with Darwins principle of gradual evolution. Actually, the incorporation of a new genome is probably a very slow process extending over very many generations. But even if instantaneous, it will not be any more saltational than any event leading to polyploidy.

The authors refer to the act of symbiogenesis as an instance of speciation. Some of their statements might lead an uninformed reader to the erroneous conclusion that speciation is always due to symbiogenesis. This is not the case. Speciationthe multiplication of speciesand symbiogenesis are two independent, superimposed processes. There is no indication that any of the 10,000 species of birds or the 4,500 species of mammals originated by symbiogenesis.

Another of the authors evolutionary interpretations is vulnerable as well. They suggest that the incorporation of new genomes in cases of symbiogenesis restores the validity of the time-honored principle of inheritance of acquired characters (what is called Lamarckian inheritance). This is not true. The two processes are entirely different. Lamarckian inheritance is the inheritance of modified phenotypes, while symbiogenesis involves the inheritance of incorporated parts of genomes.