Princeton Architectural Press

A McEvoy Group company

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

www.papress.com

Published by arrangement with Redstone Press

7a St Lawrence Terrace

London, UK W10 5SU

www.theredstoneshop.com

Compilation 2017 Redstone Press

Introduction Lionel Shriver, 2016

Commentaries Mel Gooding, 2016

Essay Oisn Wall, 2016

ISBN 978-1-61689-492-4 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61689-535-8 (epub, mobi)

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Design: Julian Rothenstein

Copyeditor: Jill Hollis

Artwork: Otis Marchbank Production: Tim Chester

FOR PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS:

Project Editors: Rob Shaeffer and Barbara Darko

Typesetting: Paul Wagner and Mia Johnson

Cover design: Paul Wagner

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the publisher upon request.

IMAGE CREDITS:

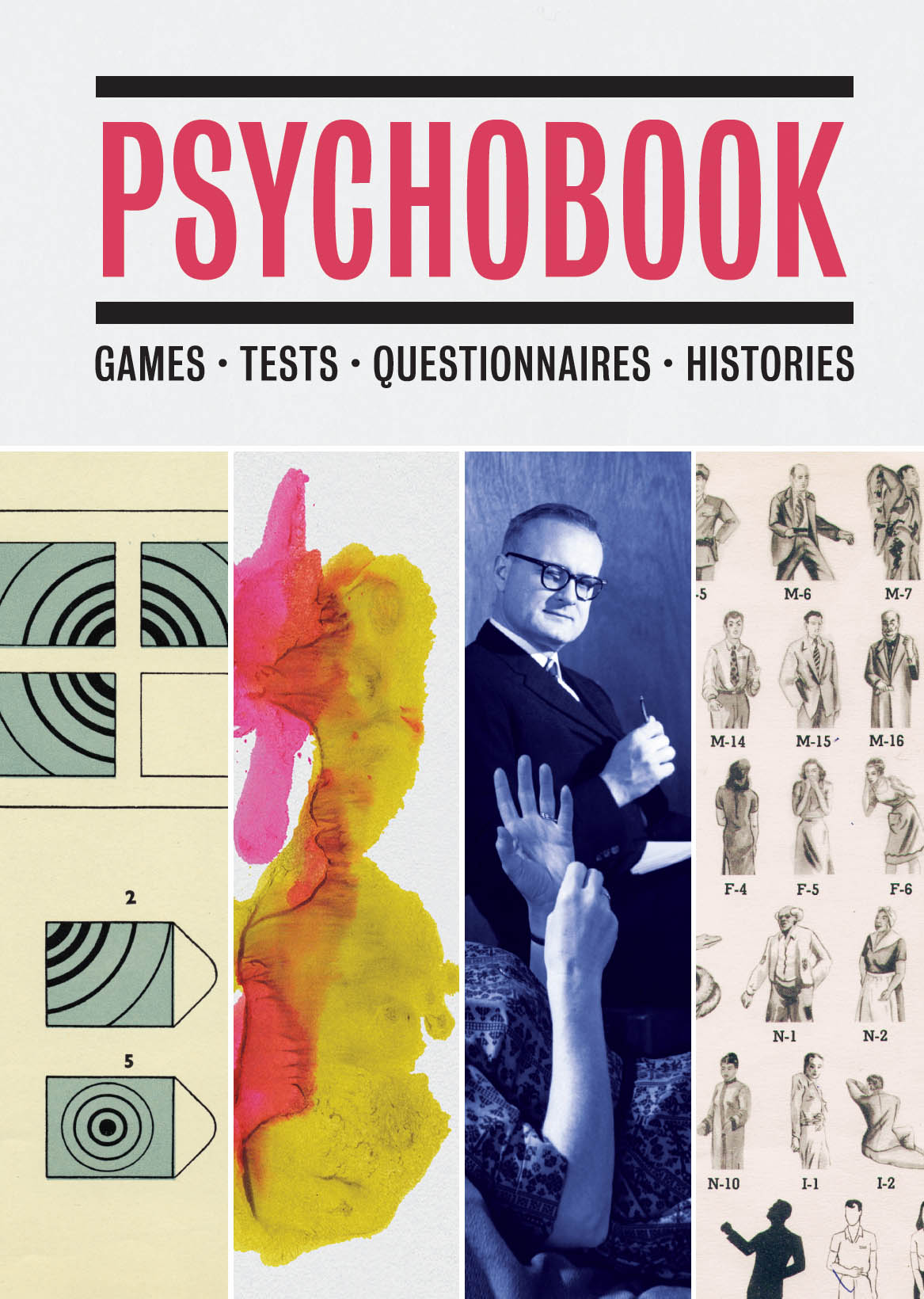

Corbis: front cover center right,

Redstone Press collection: front cover far and center left,

Getty Images:

Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam:

Courtesy of The Freud Museum:

Drawings Adam Dant:

Photographs Sebastian Zimmerman:

Photographs Nick Cunard:

Photomontage with portraits of Sigmund Freud and Kurt Weill by Louise Dahl-Wolfe, ca. 1934

Contents

Introduction

Lionel Shriver

As a kid, I was always befuddled by classmates whose reigning ambition was to fit into blend with their peers as if into human wallpaper. I wanted to stand out. Admittedly, I came of age in the 1960s, an era that celebrated oddity. Yet even during that age of transgressive individualism, most of my contemporaries wanted to keep their heads down. By contrast, I proudly declared that my favorite color was black (and grew bored with people informing me that black is not a color), and that I far preferred overcast skies to sunny days (my father worried there was something wrong with my eyes). At fifteen, every day at school I wore a little black velvet tam, an unfashionable signature I was so afraid of losing that I secured it with a shoelace tucked behind my left ear and safety-pinned to my collar. A good four decades before the rest of the world followed suit, I cycled everywhere I went, refusing to learn to drive when I came of age. Using ineffectual masking tape, I decorated the ceiling of my bedroom with dangling strings of beads, which continually plopped back down on the bedspread. I strode the halls of my Atlanta high school in a homemade sash pinned with my complete political button collectiona source of great hilarity behind my back, Im sure. I was a bit of a nutter, and I wanted to be a nutter.

Thus Ive been naturally hostile to conventional psychological testing, insofar as it is designed to weed out the weirdos from the regular people. In my life, the whole concept of the normal has functioned as a neutral backdrop against which I can loom forward in relief. Of course, throughout my adulthood, the drive to slot everyone into a category, to slap a diagnosis on every variation from the mean, has only accelerated. Indeed, we now live in a time when if you dont have a diagnosis you dont know who you are, and people wave their designated psychiatric ailments like football trophies. With a wealth of new classifications at our disposal, we can easily peg me now: I am an attention seeker. Damn straight. I have sought attention and often got it, if not always the nice kind.

Granted, in adulthood I have repudiated the careless view popular in the 1960s that its the crazy people who are sane, and the sane are crazy. Theres such a thing as crazy, and it isnt pretty; serious mental illness rarely entails access to a higher truth. But then, serious mental illness isnt subtle, either, and therapists contending with a raving schizophrenic dont generally need to resort to questionnaires.

As a novelist, too, I instinctively resist the quantification of character, the reduction of such an elusive concept to a set of measurements, to a score. Theoretically, I suppose, fiction writers might construct protagonists by choosing numerical points on various key continuums: on a scale of one to ten, say, our hero scores two for fearfulness, nine for openness to new experience, one for risk aversion, eight for ego strengthBut good luck with charting out our storys principals in this manner and coming up with Pierre from War and Peace. In other words, even when they are not misleading, the results of much psychiatric testing are crudely descriptive, and tell you little you didnt know before.

Nevertheless, the psychological tests collected in this book are often compelling, if only, especially in the early, more historical instances, compellingly stupid. Some of the statements are comical: I do not like to see men in their pyjamas. Some of the questions invite wistful existential speculation: if asked, Does the future seem pointless? who wouldnt, on some days, say yes? Ditto, Do you feel that there is some sort of barrier between you and other people so that you cant really understand them? Isnt that the standard state of affairs between anybody and anybody? Isnt real intimacy the exception? And the few folks who fail to confess, I do not always tell the truth, are lying, if only to themselves.

Psycho-quizzes are also blind to contextthe specific circumstances that dictate even truthful answers to which the test is oblivious. An air traffic controller might agree, I work under a great deal of tension without having an anxiety disorder. A Nobel laureate might affirm I am an important person without being a narcissist. A well-adjusted subject who concurs It would be better if almost all laws were thrown away obviously lives in the EU. A woman who concedes Once a week or oftener I feel suddenly hot all over without apparent cause may simply be over fifty. These days, those who tick a box beside Are people talking about you and criticizing you through no fault of your own? arent implicitly paranoid; they participate in social media. Likewise, a tick next to Someone has been trying to get into my car means something different depending on the neighborhood where the car has been parked. Were I to check, Once in a while I think of things too bad to talk about, it would help the test giver to know that I write novels and thinking abominations is my job.

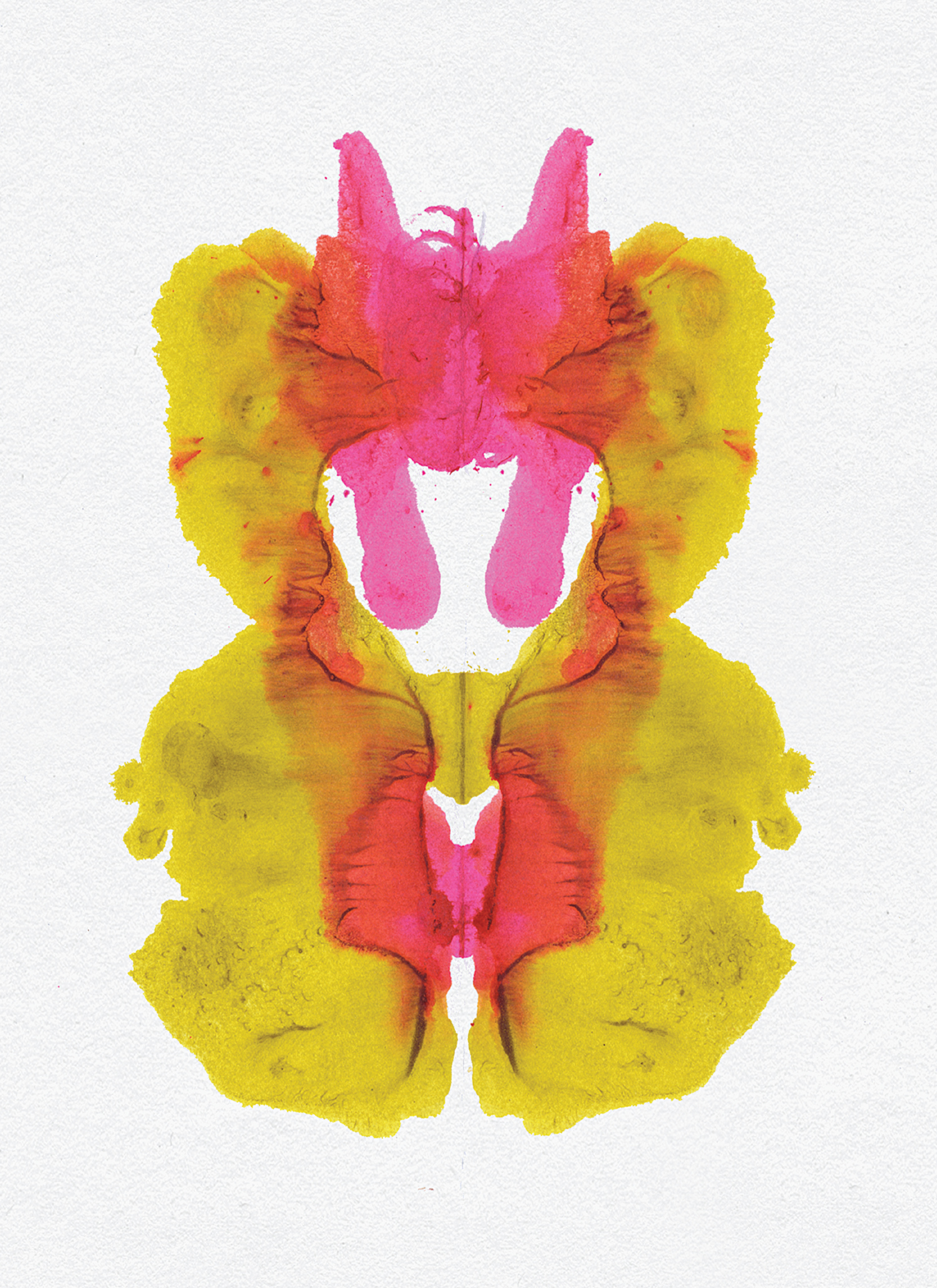

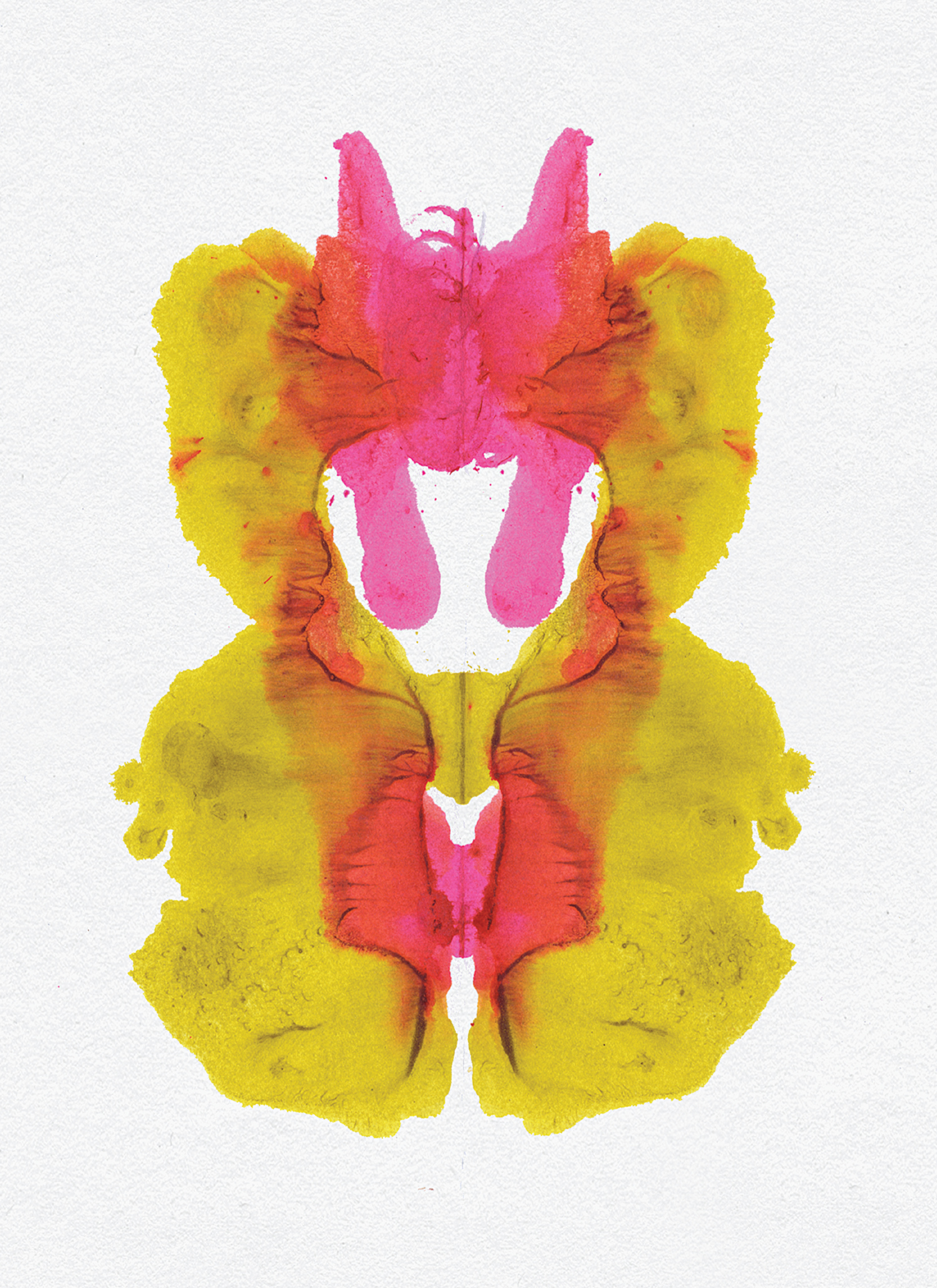

Whats especially stupid about much psychological testing is that the psychologists think were stupid. That is, the test designers fail to give subjects credit for being able to intuit the purpose of the test, and thus which answers it is in their interest to provide. Even way back when, looking at Rorschach inkblots, half-sussed patients knew perfectly well that they were better off seeing not bats but butterflies. Were you to tick, when taking a personality test as part of a job application, I am afraid I am going out of my mind, you would indeed be out of your mind. One is reminded of those naff American visa applications that ask, Are you a terrorist? And then when jihadists manage to slip through this brutal interrogation anyway, law enforcement is consternated.

Next page