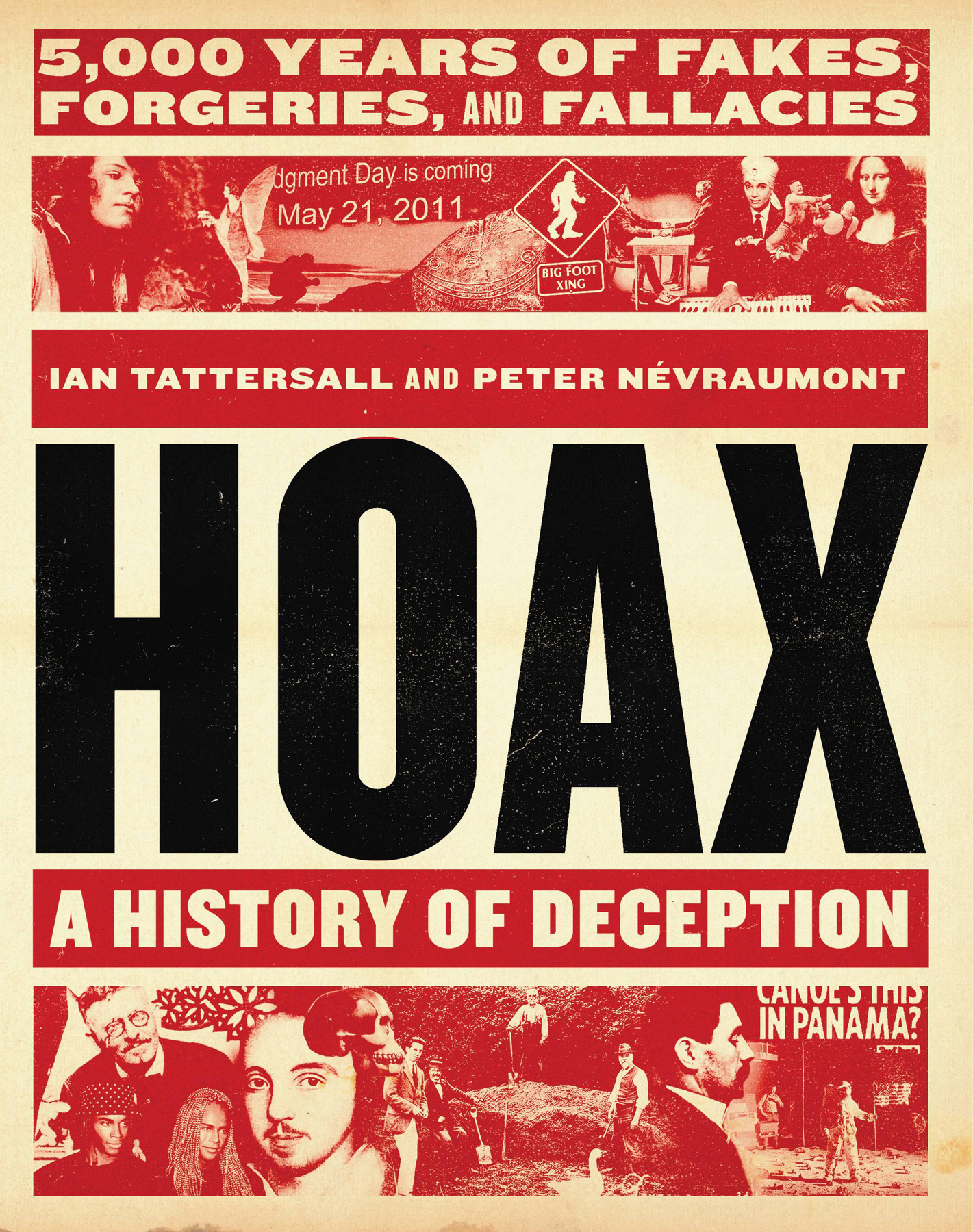

T he human condition has always eluded accurate description. At the extremes, people may be monsters or saints. They may be miserly or munificent. Decorous or crude. Brilliant or dumb. But while these wilder manifestations of human behavior tend to be the ones that grab our attention, most of the time we find ourselves somewhere in the middle of any behavioral spectrum you might want to consider.

It is mostly in this gray, ambiguous area of human experience that charlatanism, fraud, and fakery have flourished, doubtless ever since Homo sapiens emerged in its modern form around a hundred thousand years ago. In many ways, what has happened over the ages in this vast, equivocal middle ground of human experience tells us a lot more about our predecessorsand our ownlives than many of the grander events we usually think of as history do; and certainly, no account of our historical soap opera is complete that does not consider this aspect of the human condition.

The tendency that has made this vast swamp of morally dubious incidents possible is pretty familiar and straightforward. No con artist is unaware of how credulous his fellow citizens tend to be, evenor perhaps especiallythose who think themselves most highly sophisticated. And every trickster is acutely conscious of the seemingly universal penchant for believing what one wants to hear. Either of these basic human proclivities opens the door for the unscrupulous to exploit their less cynical peers.

In 1165, the Byzantine emperor Manuel Comnenus received a letter from an unknown Christian king, Prester John, whose lands allegedly extended beyond India to the Tower of Babel. Pope Alexander III then sent envoys east, hoping that Prester John would come to the aid of Crusaders in Jerusalem besieged by Muslim armies. Prester Johns mythical kingdom, as seen on this 1564 map, became the object of a quest that fired the imaginations of generations of adventurers, but has always remained out of reach.

In contrast, the motivations that have fueled the consequent entrenchment of misrepresentation, fakery, and demagoguery in common human experience are a little more complex; and they are as varied as the species Homo sapiens itself. The reason for taking advantage of the innocence, avarice, or preconceptions of others is most commonly simple greed, but malice and personal animosity are also frequent driving forces, as are sheer impishness, the desire for power or influence, a wish to show the experts, or even the pathetic need to simply be recognized for something.

Still, wherever the incentive may come from in any particular case, the dynamic that makes fraud possible is evidently baked hard into that frustratingly elusive human condition. As long as there are people and language there will be frauds and lies, con artists and suckers, the credulous and their gleeful exploiters.

If both human unwariness and the desire to take advantage of it areand always have beenirredeemably part of the human psyche, then the consequent hoaxes, frauds, and fallacies also provide us with an alternative lens through which to view the vagaries of the past and present. This lens is potentially a powerful one, for while human gullibility is eternal, its expression varies hugely according to the fears, aspirations, and world views of each generation. At the very least, we can confidently claim that what we recount here is not history as written by the victors.

In this book, merely the most recent expression of a splendid historical tradition that dates back at least to Charles MacKays 1841 Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, we have chosen a potpourri of fifty varyingly disreputable episodes that cover around five thousand years of human experience and billions of years of life itself. Since we have tried to keep each entry short, we have provided a few suggestions for further reading at the end of the book; a bit of browsing around on the Webwhile remembering that what you find there is mostly without guarantee of factual accuracywill yield a trove of other information.

Some of the events portrayed in this book are familiar, others obscure. Some involve intentional misrepresentations, while others more closely reflect misguided general preconceptions. Some reveal the depths to which human callousness and meanness of spirit can descend, whileto take a generous viewothers actually added to the sum total of human contentment. But, considered together, they hint at two contradictory aspects of the human experience.

One of these is the constancy and durability of basic human nature: our species as a whole has evidently changed not one whit since human beings first began to write down their thoughts and feelings and experiences. The other, in contrast, is how dramatically the sands of history may shift: how our preoccupations and beliefsand what, as a society, we have been prepared to be deceived aboutchange with the passage of time.

As authors, we have refrainedwisely, we hopefrom attempting to fit any of these fifty episodes into a wider view of history, or of how it unfolds. Human experience is, after all, far too haphazard for that. But we do think that each of them will make its own point. And since it turns out that not all cons are altogether reprehensibleindeed, some fraudsters were actually perfectly genialwe have buried a tiny fraud of our own somewhere in this book. See if you can spot it.