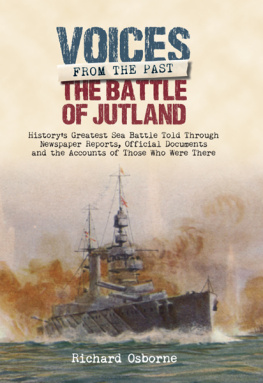

THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND

Historys Greatest Sea Battle Told Through Newspaper Reports, Official Documents and the Accounts of Those Who Were There

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Richard Osborne

The right of Richard Osborne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-453-4

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-456-5

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-455-8

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-454-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com,

email

or write to us at the above address.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 10.5/12.5 Palatino

Contents

Foreword

F or most British people brought up believing in the invincibility of the Royal Navy, Jutland, which was the largest naval action and the only full-scale clash of battleships in the First World War, was probably the most disappointing battle fought during the Great War. The battle took place at a time when the British Grand Fleet had been awaiting an opportunity to face the German High Seas Fleet for almost two years since the outbreak of the war. Furthermore, the Royal Navy and the British public expected that the High Seas Fleet would suffer very severe losses as a result of any fleet encounter. Unfortunately, by 1916, to the British public the Royal Navy seemed to be scarcely involved in the war, especially when compared with to the casualties suffered by the Army. Consequently, the failure to destroy the German fleet at Jutland had an adverse effect on public opinion, and confidence in the Royal Navy suffered accordingly.

The heaviest British losses occurred during the first phase of Jutland when a force of six battlecruisers and four modern fast battleships commanded by Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty, lost two battlecruisers and two destroyers while engaging a German squadron of five battlecruisers which lost just two destroyers. Once the main action was joined, the ratio of capital ships was seven to five in favour of the Royal Navy. The latter lost one battlecruiser, three old armoured cruisers and six destroyers while the Germans lost one battlecruiser, one predreadnought battleship, four cruisers and three destroyers. Furthermore, the High Seas Fleet suffered far more damage than it inflicted, in terms hits on surviving ships, and once Scheer encountered the full might of the Grand Fleet he had only one aim, namely to avoid further combat and get back to base under the cover of darkness.

While the Germans could claim a tactical victory in the initial battlecruiser duel, it is also clear that they were defeated once the Jellicoes battleships joined the fray. Furthermore, despite sinking more British ships and causing more fatalities, the Germans suffered a strategic defeat from which they never recovered. In one respect Jutland assisted the Royal Navy by shattering the over-confidence in materiel while at the same time revealing deficiencies in leadership and training. A second Trafalgar on 31 May 1916, would have, in all probability, restored British naval supremacy for decades but, the failure to annihilate the High Seas Fleet meant that the Royal Navy began to lose its prestige both at home and abroad and has been in decline ever since.

The aim of this book is to record and evaluate what people thought during and after the Battle of Jutland using official records, newspaper reports and personal accounts. However, it was never my intention to repeat the detailed personal accounts of the battle found in the earlier works by Fawcett and Hooper excellent analysis of the actual fighting.

This brings us to the vexed question of the quality and reliability of the official sources available at the National Archives and elsewhere. Like most others writing about Jutland I have chosen to use despatches as my primary source because it was the first to be published and appears to offer a basic and objective evidence of the course of the battle. This source contains original despatches, track charts, a list of signals and other raw data from which it is difficult to provide an understandable account. In February 1919, the then First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, allocated that task to a committee led by the Director of Navigation, Captain John Harper, but publication of the so-called Harper Record was abandoned when Beatty became First Sea Lord. Instead, the latter arranged for the despatches to be published in 1920 but once it became known that Beatty had ordered Captain Harper to make alterations, opponents of the new First Sea Lord became alarmed that he might to be writing his own biased account under the guise of it being the considered verdict of the Admiralty. Subsequently, Harper discussed Beattys corruption of the first proposed account of the Harper Record in his The Truth About Jutland, which was published Despite evidence of Beattys interference, the despatches are generally assumed to be accurate and impartial even though all despatches from ships of the Battlecruiser Fleet were sent to Beatty prior to being forwarded to London. No doubt much original material was destroyed decades ago and it is now no longer clear to what extent the original despatches are an accurate reflection of what took place. There can be little doubt that Beatty interfered with every one of the official publications but to what extent remains unclear. Beattys actions post-Jutland appeared to be aimed at achieving a favourable public image of the Battle Cruiser Fleets role and his leadership of this force. In effect he seems to been trying to show that his operational ideas had been more successful than they actually were, thereby making them appear preferable to Jellicoes cautious approach.

Another weakness of the despatches concerns the variable quality of the reports from Flag and Commanding Officers. Those used to reading Reports of Proceedings from the Second World War, will be disappointed by the lack of accuracy and detail. At the time of Jutland commanding officers were only required to submit a report and there was no obligation or expectation to use as much evidence as possible or make it as accurate as possible by confirming times, reporting fire-control data and information from other ships.

Because of the absence of a Naval Staff, Jellicoe was able to set up self-seeking and self-serving Grand Fleet Committees to learn from the experience of Jutland. The work done by these committees was instrumental in improving the battle-worthiness of the Royal Navy such that by 1918 the latter would have crushed the High Seas Fleet had it encountered the Grand Fleet. However, for all their good work, these committees chose to ignore the dangerous magazine practices that had been allowed to develop in the years leading up to Jutland, preferring to blame a lack of armour for the loss of the battlecruisers. Researchers hoping to find documentary evidence of the lax attitude to cordite and its explosive consequences will be disappointed because, sadly, most of it seems to have been weeded out many years ago. All that remains are a few fragments from larger reports.

Next page