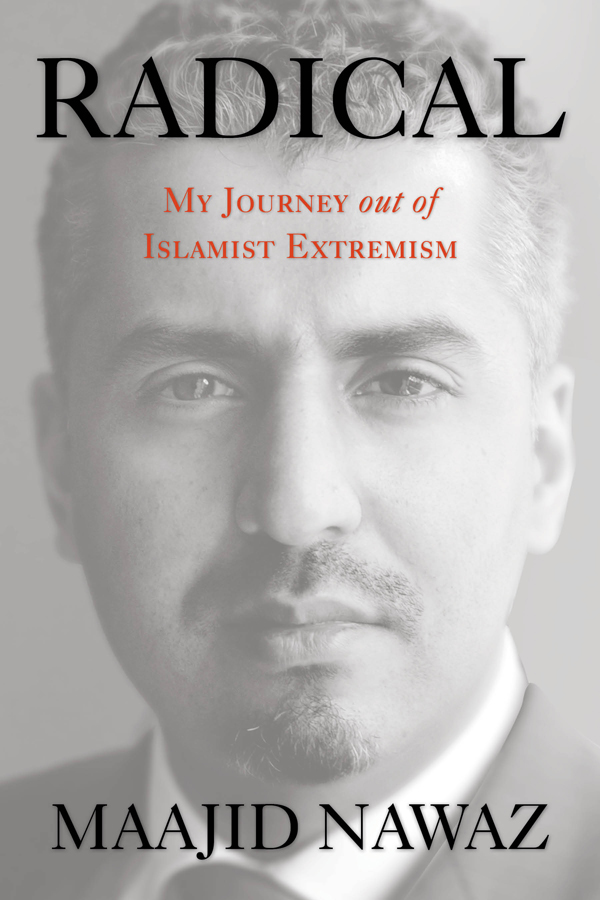

R ADICAL

R ADICAL

My Journey out of Islamist Extremism

M AAJID N AWAZ

WITH T OM B ROMLEY

Copyright 2013 by Maajid Nawaz

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout artist: Melissa Evarts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nawaz, Maajid.

Radical : my journey out of Islamist extremism / Maajid Nawaz ; with Tom Bromley.

pages cm

E- ISBN 978-0-7627-9551-2

1. Nawaz, Maajid. 2. MuslimsGreat BritainBiography. 3. ExtremistsGreat BritainBiography. 4. Islamic fundamentalismGreat Britain. I. Title.

BP166.14.F85N38 2013

297.092dc23

[B]

2013017848

For my family, my son, and for all my friends.

And for those with whom I started a movement.

The moving finger writes, and having written moves on.

Nor all thy piety nor all thy wit, can cancel half a line of it.

O MAR K HAYYAM, R UBAIYAT

C ONTENTS

P REFACE TO THE US E DITION

Being American

If there is one identity today that is as misunderstood as being Muslim, let that be the American identity. And just as few religions are as mischaracterized by Americans today as Islam, few other groups mischaracterize America today as much as the worlds Muslims. Matters, to put it quite simply, have come to a head. Radical, as well as being a factual and candid account of my life thus far, is an act of diplomacy dressed in the disguise of storytelling.

The story in this book is one of a Western-born Muslim who first found his voice of rebellion through a heady diet of American hip-hop, graffiti, and dance. The first part of Radical tracks my conversion from B-boy to Islamistthe gradual yet complete ideological transformation of a disillusioned young British teenager to a hardened Islamist recruiter. I came to liveand was prepared to dieto counter what I saw as American hegemony on a global scale.

In righteous indignation I traveled to four different countries to seed my divisive Islamist message, casting America as the enemy of my people. Fusing faith with fury, I dedicated my entire youth to awakening what we called the sleeping giantrousing the worlds 1.5 billion Muslims against the USA. My charge was halted only upon my 2002 incarceration in Egypt for inciting Egyptians against Hosni Mubaraks US-allied dictatorial regime. Id never wanted vengeance more than during those first few days following our arrest. Id never felt more violent than those few days immediately after our torture. But mine was exactly the sort of mind, or more accurately the sort of heart, that America needs to hear from now. Radical addresses the reader in the voice of that young man, bringing the reader as close to his heartacross time and distanceas is possible through the medium of prose.

Despite my aggressively anti-West stance, it was, ironically, American subculture (through hip-hop) that first lent me a voice, first taught me to rebel, and first inspired in me a sense of self-worth. While this was totally lost on me at the time, I owe my very political awakening to America. It was American subculture that laid the foundations for me to reject the West entirelyand this too was done through an entirely Western discourse.

In this way, I have come to believe that a strange fetish exists between the hater and the hated. It is a relationship that the hater will do everything in vain to deny, yet one he cannot quite shed. It is also a relationship that the object of hate will act incredulous to, yet cannot quite help but to douse with fuel on occasion. And what was lost upon us all was that by defining ourselves against something, we were in fact defining ourselves by it.

The ideology of Islamism could have benefited greatly from this insightthat it was born, and flourished, in this hatred of the other. During my time in Cairos Mazrah Tora prison, I happened to share a cell block with the current global leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, Dr. Muhammad Badee. In a poetic twist of fate reminiscent of Josephs rise to power after his own imprisonment in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood now rules Egypt while the former dictator Hosni Mubarak is held in that very same prison.

During our prison years Dr. Badee and I struck up a friendship. He told me that it was he who had originally smuggled Sayyid Qutbs Islamist manifesto Milestones out from that very prison to the wider public in the early 1960s. Qutb was the founding father of modern-day, militant Islamism, otherwise known as Jihadism. Qutb was eventually executed by Egyptian president Gamal Abd al-Nasser in 1966, but the Islamist ideology of Milestones outlasted the legacy of Nassers Pan-Arabism, going on to inspire hundreds of thousands of Islamists the world over. It directly inspired bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, who used Milestones to form the philosophical foundations of al-Qaeda.

Qutbs journey toward a more aggressive, anti-American dogma in fact began after his two-year sabbatical to 1940s America. How ironic, the history of Islamist vitriol was inextricably linked to the object of our hatethe USA. Some of the most influential figures in our ideological journey had defined themselves against America. It was as if she were a fraternal twin, one whom we hated yet had no choice but to acknowledge. In this way, America has a curious history with Muslim extremism. From the reverse racism of Malcolm Xs early days in the Nation of Islam (a movement thatthrough Public Enemyinspired me during my teenage years) to Qutb and Islamism, America had inadvertently bred her own worst enemies, her strongest codependents.

Qutb was so disillusioned by his own inability to integrate with 1940s America, and presumably hurt by the common assumption that he was African American, that it seems to have inspired within him deep shame and embarrassment, provoking in him the crudest of prejudice. After this trip, which included time at Stanford University, Qutb returned to Egypt and published The America that I Saw, an exercise in blind bigotry the likes of which would make even todays most committed Islamists cringe:

The American appears to be so primitive in his outlook on life and its humanitarian aspects that it is puzzling to the observer... a primitiveness that reminds one of the days when man lived in jungles and caves.

Its astonishing to read this from someone with an otherwise keen mind. Qutb vented against the racism he experienced in 1940s America without it occurring to him once that he was playing into this very same, and rather ignoble, racial stereotyping:

The American is primitive in his artistic taste, both in what he enjoys as art and in his own artistic works. Jazz music is his music of choice. This is that music that the Negroes invented to satisfy their primitive inclinations, as well as their desire to be noisy on the one hand and to excite bestial tendencies on the other. The Americans intoxication by jazz music does not reach its full completion until the music is accompanied by singing that is just as coarse and obnoxious as the music itself.

The book was a bigoted tour de force on everything from American mens hairstyles and their proclivity for developing oxen arm muscles, to the nature of American women: