The ancient cultures of Mexico along with the Maya civilization comprise the larger entity known to archaeologists as Mesoamerica, a name first proposed by the anthropologist Paul Kirchhoff and including much of the great constriction that separates the masses of North and South America. Above all, the peoples of Mesoamerica were farmers, and had been somewhat isolated for thousands of years from the simpler cultivating societies of the American Southwest and Southeast by the desert wastes of northern Mexico, through which only semi-nomadic, hunting aborigines ranged in pre-Spanish times. Beyond the southeastern borders of Mesoamerica lay the petty chiefdoms of lower Central America, distinguished by a high production of fine ceramics and quantities of jade or gold ornaments, lavishly heaped in the tombs of their great chieftains.

Further south yet, in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, was the Andean area, most noted for its final glory, the immense Inca empire, but having native civilizations as far back in time as the tenth century before Christ, and large temple constructions even earlier than that. The Andean area and Mesoamerica were the twin peaks of American Indian cultural development, from which much else in the Western Hemisphere seems both peripheral and sometimes derived; yet this picture may be oversimplified, because research in the Pacific lowlands of Ecuador, the Caribbean coast of Colombia, and the upper reaches of the Amazon has shown that the important criteria of settled life agriculture, pottery, and villages may have had a precocious start in those areas.

Setting them off from the rest of the New World, the diverse cultures of Mesoamerica shared in a number of features most of which were pretty much confined to their area. The most distinctive of these is a complicated calendar based upon the permutation of a 260-day sacred cycle with the solar year of 365 days. Others are hieroglyphic writing (the Andean area never developed a script); bark-paper or deer-skin books which fold like screens; maps; an extensive knowledge and use of astronomy; a team game resembling basketball played in a special court with a solid rubber ball; large, well-organized markets and favored ports of trade; chocolate beans as money and as the source of a drink; wars for the purpose of securing sacrificial victims; private confession, and penance by drawing blood from the ears, tongue, or penis; and a pantheon of extraordinary complexity.

1 Map of major topographical features of Mexico.

Naturally, the peoples of Mesoamerica followed a number of other customs which are widespread among New World Indians, such as ceremonial tobacco smoking, but their typical method of food preparation as a unified complex appears to be unique. The basis of the diet was the four-some of maize, beans, squash, and chile peppers. Maize was, and still is, prepared by boiling it with lime, then grinding the swollen kernels with a hand stone (Spanish mano) on a trough- or saddle-shaped quern (metate, from the Nahuatl metlatl). The resulting dough is either toasted as flat cakes known in Spanish as tortillas, or else steamed or boiled as tamales. Always and everywhere in Mesoamerica, the hearth comprises three stones, and being the conceptual center of the world, is semi-sacred.

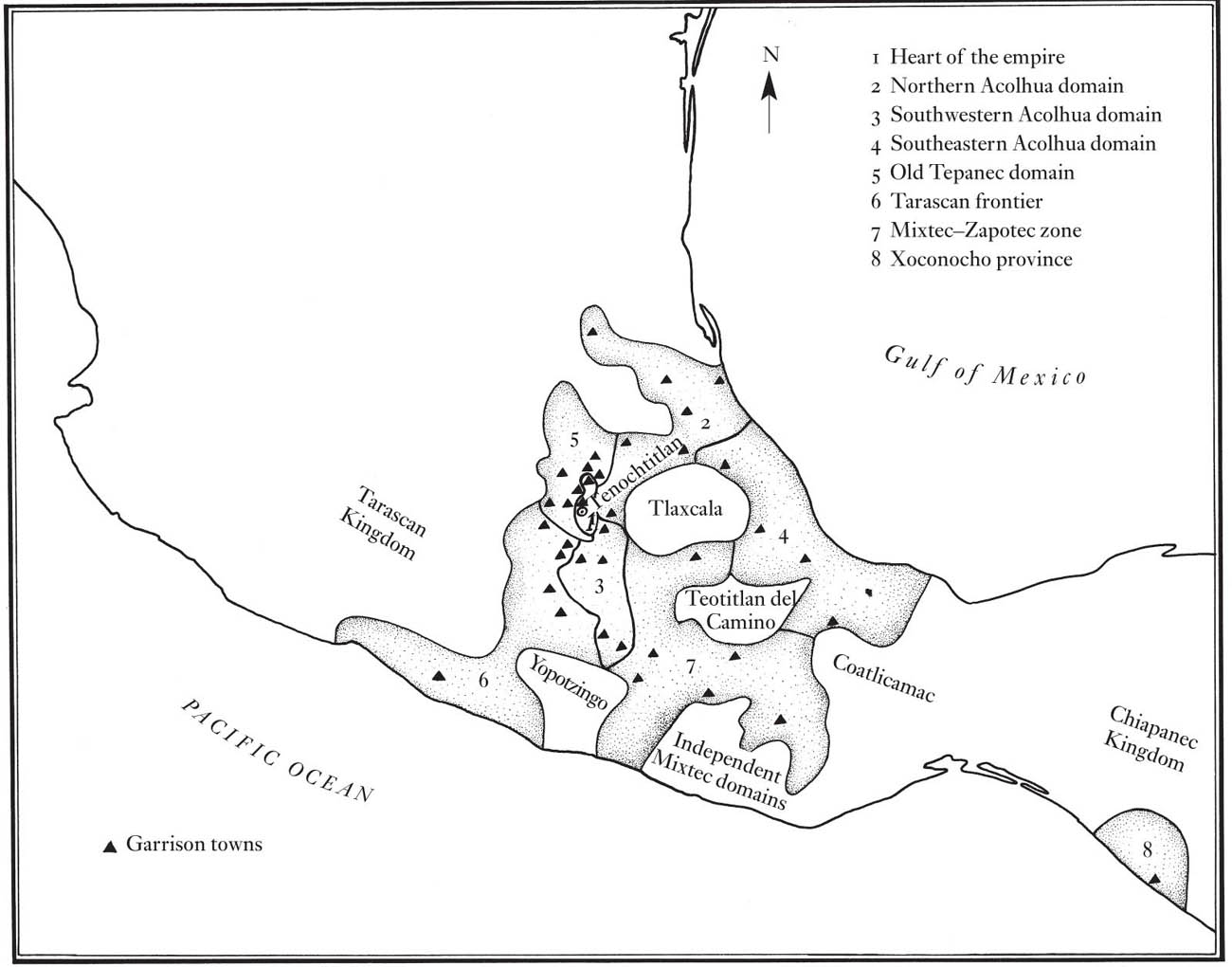

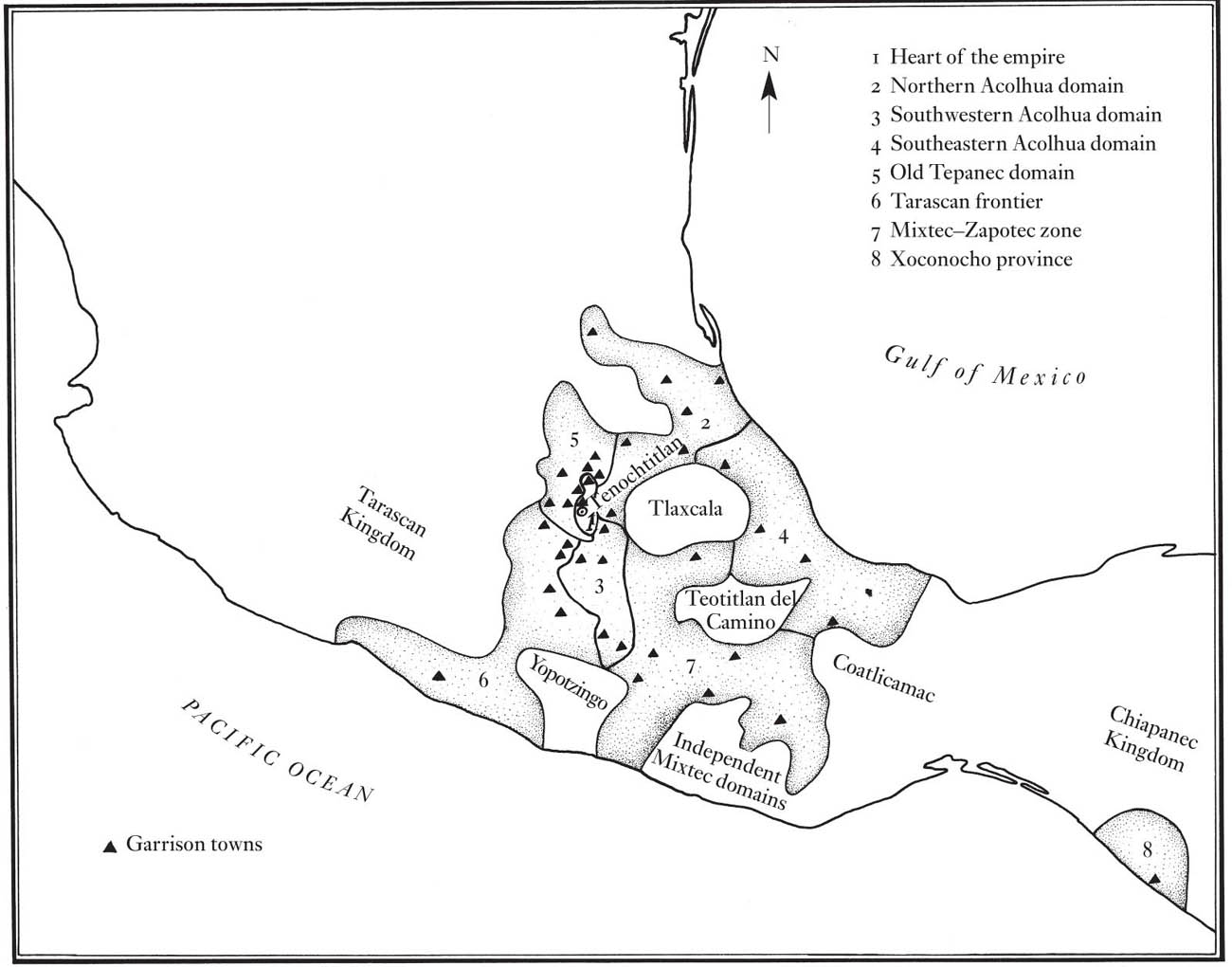

On the map, Mexico resembles a great funnel, or rather, a cornucopia, with its widest part toward the north and its smallest end twisting to the south and east, meeting there the sudden expansion of the Maya area. There are few regions in the world with such a diverse geography as we find within this area Mexico is not one, but many countries. All the climatic extremes of our globe are found, from arctic cold near the summits of the highest volcanoes to the Turkish-bath atmosphere of the coastal jungles. Merely to pass from one valley to another is to enter a markedly different ecological zone.

This variation would be of interest only to the tourist agencies if one neglected to consider the effect of these contrasts upon the human occupation of Mexico. A topsy-turvy landscape of this sort means a similar diversity of natural and cultivated products from region to region above all, different crops with different harvest times. It means that no one region is now, or was in the past, truly self-sufficient. From the most remote antiquity, there has been an organic interdependence of one zone with the others, of one people or nation with all the rest. Thus, no matter how heterogeneous their languages or civilizations, the people of Mexico, through exchange of products, were bound up with each other symbiotically into a single line of development; for this reason, great new advances were registered throughout the land within quite brief intervals of time.

Most of this funnel-shaped country lies above 3,000 ft (900 m), with really very little flat land. The Mexican highlands, our major concern in this book, are shaped by the mountain chains that swing down from the north, by the uplands between them, and by numerous volcanoes which have raised their peaks in fairly recent geological times. The western chain, the Sierra Madre Occidental, is the loftiest and broadest of these, being an extension of the Rocky Mountains; it and the Sierra Madre Oriental to the east enclose between their pine-clad ranges an immense inland plateau which is covered by mesquite-studded grasslands and occasionally even approaches true desert. Effectively outside the limits of Mesoamerican farming, the Mexican plateau was the homeland of partially or wholly nomadic hunters and collectors. As we move south, the two Sierras gradually approach each other until the interior wastelands terminate some 300 miles (480 km) north of the Valley of Mexico.

2 Central highlands of Mexico, near Puebla, with Popocatepetl volcano in the distance.

The Valley of Mexico, the center of the Aztec empire, is one of a number of natural basins in the midst of the Volcanic Cordillera, an extensive region of intense volcanism and frequent earthquakes. A mile and a half high with an area of 3,000 sq. miles (7,800 sq. km), much of the Valley was once covered by a shallow lake of roughly figure-eight shape, now largely disappeared through ill-advised drainage and the general desiccation of central Mexico in post-Conquest times. Since the Valley of Mexico has no natural outlet, changing rainfall patterns have produced severe fluctuations in the extent of the lake. As will be seen in , the Aztec table was amply supplied by foods raised on its swampy margins in the misnamed floating gardens, or chinampas. Surrounded by hills on all sides, the Valley is dominated on the southeast by the snowy summits of the volcanoes Popocatepetl (Smoking Mountain) and Iztaccihuatl (The White Lady).

3 Chinampas or floating gardens in the vicinity of Xochimilco, Valley of Mexico.

Other important sections of the highlands are the Sierra Madre del Sur, its steep escarpment fronting the Pacific shoreline in southern Mexico, and the mountainous uplands of Oaxaca; both of these fuse to form a highland mass heavily dissected into countless valleys and ranges. Separated from this difficult country by the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the southeastern highlands form a continuous series of ranges from Chiapas down through Maya territory into lower Central America.

Next page