For my mother and my father

And for my son, Shibli

Ababooboo

CONTENTS

Guide

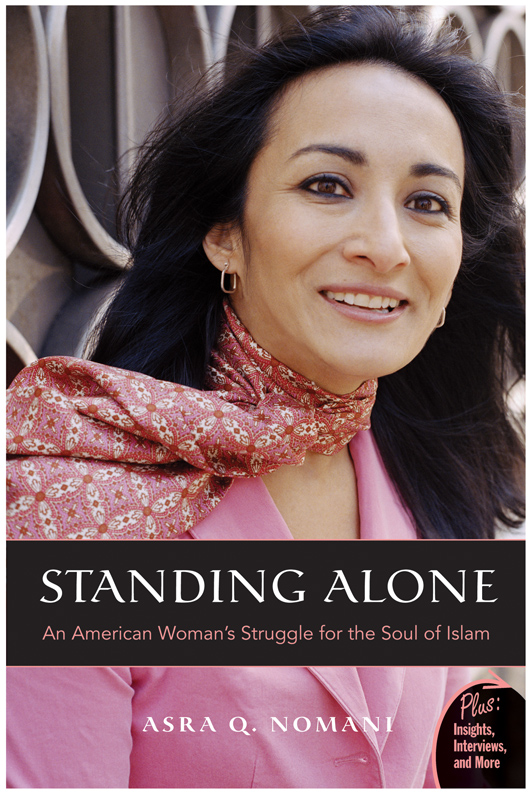

This is a tale of a journey into the sacred roots of Islam to try to discover the role of a Muslim woman in the modern global community. This book is a manifesto of the rights of women based on the true faith of Islam. It heralds a revolution in the Muslim world of the twenty-first century.

My book is about sorting out the contradictions about religion. Two defining moments shaped my relationship with my religion: the murder of my friend Daniel Pearl and the birth of my son, Shibli Daneel Nomani. The men who plotted the kidnapping of my friend did the five daily prayers that are one of the five pillars of my religion; and the men who killed my friend did so in the name of my religion. The man who is the father of my baby went to the mosque for his Friday prayers but did not stand beside me when I brought my baby into the world. He considered me illegitimate in the eyes of my religion because, while foolishly in love, we werent married when we conceived our baby. Others called me a criminal in the name of Islam.

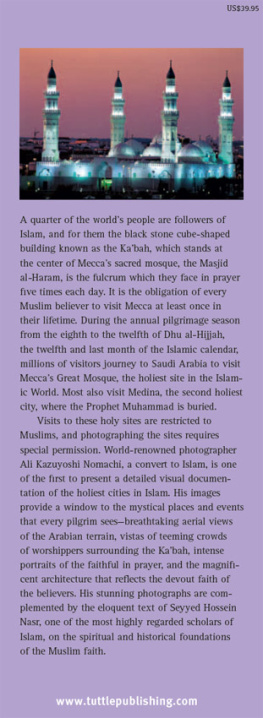

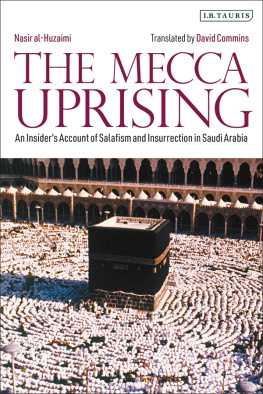

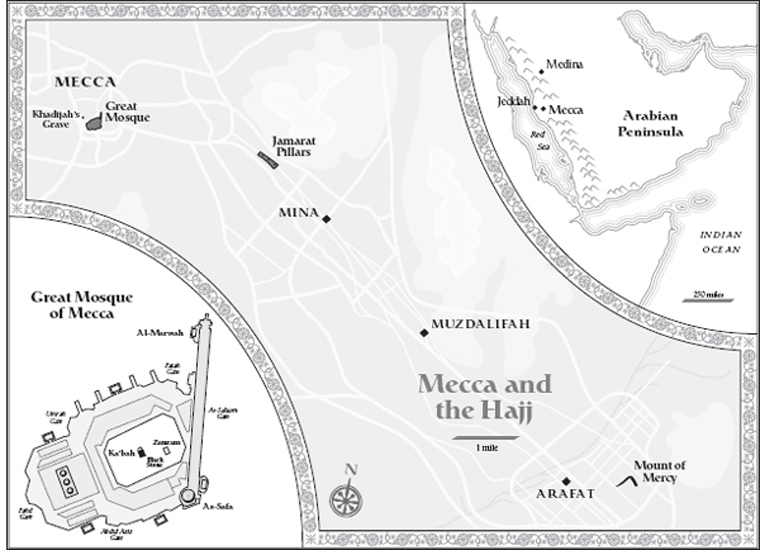

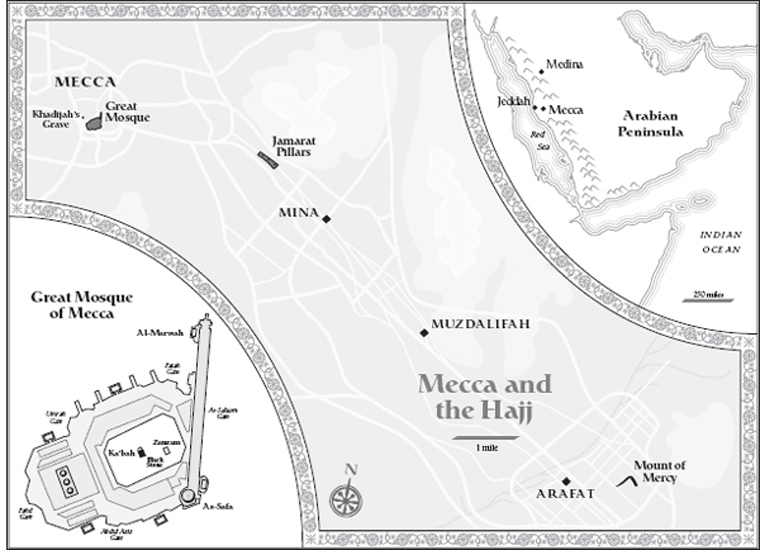

I was very much at odds with my religion. But instead of turning away from Islam, I decided to find out more about my faith. From my home in Morgantown, West Virginia, I embarked on the holy pilgrimage to Mecca, the birthplace of Islam, in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, one of the most repressive regimes in the world for women. What happened there shocked me. The hajj became the catalyst to my empowerment as a woman in Islam.

The hajj allowed me to walk a living history that pulses with meaning to Muslims. It is best described as a journey that follows the path of Adam, the first prophet in Islam; Abraham, the father of Islam; and Muhammad, the prophet of Islam and the last messenger of God, and a man so revered by Muslims the words peace and blessings be upon him follow his name. But I walked with a different mindfulness, following the struggles, strengths, and triumphs of the women of my religion. I traced the path of the great women in Islam starting with Eve, who, contrary to biblical opinion, was not responsible for original sin; Hajar (or Hagar), the single mother of Islam; and Khadijah, the first wife and patroness of the messenger of Islam. As my guides, I had with me living models for the best in Islam, my mother and my father. And as my beacons for the future of Islam, I had my young niece, nephew, and son.

The journey took us to the three holiest mosques in the Muslim world in the cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem. I crossed thresholds into the space where the Muslim civilization was born. I felt beneath my feet the earth where the first Muslims risked death to practice their religion. And I gazed up at the sky that served as the canopy for the forgotten mother of Islam, Hajar.

On my journey, a remarkable transformation happened in my understanding of my religion. I uncovered the hidden secrets of the strength of Muslim women in the earliest years of Islamic history. I discovered the legacy of Muslim women who marched into battle with spears, challenged the prophet, and sculpted the society that was the first Muslim society. They prayed, worked, and pioneered a new community with men, empowered by their leader, the prophet Muhammad, to contribute fully and express themselves completely. The prophet was indeed the Muslim worlds first feminist.

I returned to my home in Morgantown with an awakened understanding of the highest ideals of Islam for both women and men and for the community. The hajj gave me the courage to act on the ultimate conviction that women can be fully engaged members of the Muslim community. What I discovered was sad testimony to the ways in which the original might of women in Islamic history have been erased by religious clerics and men who are more interested in power and control than the ideals originally set out by Muslim society. It led me into a deep confrontation with tradition, power, and fear.

What I realized is that the core values of all religions and cultures are the ones that serve us best: truth, knowledge, love, and courage. Living with truth allowed me to free myself from the duplicities, contradictions, and shame that so often constrain us. Knowledge about the heart of my religion helped to liberate me as a woman in Islam. Scholars of yesterday and today freed me from oppressive traditions that I was expected to inherit. Through their practice of ijtihad, or critical reasoning, and their individual strength in standing up to forces of darkness, they blew open the doors of my religion to me. I am grateful to them for their scholarship. The love of my parents, my friends, and my spiritual community encouraged me to explore territories that I had never charted. My mother and my father gave me the freedom to think, explore, and learn. They allowed me to find my voice, the result of which is this book. And they embraced me always with unconditional love.

The final theme of this book is couragethe courage to be honest and stand up for justice. It is a theme that is as universal today as it was yesterday and will be tomorrow. I hope to encourage others to live with honesty and to live peacefully with their religion through their own personal searches and faith in the belief that the divine force of the universe is compassionate, loving, kind, and accepting. This is a book about a Muslim woman in America. But this is also a book for women and men of all faiths.

ALLAHABAD, INDIAOne hot winter afternoon, I was lost in India on the banks of the Ganges, a river holy to Hindus. I was meandering with an American Jewish friend on a road called Shankacharaya Marg. By chance, my path intersected with the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhists, the Dalai Lama, inside an ashram, and he set me off on my holy pilgrimage to the heart of Islam.

It was January 2001, and I was, quite fittingly, in the city of Allahabad, the city of Allah, the name by which my Muslim identity taught me to beckon God. In Islam, Allah is our Arabic word for God. Born about a thousand miles westward along the Indian coastline in Bombay, India, I had evoked God with this name from my earliest days.

Although a Buddhist, the Dalai Lama, like millions of Hindu pilgrims, was in a dusty tent village erected outside Allahabad to make a holy pilgrimage to the waters there for the Maha Kumbha Mela, an auspicious Hindu festival. He joined the chanting of a circle of devotees dressed all in white. When they had finished, I followed the Dalai Lama to a press conference in a building surrounded by Indian commandos and his own bodyguards. Religious fundamentalism and fanaticism are wreaking havoc throughout the world, and in India they are redefining Hindu and Muslim communities that used to coexist peacefully. The demolition of a sixteenth-century mosque called Babri Masjid sparked one of Indias worst outbreaks of nationwide religious rioting between Hindus and the Muslim minority; two thousand people, mostly Muslims, were killed. The cycle of hatred continued until that day when the general secretary of the sectarian World Hindu Council, Ashok Singhal, called Islam an aggressive religion. At the press conference an Indian journalist raised his hand. Are Muslims violent? he asked.