About the Author

Brian A. Pavlac is the Herve A. LeBlanc Distinguished Service Professor and chair of the Department of History at Kings College in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. He is the author of Witch Hunts in the Western World: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials and articles on Nicholas of Cusa and excommunication as well as the translator of Balderichs Warrior Bishop of the Twelfth Century: The Deeds of Albero of Trier.

Acknowledgments

I was interested in history from a young age, as most kids are. Too often, as they grow older, kids lose their fascination with the past, partly because it becomes one more thing they have to learn rather than a path of self-understanding or even just neat stuff. Wonderful teachers taught me history through the years, and partly inspired by them, I foolishly went on to study history in college. Before I knew it, history became my intended profession. Since then I have been fortunate to make a living from history.

In teaching courses over the years, I found my own voice about what mattered. Instead of simply sharing my thoughts in lectures, I produced this book. Former teachers, books I have read and documentaries I have viewed, historical sites I have visited, all have contributed to the knowledge poured into these pages. Likewise, many students, too many to be named, have sharpened both words and focus. I owe thanks to the many readers whose suggestions have improved the text. For their help to me in getting this project as far as it has come, I have to thank a number of specific people. I appreciate my editor, Susan McEachern, who gave the book her time and consideration and offered a second edition, and her associate, Carrie Broadwell-Tkach, as well as Michele Tomiak, Audra Figgins, and Jehanne Schweitzer. Various people have read drafts and offered useful suggestions: Mark Reinbrecht, Linae Steitz Marek, Megan Lloyd, Gabe Gross, and especially Jean OBrien. I thank my departmental colleagues Charles Ingram, Nicole Mares, Cristofer Scarboro, Daniel Clasby, and Ada Borkowski-Gunn for their feedback from teaching. The comments by anonymous readers for the publisher have been much appreciated. Helping me with reviewing and editing have been my daughters, Helen K. Pavlac and Margaret Mackenzie Pavlac. Finally, most of all, my spouse, Elizabeth Lott, has sustained me through it all. Her skills in grammar, logic, and good sense have made this a far better book.

The final version is never final. Every new history source I read makes me want to adjust an adjective, nudge a nuance, or fix a fact. With every reading of this text, I find room for improvement. I have made a great effort for accuracy. Should any errors have crept in, please forgive the oversight and contact me with your proposed corrections.

Brief Contents

CHAPTER

Historys Story

N ow can never take place again. Each moment is surrendered to the past, forgotten or remembered. In our personal lives, we treasure or bury memories on our own. Our larger society, however, entrusts historians with preserving and making sense of our collective existence. Historians recapture the past by applying particular methods and skills that have been nurtured over the past few centuries. Although such processes are not without challenges, the work done by historians has created the subject known as Western civilization.

THERES METHOD

How do we know anything? is our starting point. As humans, some of our knowledge comes from instinct: we are born with it, beginning with our first cry and suckle. Yet instinct makes up a tiny portion of human knowledge. Most everything we need to know we learn in one way or another. First, we learn through direct experience of the senses. These lessons of life can sometimes be painful (fire), other times pleasurable (chocolate). Second, other people teach us many important matters through example and setting rules. Reading this book because of a professors requirement may be one such demand. Third, human beings can apply reason to figure stuff out. This ability enables people to take what they know, then learn and rearrange it into some new understanding.

The discipline of history is one such form of reasoning. History is not just knowing somethingnames, dates, factsabout the past. The word history comes from the Greek word o for inquiring, or asking questions. The questioning of the past has been an important tool for gaining information about ourselves. Indirectly, it helps us to better define the present.

Quite often authorities, namely the people in charge, have used history to bind together groups with shared identities. For many peoples, history has embodied a mythology that reflected their relationship to the gods. Or history chronicled the deeds of kings, justifying royal rulership. History also sanctioned domination and conquest of one people over another. Most people are raised to believe that their own country or nation is more virtuous and righteous than those others beyond their borders. The history of Western civilization abounds with examples of these attitudes.

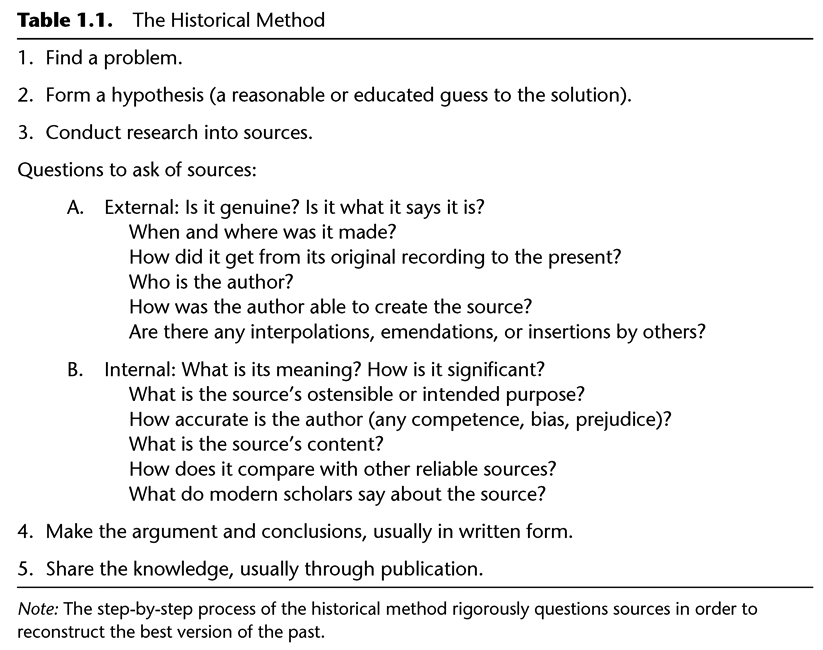

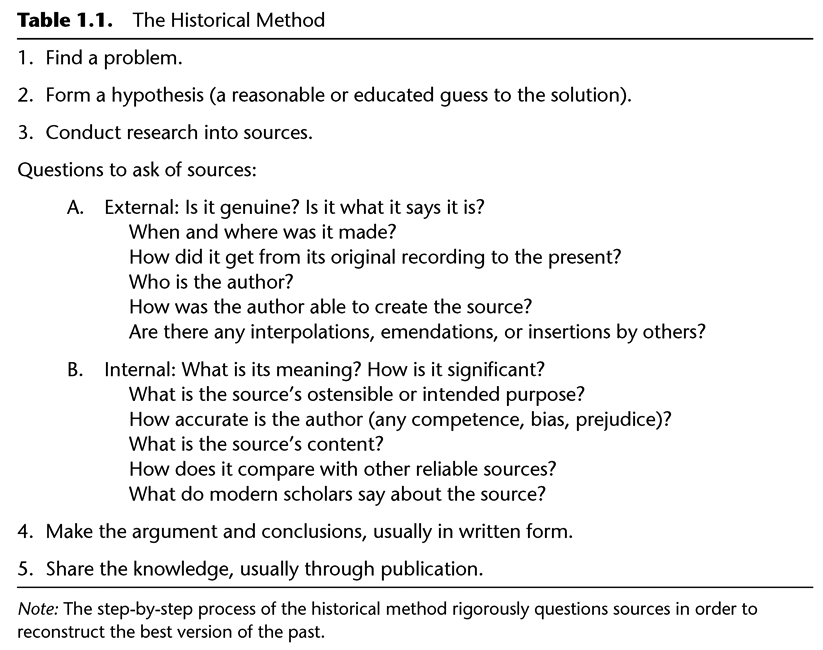

Then, about two hundred years ago, several men began to try to improve our understanding of the past. These historians began to organize as a profession based in the academic setting of universities. They imitated and adapted the scientific method (see chapter 10) for their own use, renaming it the historical method (see table 1.1). In the scientific method, scientists pose hypotheses as reasonable guesses about explanations for how nature works. They then observe and experiment to prove or disprove their hypotheses. In the historical method, historians propose hypotheses to describe and explain how history changes. The two main problems historians have focused on are causation (how something happened) and significance (what impact something had). History without explanations about how events came about or why they matter is merely trivia.

Unlike scientists, historians cannot conduct experiments or run historical events with different variables. Historians cannot even obtain direct observational evidencethere are no time machines. Instead, historians have to pick through whatever evidence has survived. They call these data sources. At first, historians sought out sources among the written records that had been preserved over centuries in musty books and manuscripts. Eventually historians learned to study objects, ranging from needles to skyscrapers, made by people. Obviously, not all sources are of equal value.

Those sources connected directly with past events are called primary sources. These are most important for historical investigation. When evaluating these primary sources, historians face two predicaments. For one, evidence for many events has not survived at all or remains only in fragments. For another, some people have forged sources. Much of historical research involves questioning human character, deciding who is honest or deceitful, trustworthy or undependable. Then, through careful examination and questioning, historians try to write the most reliable and accurate explanation of past events, carefully citing their sources.

As the last and most important part of the historical method, professional historians have shared their information with one another. They produce secondary sources, usually books and articles. At academic conferences and in more books and articles, historians learn from and judge one anothers work. They debate and challenge one anothers arguments and conclusions. Often a consensus about the past emerges. Generally, agreed-on views begin to appear in