ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editors express their special thanks to the following people and institutions who have helped make this project a pleasure.

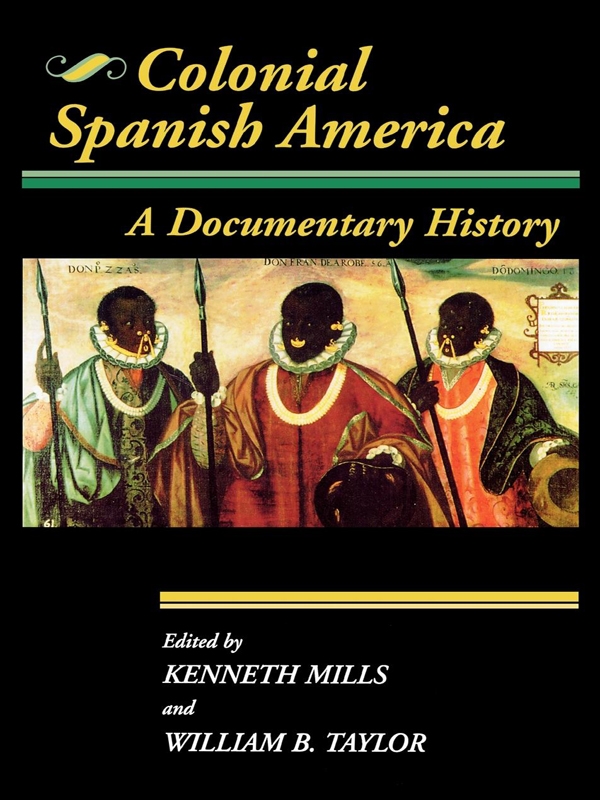

William Taylor is indebted to E. William Jowdy for his generous interest and bracing criticism of many introductions to selections. He also thanks Thomas B. F. Cummins for collaborating on short notice in an appraisal of the enigmatic portrait of the three gentlemen from Esmeraldas; Karin E. Taylor for redrawing the plan of the Huejotzingo altarpiece and sending her father off to read ltalo Calvino; Daniel Slive for advice about colonial engravings; and James Early for sharing slides from his splendid collection on colonial Mexican architecture. The Edmund and Louise Kahn Chair fund at Southern Methodist University helped cover editorial costs.

Kenneth Mills thanks Roger Highfield for the way he speaks about the place of primary sources in teaching and David Church Johnson for his teaching in practice; Elizabeth Mills for her timely criticism and suggestions; Peter Lake for his comments on a few of the selections used in our comparative seminar; and Peter Brown, Robert Connor, and J. Paul Hunter, among others, for advice and encouragement along the way. He is grateful for support of this project from the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, as well as the University Committee for Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences, the Program in Latin American Studies, and the Department of History, all at Princeton University.

John Blazejewski, Richard Hurley, and Andrew Reisberg expertly photographed the previously published images. Margaret Case read a late version of the manuscript, and her careful and creative eye, along with the expertise of Linda Pote Musumeci of Scholarly Resources, did much to establish its final form. Finally, both editors want to acknowledge the students in their respective classes who, usually without knowing it, have partaken of a number of teaching experiments and contributed both to what appears in, and what has been shed from, this book.

NOTES ON SELECTIONS AND SOURCES

- Selection 1 is excerpted from The Huarochir Manuscript: A Testament of Ancient and Colonial Andean Religion, edited and translated from the Quechua by Frank Salomon and George L. Urioste, 1991 (Austin, 1991), pp. 41-54. Courtesy of the authors and the University of Texas Press. Readers wanting more of this source are encouraged to consult the paperback edition noted above and Salomons fine introductory essay, which informs the present introduction. On the context out of which the document derives, see especially Karen Spalding, Huarochir: An Andean Society under Inca and Spanish Rule (Stanford, 1984); and the interpretation of Antonio Acosta Rodriguez, Francisco de Avila, Cusco 1573(?)-Lima 1647, in Ritos y tradiciones de Huarochir: Manuscrito quechua de comienzos del siglo XVII, edited and translated by Gerald Taylor (Lima, 1987), pp. 551-616.

- Our opening to discussion of the two tunics in is the so-called Poli uncu from the Poli collection in Lima, Peru (Andrien and Adorno, 176, 10b) .

- This selection is translated from Bernardino de Sahagn, Coloquios y doctrina cristiana, edited by Miguel Len-Portilla (Mexico, 1986), fols. 34r, 35r, 36r, and 37r (facsimile), pp. 8689 (Spanish transcription). Courtesy of the Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico.

- Much of the discussion for Selection 4 is adapted from Richard F. Townsend, State and Cosmos in the Art of Tenochtitlan (Washington, DC, 1979), pp. 6370. The photograph of the stone () is taken from Antonio de Len y Gama, Descripcin histrica y cronolgica de las dos piedras... , 2d ed. (Mexico, 1832), plate 2.

- Selection 5 is excerpted from Christians and Moors in Spain (Warminster, Eng., 1992), vol. 3, Arabic Sources (7111501), edited and translated from the Arabic by Charles Melville and Ahmad Ubaydli, pp. 2831, 5255, and 11015. Courtesy of Aris and Phillips, Warminster, Wiltshire, England. Melvilles and Ubaydlis short introductions to these texts inform our own, as does their glossary on religious and legal terminology. Also of particular help has been the approach to convivencia in the work of Thomas F. Glick, as well as recent formulations on the interdependence of violence and tolerance in related settings by David Nirenberg in Communities of Violence: Persecution of Minorities in the Middle Ages (Princeton, 1996). Amrico Castros Espaa en su historia: Cristianos, moros y judios (Buenos Aires,1948), with modifications and additions, exists in an English translation by Edmund L. King, The Structure of Spanish History (Princeton, 1954).

- Olivia Harriss essay was first published in the Bulletin of Latin American Research 14:1 (1995): 924. Notes have been omitted. 1994, Society for Latin American Studies. Reprinted courtesy of Elsevier Science Ltd., Oxford, England.

- This translation first appeared as the first part of Appendix 1 in The Oroz Codex: The Oroz Relacin, or Relation of the Description of the Holy Gospel Province in New Spain, and the Lives of the Founders and Other Noteworthy Men of Said Province, Composed by Fray Pedro Oroz [15841586], translated and edited by Angelico Chvez, O.F.M. (Washington, DC, 1972), pp. 34753. Courtesy of the Academy of American Franciscan History.

- Selection 8, an extract from an anonymous original manuscript in the collection of the Biblioteca de Palacio in Madrid, is excerpted from Francisco de Vitoria, Political Writings, edited by Anthony Pagden and translated by Jeremy Lawrance (Cambridge, Eng., 1991), Appendix B, Lecture on the Evangelization of Unbelievers, pp. 34151. Courtesy of Cambridge University Press. Our introduction to this reading is assisted especially by Pagdens Introduction, pp. xiiixxviii; Lawrances Biographical Notes and Glossary, pp. 35381; and Quentin Skinner, The Foundations of Modern Political Thought, vol. 2, The Age of Reformation (Cambridge, Eng., 1978), pp. 13573.

- , is in the collections of the British Library in London. The letter is reproduced in facsimile in Americus Vespucius, The First Four Voyages of Americus Vespucius: A Reprint in Exact Facsimile of the German Edition Printed at Strassburg, by John Grninger, in 1509, with a prefatory note by Luther S. Livingston (New York, 1902). Among numerous English translations are The First Four Voyages of Amerigo Vespucci translated from the rare original edition (Florence, 15056); with some Preliminary Notices, by M. K., edited and translated by Michael Kerney (London, 1885); and Letters from a New World: Amerigo Vespuccis Discovery of America, edited and translated by Luciano Formisano (New York, 1992), pp. 5797.

The circuitous path of Vespuccis letter to Soderini, even within the confines of the five years after it was written, tells us something of the diffusion and reproduction of documents and books of great interest in contemporary western Europe. The original Italian Lettera di Amerigo Vespucci delle isole nuovamente trovate in quattro suoi viaggi was written by Vespucci in Portugal on September 4, 1504. It was carried to Soderini in Florence by one of Vespuccis fellow seamen and published there. The publication bears no date, but it was probably printed in 1505 or 1506. The letter found its way to France and was first translated into French by an unknown hand in saint-Di in Lorraine, and this version has never been found. But from it, Jean Basin de Sendacour, a member of the college at saint- Di and one of a group who had just set up a printing press, made a Latin translation. The letter from Vespucius was published in 1507 at saint-Di as an appendix to the Cosmographi Introductio by Martin Waldseemller (14701521?), and it was in Waldseemllers book that America was suggested as the proper name for the new lands beyond the Ocean Sea. The German translation of the Grninger edition, of which these two images were a part, was thus made from a Latin edition, which itself was translated from a lost French translation of the Italian original.