Playful Thinking

Jesper Juul, Geoffrey Long, and William Uricchio, editors

The Art of Failure: An Essay on the Pain of Playing Video Games, Jesper Juul, 2013

Uncertainty in Games, Greg Costikyan, 2013

Play Matters, Miguel Sicart, 2014

Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art, John Sharp, 2015

How Games Move Us: Emotion by Design, Katherine Isbister, 2016

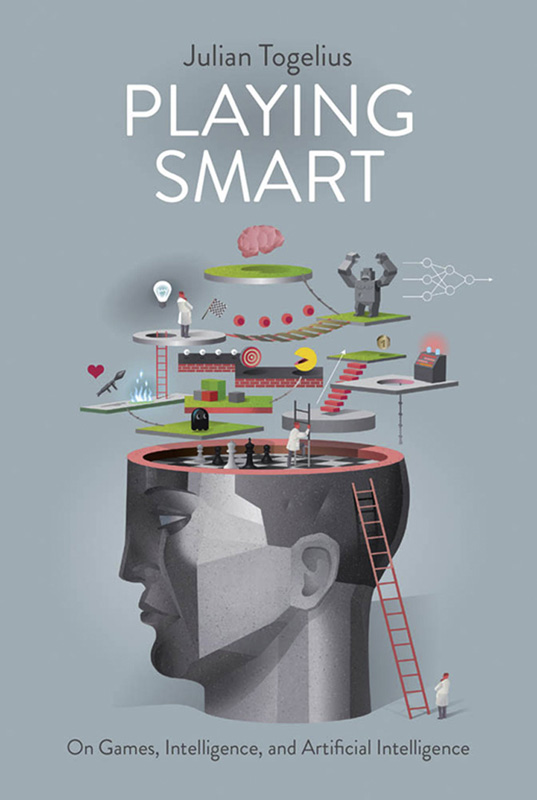

Playing Smart: On Games, Intelligence, and Artificial Intelligence, Julian Togelius, 2018

2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in ITC Stone Serif Std by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Togelius, Julian, author.

Title: Playing smart : on games, intelligence and Artificial Intelligence / Julian Togelius.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, [2018] | Series: Playful thinking | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018010191 | ISBN 9780262039031 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262350136

Subjects: LCSH: Video games--Psychological aspects. | Video games--Design. | Intellect. | Thought and thinking. | Artificial intelligence.

Classification: LCC GV1469.34.P79 T64 2018 | DDC 794.8--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018010191

ePub Version 1.0

Table of Contents

List of tables

List of figures

Guide

On Thinking Playfully

Many people (we series editors included) find video games exhilarating, but it can be just as interesting to ponder why that is so. What do video games do? What can they be used for? How do they work? How do they relate to the rest of the world? Why is play both so important and so powerful?

Playful Thinking is a series of short, readable, and argumentative books that share some playfulness and excitement with the games that they are about. Each book in the series is small enough to fit in a backpack or coat pocket, and combines depth with readability for any reader interested in playing more thoughtfully or thinking more playfully. This includes, but is by no means limited to, academics, game makers, and curious players.

So we are casting our net wide. Each book in our series provides a blend of new insights and interesting arguments with overviews of knowledge from game studies and other areas. You will see this reflected not just in the range of titles in our series, but in the range of authors creating them. Our basic assumption is simple: video games are such a flourishing medium that any new perspective on them is likely to show us something unseen or forgotten, including those from such unconventional voices as artists, philosophers, or specialists in other industries or fields of study. These books are bridge builders, cross-pollinating both areas with new knowledge and new ways of thinking.

At its heart, this is what Playful Thinking is all about: new ways of thinking about games and new ways of using games to think about the rest of the world.

Jesper Juul

Geoffrey Long

William Uricchio

Prologue: AI&I

I was eleven when my cats had to be given away because my mother had discovered she was allergic to them. Of course, I was very sad about the departure of my cats, but not so much that I wouldnt accept a Commodore 64 as a bribe to not protest too loudly. The Commodore 64 was already an obsolete computer in 1990; now, operational Commodore 64s are mostly owned by museums and hipsters.

I quickly became very engrossed in my Commodore 64, more than I had been in my cats, because the computer was more interactive and understandable. Or rather, there was the hint of a possibility to understand it. I played the various games that I had received with the computer on about a dozen cassette tapesloading a game could take several minutes and frequently failed, testing the very limited patience of an eleven-year-oldand marveled at the depth of possibilities contained within those games. Although I had not yet learned how to program, I knew that the computer obeyed strict rules all the way and that there was really no magic to it, and I loved that. This also helped me see the limitations of these games. It was very easy to win some games by noticing that certain actions always evoked certain responses and certain things always happened in the same order. The fierce and enormous ant I battled at the end of the first level in Giana Sisters really had an extremely simple pattern of actions, limited by the hardware of the time. But that did not lessen my determination to get past it.

You could argue that the rich and complex world of these games existed as much in my imagination as in actual computer memory. I knew that the ant boss in Giana Sisters moved just two steps forward and one step backward regardless of what I did, or that the enemy spaceships in Defender simply moved in a straight line toward my position wherever I was on the screen. But I wanted there to be so much more. I wanted there to be secret, endless worlds to explore within these games, characters with lives of their own, a never-emptying treasure trove of secrets to discover. Above all, I wanted there to be things happening that I could not predict, but which still made sense for whoever inside the game made them happen.

In comparison, my cats were mostly unpredictable and gave every sign of living a life of their own that I knew very little about. But sometimes they were very predictable. Pull a string, and the cat would jump at it; open a can of cat food, and the cat would come running. After spending time among the rule-based inhabitants of computer games, I started wondering whether the cats behaviors could be explained the same way. Were their minds just sets of rules specifying computations? And if so, was the same thing true for humans?

Because I wanted to create games, I taught myself programming. I had bought a more capable computer with the proceeds from a summer job when I was thirteen and found a compiler for the now-antiquated programming language Turbo Pascal on that computers hard drive. I started by simply modifying other peoples code to see what happened until I knew enough to write my own games. I rapidly discovered that making good games was hard. Designing games was hard, and creating in-game agents that behaved in an even remotely intelligent manner was very hard.

After finishing high school I did not want to do anything mathematical (I was terrible at math and hated it). I wanted to understand the mind, so I started studying philosophy and psychology at Lund University. I gradually realized, however, that to really understand the mind, I needed to build one, so I drifted into computer science and studied artificial intelligence. For my PhD, I was, in a way, back to animals. I was interested in applying the kind of mechanisms we see in simple animals (the ones that literally dont have that many brain cells) to controlling robots and also in using simulations of natural evolution to learn these mechanisms. The problem was that the experiments I wanted to do would require thousands or even tens of thousands of repetitions, which would take a lot of time. Also, real robots frequently break down and require service, so these experiments would need me to be on standby as a robot mechanic, something I was not interested in. Physical machines are boring and annoying; its the ideas behind them that are exciting.

![Ethan Ham [Ethan Ham] - Tabletop Game Design for Video Game Designers](/uploads/posts/book/119417/thumbs/ethan-ham-ethan-ham-tabletop-game-design-for.jpg)