Presocratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction

Catherine Osborne

PRESOCRATIC PHILOSOPHY

A Very Short Introduction

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi So Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Published in the United States

by Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Catherine Osborne, 2004

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Database right Oxford University Press (maker)

First published as a Very Short Introduction 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 13: 9780192840943

ISBN 10: 0192840940

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by RefineCatch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

Printed in Great Britain by

TJ International Ltd., Padstow, Cornwall

Contents

List of illustrations

Mummy case portrait mask of a young woman, from Roman Egypt (1st to 2nd century AD)

Christies/Werner Forman Archive

Papyrus scraps from Strasbourg

LInstitut de Papyrologie de Strasbourg/Bibliothque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg

Ensemble a from the reconstruction of the Strasbourg Papyrus

Bibliothque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg

Ensemble d from the reconstruction of the Strasbourg Papyrus

Bibliothque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg

Temple of Hera at Agrigento

TopFoto.co.uk

Mount Etna

TopFoto.co.uk

The alternation of love and strife

Minotaur depicted on the black-figure interior of an Attic bilingual cup (c.515 BC)

Christies/Werner Forman Archive

Vase depicting Sarpedon (early 5th century BC)

The Louvre. Photo RMN/Herv Lewandowski

Miletus

Alan Greaves, University of Liverpool

Detail of The School of Athens (150911) by Raphael

Vatican Museums. Alinari Archives/Corbis

Crossroads

Images.com/Corbis

How can Achilles catch the tortoise?

How can the runner move from A to B?

Bendis on an Attic red-figure cup (430420 BC)

Antikensammlung des Archologisches Instituts, Tbingen

A warrior and his two black squires, Athenian black-figure vase, painted by Exekias

British Museum

Statuette of Taweret, Egyptian goddess of fertility (c.664610 BC)

Egyptian Museum, Cairo/Werner Forman Archive

Democritus by Antoine Coypel (16611722)

The Louvre. Photo RMN/Herv Lewandowski

Electron microscope image of the fossilized shell of a tiny ocean animal

Dee Breger

Jacobs Ladder (c.1800) by William Blake

British Museum/Bridgeman Art Library

The River Caster at Ephesus

From Dietram Muller, Topographischer Bildkommentar zu den Historien Herodotos

Symposiasts with lyres, scene on Attic red-figure rhyton

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. The Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund. Photo: Katherine Wetzel

Vase depicting animal sacrifice

The Louvre. Photo RMN/Chuzeville

Diagram of Pythagorass theorem

Political rhetoric or democracy

Jean Michel [www.isle-sur-sorgue-antiques.com]

Death of Socrates (1780) by Watteau

Muse des Beaux-Arts, Lille. Photo RMN/P. Bernard

Athletes exercising, on Attic red-figure kylix, attributed to the Carpenter Painter (c.515510 BC)

J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

The Rape of Helen (date unknown) by Johann Georg Platzer

Wallace Collection/Bridgeman Art Library

The publisher and the author apologize for any errors or omissions in the above list. If contacted they will be pleased to rectify these at the earliest opportunity.

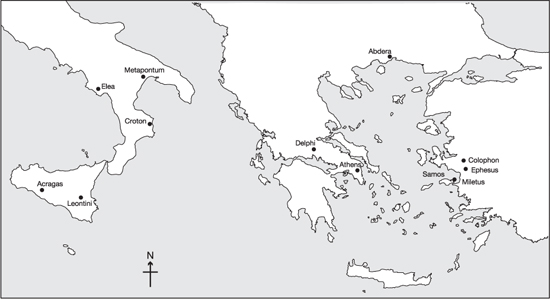

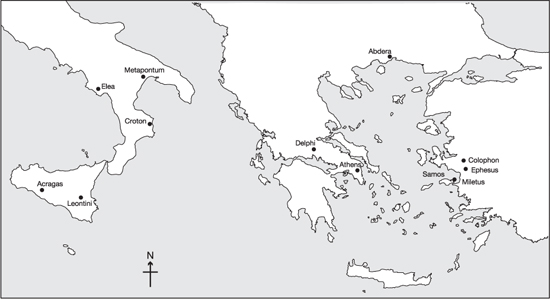

Home cities of chief Presocratic Philosophers

Time line A Presocratic Philosophers and Plato and Aristotle, showing approximate dates of writing and/or teaching

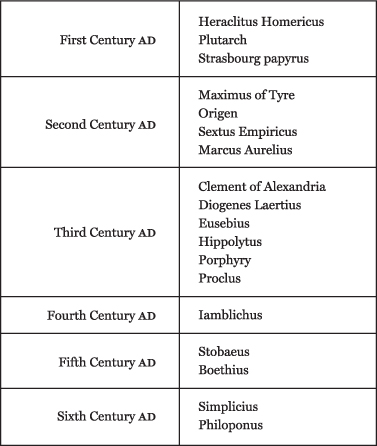

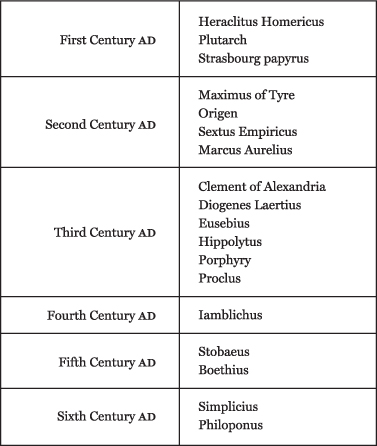

Time line B Writers of the first six centuries AD who quote from the Presocratic Philosophers

A note on the pronunciation

This book is full of men whose names end in...es. The e in this last syllable is always pronounced (it is not a silent e) and it is always long, so that the last syllable of these names rhymes with please. This may be familiar to you from the name Socrates. In all our examples, Thales, Anaximenes, Empedocles, Parmenides, the ending is pronounced in this way.

It is traditional to anglicise the pronunciation of Greek names in accordance with long-established custom, by making the vowels that are long in Greek long in English: thus Thales has a long a (as in came) and Pythagoras has a long y (as in fly), Zeno has a long e as in theme and a long o as in tome, Heraclitus has a long i as in pie. Most of the other vowels are short.

There are a few exceptions to the long-vowel-rule: the first e in Heraclitus should be long: some people do say hear-a-cli-tus but most people pronounce it short; and the first o in Socrates should be long but it is standardly shortened in English.

The following chart shows where the stress is placed in English pronunciation of the main names (stress the accented vowel):

Thles

Empdocles

Xenphanes

Protgoras

Parmnides

Cllicles

Melssus

Anaxmenes

Demcritus

Heracltus

Scrates

ntiphon

Anaximnder

Anaxgoras

Pythgoras

Grgias

Zno

Introduction

Before computers were invented people published their thoughts as printed marks in books. Before printing was invented their written thoughts were laboriously copied by hand into codices. Before codices were invented they made their marks on rolls of papyrus or engraved them on stone, on wax blocks, or in the sand. Before writing was invented they sang songs and entertained each other with the telling of tales, tales of how the heroes fought at Troy, how the giants fought the gods, how the earth brought forth living things, and where the dead go when they are no longer seen.

Next page