Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Foreword

Evolution Through Inebriation?

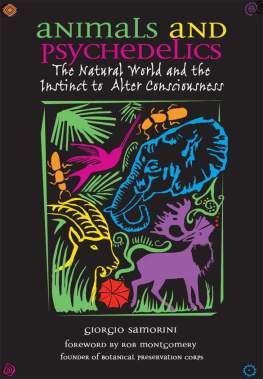

T hat animals drug themselves is a deceptively simple statement. Contained within it, as within the pages of this remarkable book, is nothing short of a radical reexamination of what it is to be human. The consequences of this simple truth are both far reaching and immediate.

Lets begin by breaking this concept down into two aspects: first, that animals do drug themselves as a nonartificial impulse and second, that they do so intentionally. That they drug themselves requires drawing upon the comparatively precise sciences of botany, chemistry, and pharmacology to discover what exactly are the drug sources, their composition, and their activity. That animals drug themselves raises a different order of consideration. This involves the scientific study of animal behavior, or ethology. Although it may be possible to know through behavioral observation whether an animal is intoxicated or not, and by what means, some of the more subtleand therefore most intriguingtypes of altered states and inebriation can be difficult to discern. Much less can be understood about the nature of that animals felt experience, let alone what the individuals motivation might be for consuming the drug. This field of study, however, promises such fascinating and crucial insights into the nature of consciousness that we are compelled to explore it with every resource available. The results will surprise you.

We all are familiar with neighborhood cats indulging themselves with garden catnip, and many know about the pet monkeys that enjoy smoking tobacco cigarettes. Most of us have heard of animals in cruel laboratory research clinics self-administering drugs such as cocaine. We can even conjure images of animals, on their own, unwittingly consuming fermented fruits or psychoactive plants and experiencing accidental intoxication. But how many of us realize thatentirely on their own and without the influence of captivity or conditioningwild animals, birds, and even insects do indeed drug themselves? This deliberate seeking of inebriation among all classes of animals is a perfectly natural, normative behavior. Indeed, the pursuit of inebriation has been proposed as a kind of fourth driveakin to hunger, thirst, and sexso ubiquitous is its manifestation.

Animals engage in intoxicating drug consumption. This fact forms one of the most provocative and original of Giorgio Samorinis insights: this moment of drug-induced inebriation produces a deschematizzazione, or deconditioning, that allows for new behavioral ways to be established in a species. This prefaces the long-established discovery by R. Gordon Wasson and successive others, that consciousness-expanding plants and mushrooms are key to the origins of humanity itself and the inspiration for religious thought, influencing humanity since remotest history through the present and surely into our future. Before taking this conceptual leap from the influence of psychoactive drugs on human culture to their influence on species evolution, we must ask what distinguishes human from animal awareness, and is it such a great distinction at all?

Ethology is the science of animal behavior, ethnobotany studies human uses for plants, and ethnopharmacognosy is the science of human use of drug plants. Ethnozopharmacognosy is the study of mans use of animals as medicinesbugs as drugs. Drugs of animal origin include serum vaccines, hormones, aphrodisiac beetles (spanish fly), immunostimulating ants, cod liver oil, deer musk, cat civet, psychoactive toad venoms, dream fish, and toxic honeys. These are things that people use. Animals also seek out drugs in their environment for medicinal use, such as purgative grasses. We have learned to observe these animal uses of healing plants for our own drug discovery, and indeed this may be how we humans developed most of our medicinal repertoire.

A further subdiscipline of ethnobotany is the study of psychoactive plant use, sometimes called entheobotany. Giorgio Samorini estimates that there are nearly 200 scientific researchers devoted to this emerging field of entheobotany, and among us, even fewer investigators of entheozopharmacognosy, or the use by humans of inebriating animal products. It follows that there is also a study of the use of psychoactive substances by animals. Yet there is currently no name for this line of study andalthough it may be fun to create onethis lack of terminology is indicative of the appalling absence of scientific research in this area.

Animals do use drugs, and within this new study of animals medicating themselves exists the sphere that is the intriguing subject of this book: animals intentionally inebriate themselves. This book addresses the fact that animals drug themselves for more than medicinal purposes; they drug themselves for inebriation. Animals use drugs, and animals drug themselves.

As this book reveals, the occurrence of animals inebriating themselves is present throughout all levels of the animal worldpresent, but scattered. Within any species, inebriation-seeking behavior is not shared by all individuals. There may be a rather constant percentage of individualsanimals, birds, insects, and humansfor whom inebriation is a sought-after experience, an intentional impulse. It is not for everyone, so to speak, but there are positive indications that this special, altered minority contributes something beneficial for the ongoing development and adaptation of its species.

Could it be that animals that consume various plant inebriants develop enhanced senses and perceptual acuity that confer an adaptive advantage in evolution? Even strict biologists agree that behaviors leading to more successful food acquisition or hunting techniques increase survival. Suggestive evidence shows that altered states produced by certain psychoactive plants can allow rigid instincts to be bypassed, enabling new behaviors and techniques to be learned and passed along by the experimentalists of a species. Awareness-enhancing plant drugs are indeed sought out by certain animals. And behavior which increases mating, such as eating prosexual or libidostimulant plant drugs (the so-called aphrodisiacs), means disproportionate breeding by that savvy individual who thus breeds more of its gene type into the species.

Consider some of the latest discoveries in this ongoing study. Wild chimpanzees in the rainforests of tropical West Africa have been observed intentionally using medicinal plants, which these chimps seem to apply as effective antiparasitics. This chimp herbalist subculture must have developed long, long ago. Its documentation by Professor Michael Huffman of Kyoto Universitys Primate Research Institute is having tremendous impact on our understanding of these primates. Even more startling is Dr. Huffmans discovery of the recreational use of the drug plants for inebriationAlchornea floribunda by gorillas and A.cordifolia by chimpanzeesas published in the journal African Studies Monographs, Winter 2002. A. floribunda is the source of the plant drug aln, a visionary intoxicant and aphrodisiac used by West African cults. Local people claim to have discovered these uses by observing gorillas become inebriated after eating the roots. The same is said by native Africans of the more widely known eboka,

Next page