Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

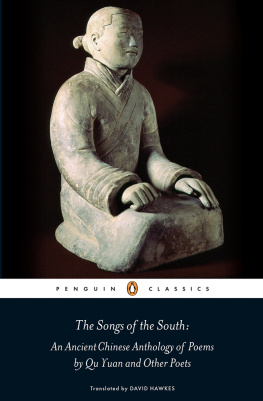

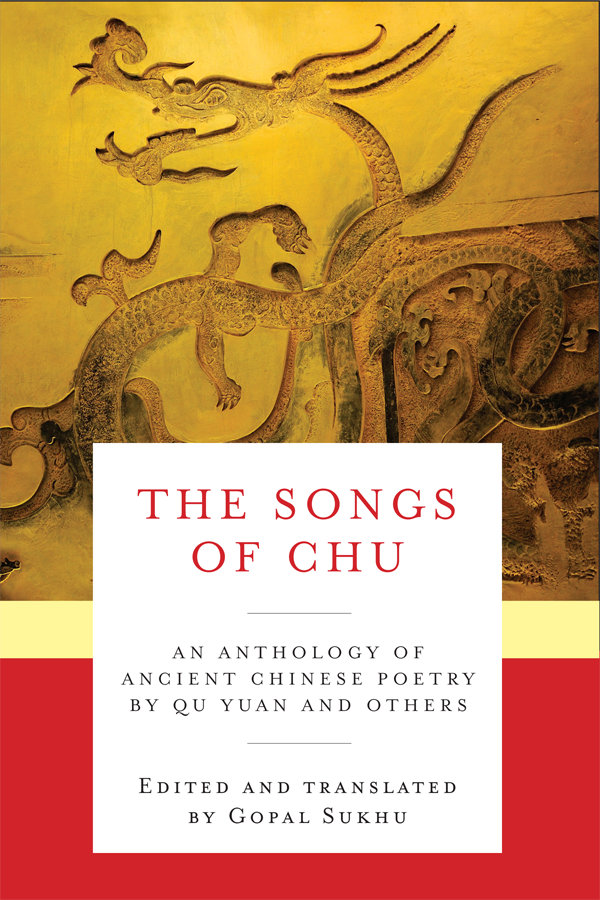

THE SONGS OF CHU

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

EDITORIAL BOARD

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

Burton Watson

Wei Shang

The Songs of Chu

An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poetry by Qu Yuan and Others

Edited and translated by Gopal Sukhu

Columbia University PressNew York

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support to this book provided by Publisher's Circle members John J. S. Balcom and Yingtsih Balcom.

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange and Council for Cultural Affairs in the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press wishes to express its appreciation for assistance given by the Pushkin Fund in the publication of this book.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54465-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Qu, Yuan, approximately 343 B.C.-approximately 277 B.C. | Sukhu, Gopal, editor, translator.

Title: The songs of Chu : an ancient anthology of works by Qu Yuan and others / edited and translated by Gopal Sukhu. Other titles: Chu ci. English

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, 2017. | Series: Translations from the asian classics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016045048 (print) | LCCN 2017004499 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231166065 (cloth : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780231166072 (pbk.)

Classification: LCC PL2661 .C4613 2017 (print) | LCC PL2661 (ebook) | DDC 895.1/11dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016045048

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Noah Arlow

To the memory of

Seth Bernard Adams

Merchant Mariner

and jazz aficionado

who gave me my first books on Asia

Contents

Special thanks to the two anonymous readers for Columbia University Press; its freelance copyeditor Mike Ashby and in-house editor Leslie Kriesel; as well as Mick Stern, Cary Plotkin, John Major, Kim Dramer, Mary Beth Maher, Ammiel Alcalay, Constance A. Cook, Galal Walker, and Li Minru for their valuable comments on the manuscript. I hereby express my appreciation to the Schoff Fund at the University Seminars at Columbia University for their help in publication. Material in this work was presented to the University Seminar on Early China. Thanks to Li Feng, Guo Jue, and the other members of the Early China Seminar at Columbia University for their critiques, encouragement, and support. I am indebted to Robert Hymes, Haruo Shirane, and Shang Wei for giving me the opportunity to test my ideas on Columbia University graduate students; and to Ari Borrell for providing me with unexpected research tools. My heartfelt gratitude also to my wife, Hanna Kim; my daughter, Uma; and my sisters, Radha and Kushelia Sukhu, for helping me stay on course, and to Mr. and Mrs. S. Y. Kim for kindly providing me a peaceful and beautiful place to work.

The first man ever to be known for his poetry in China was Qu Yuan (340?278? B.C.E. ). His work is the core of the Chuci , or Songs of Chu , the second-oldest anthology of Chinese verse. He was a high minister in the southern state of Chu, serving both King Huai (r. 328299 B.C.E. ) and his successor, King Qing Xiang (r. 298263 B.C.E. ). So distinctive and influential is his work, which includes some of the most beautiful liturgical poetry in the world, that literary historians think of it as the second beginning of Chinese poetry, the first being the ancient and quasi-scriptural Shijing , or Book of Songs . Yet the Dragon Boat Festival, held in his honor every year, is less a celebration of his poetry than a commemoration of his suicide.

What drove him to suicide was frustration and despair that began when his feckless king believed the slander of his enemies and demoted him. The king later died a hostage in another state, having been misled by royal officers, among them his own son. The same son, when his brother succeeded his father as king, made sure that Qu Yuan was sent into exile, where in protest and grief he drowned himself. The poem that won him the most fame, Li sao , or Leaving My Sorrow (also known as Encountering Sorrow), was supposedly written shortly after his demotion. Yet there is much in the poem that was obscure even to those reading it only a century later. Part of the reason for this is that it makes reference to some of the more esoteric aspects of the culture of Chu.

According to the ancient Chinese historical records, the ancestor of the Chu royal family, Yu Xiong , was originally a minister of the Shang dynasty (16001046 B.C.E. ) who, horrified by the excesses of its last king, fled to the state of Zhou and served King Wen as general. King Wen, with his help, overthrew the evil Shang king and established the Zhou dynasty (1046256 B.C.E. ). King Wens successor, King Cheng, rewarded Xiong Yi , the descendant of the defector Yu Xiong, with the title of viscount and a parcel of land in the southa barbarian region, in the eyes of the north, known as Chu . It was wild and uncultivated, requiring a great deal of work, often with the forced labor of local tribes, to make it habitable. Eventually Xiong Yi built his capital at Danyang in Hubei. The viscounty gradually expanded, and, by the reign of Xiong Qu , in the mid-ninth century, it was strong enough to declare its independence from the Zhou dynasty, which had for a long time treated it as mere wilderness to be raided periodically for metal ore and slaves. Xiong Qu made it a kingdom, but not for long; pressure from King Li (877841 B.C.E. ) of the Zhou brought Xiong Qu back into the fold.

Around the year 771 B.C.E. , a combination of internal conflict and barbarian invasion from the north resulted in the flight of the Zhou royal family to the eastern city of Luoyang, the reduction of the kings status to mere figurehead, and the eventual disintegration of the dynasty into powerful independent and contentious states. Thus began what is known as the Spring and Autumn period (772476 B.C.E. ), during which Chu grew both in power and territory, expanded east and north into the Yellow River region, and vied with the larger states. By the Warring States period (475221 B.C.E. ) it was the largest, both in terms of land and population, of the six main states contending for supremacy.

As it rose, Chu not only increased its wealth by absorbing both southern and eastern regions but also created an eclectic culture whose glories rivaled anything in the north. The extent to which that was true was gradually forgotten when Chu fell to Qin, its main rival, in 223 B.C.E . After that, the old clichs about its barbarism gradually replaced the memories of its historical realities.