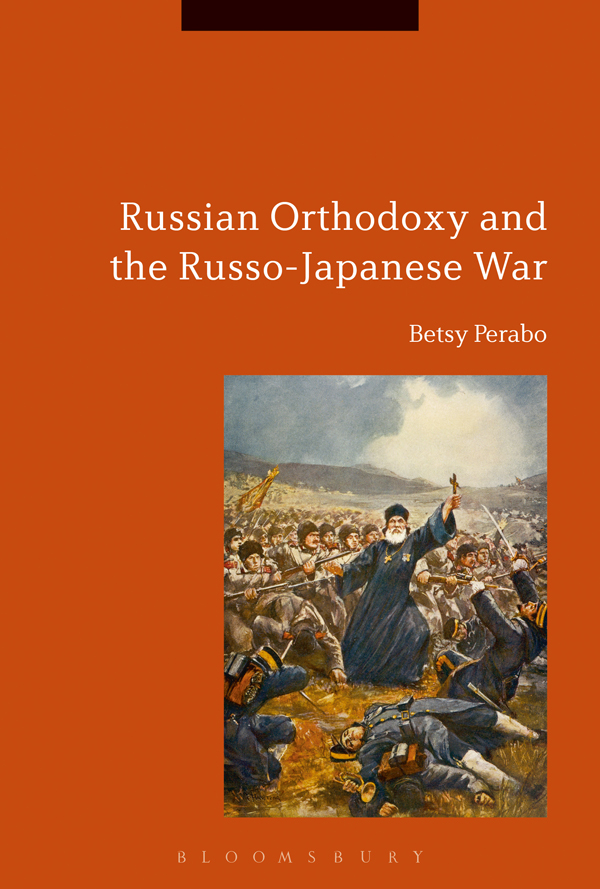

Russian Orthodoxy and the Russo-Japanese War

Russian Orthodoxy and the Russo-Japanese War

Betsy C. Perabo

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

In my Fall 2008 course on Religion and War at Western Illinois University, my students and I read and discussed Brian Daizen Victorias Zen at War (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006). His brief treatment of the Russo-Japanese War provided the inspiration for this book. I am thankful to the students in that course, as well as to those in several iterations since, for serving as critics of and contributors to my developing theories about the relationship between religion and war.

Many scholars in the fields of Christian ethics and Russian and Orthodox studies have assisted me throughout the course of this project, and I am grateful to each one of them. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to present work at conferences of the American Academy of Religion, the Society of Christian Ethics, the Association for the Study of Eastern Christian History and Culture, and the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies; the feedback from participants has been very helpful. The 2014 National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar on The Late Ottoman and Late Russian Empires: Citizenship, Belonging, and Difference, directed by Dina Khoury and Sergei Glebov, provided me with time to research at the Library of Congress as well as an enthusiastic cohort of colleagues in both Russian and Ottoman studies.

The Summer Research Lab at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign provided an excellent environment for my work in the summers of 2010 and 2015, and I am thankful to its organizers and participants, as well as to the library staff at the Slavic Reference Service. Librarians Joe Lenkhart and Jan Adamczyk were especially helpful during my time there. I am grateful to them and all of their excellent colleagues in the International and Area Studies Library.

In addition, I am extremely grateful to Greg Baldi, Jesse Murray, and Fr. John Bartholomew for their extensive comments on portions of the book. Fr. Bartholomew also generously shared the fruits of his many years of research on Nikolai of Japan. At various points in the process of conceptualizing, researching, writing, and editing the book, I received valuable help and guidance from Doreen Bartholomew, Krista Bowers Sharpe, Jesse Couenhoven, Margaret Farley, Barb Harroun, Scott Kenworthy, Erich Lippman, Predrag Matejic, Febe Pamonag, Aristotle Papanikolaou, Ida Perabo, Susan Perabo, Lee Ann Pingel, Howard Rhodes, Christopher Stroop, and Mark Totten, as well as my editor at Bloomsbury, Emma Goode, and anonymous reviewers.

Portions of this book were completed during a sabbatical year from Western Illinois University. I am grateful to the university for providing this support, and also to my colleagues in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies for their comments on the project over the years. I also thank my friends and family, especially my parents, Fred and Ida Perabo, and Susan Perabo, Shaan Chilson, Brady, and Chase. Their support has been invaluable.

Citizens of Paradise

In October 1904, a memorial service was held in Tokyo to honor Japan But this October service was unique: its leader was a native of Russia, an Orthodox Christian bishop who had lived most of his life in Japan. When the war broke out in early 1904, the bishop, Nikolai, had said that he would stop leading the public prayers of the Japanese Orthodox Church so as to avoid praying for the success of the Japanese emperor and military in their fight against his own nation and thus being seen as a traitor or a hypocrite. But when he discovered the service was being planned, he recorded in his diary that he considered it necessary to participate. He wrote,

A week ago the Japanese [Orthodox] announced a memorial service (panikhida) for those killed in the war, and today performed it after the liturgy. I considered it necessary to participate in it. Robed in a mantle, and having gone up onto the ambo

Nikolai does not include the full text of the service in his diary, but it would likely have contained the plea: Restore to me the homeland of my hearts desire, making me once more a citizen of Paradise.the heavenly kingdom is granted to these soldiers after they have provided good service to their own earthly kingdom. That this service involves fighting against his own beloved countrywhose losses pain him and whose rare victories give him joyappears to be irrelevant.

Christians and the Language of War

Nikolais reflections on a short war fought more than a century ago may seem to have little relevance for the modern day. They are difficult to translate into the language of the just war tradition, which Western Christians, especially English-speaking Protestants and Roman Catholics, almost invariably use as the framework for moral conversations about war.

However, the writings of Nikolai of Japan and other Christian responses to and characterizations of the Russo-Japanese War discussed in this book highlight the limitations of the just war tradition in encompassing Christian conversations about war. These sources point toward connections between holiness and war that are different from those found in the Western just war tradition and that are in certain respects deeper.

Do the Russian Orthodox writings fit instead into what might be called a holy war tradition, then? Not exactly; but analysis of that tradition can provide a useful basis for analysis of the Russo-Japanese War. Holy wars may be defined as conflicts that have a strong ideological, motivational, social, or other connection with one major religious tradition or another, according to James

These criteria indicate that there is some similarity between the just war and holy war models in the West; indeed, John This is to be expected given Christian understandings of the relation between justice and holiness. In holy war traditions, sovereigns are to be obeyed because they are put in place by God, but they are also usually depicted as noble and just. The cause of protecting Christians or expanding Christendoms reach is fulfilling Christs command to make disciples of all of the nations while also creating a better world by improving the lives of those who are or will become Christian. Soldiers who go into battle convinced of the importance of laying down ones life for ones friend (John 15:13) may be soliciting Gods favor or securing their place in heaven, but they are also virtuous in that they are expressing their love of Christ and their fellow soldiers and citizens.

Though the holy war idea described by Johnson helps expand the moral language of war beyond the parameters of the just war tradition, the categories of just war and holy war do not fully encompass Christian conversations about war. Christianity is useful not only as a means of assessing whether it is rightwith regard to justice or holinessto go to war, or of prescribing how soldiers should behave during wartime; it also serves as both a lens through which war is viewed and an overarching interpretive framework, providing an architecture for rituals intended to give comfort or motivate action and presenting a vision of death and the afterlife that may reassure or inspire soldiers and those who love them.

As the historical material in this book will demonstrate, participants in the Russo-Japanese War seldom thought about the major just war or holy war categories described here in isolation from the rest of their religious lives and activities. In conducting the memorial service described earlier, Nikolai of Japan was not making a case for either just war or holy war; he was living out his understanding of the Christian faith. The same was true for many other Russian Orthodox political, military, and religious leaders, as well as ordinary soldiers and citizens.