BIRTH OF THE SYMBOL

BIRTH OF THE SYMBOL

AN

CIENT READERS AT THE LIMITS

OF

THEIR TEXTS

Peter T. Struck

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

COPYRIGHT 2004 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET,

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE,

WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

STRUCK, PETER, 1965

BIRTH OF THE SYMBOL : ANCIENT READERS AT THE LIMITS OF THEIR TEXTS /

PETER STRUCK.

P.CM.

BASED ON AUTHORS THESIS (DOCTORAL)UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO.

INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES (P.) AND INDEX.

eISBN: 978-1-40082-609-4

1. CLASSICAL POETRYHISTORY AND CRITICISM. 2. SYMBOLISM IN

LITERATURE. 3. BOOKS AND READINGGREECE. 4. BOOKS AND READING

ROME. 5. RHETORIC, ANCIENT. 6. ALLEGORY. I. TITLE.

PA3021.S76 2004

881.010915DC21 2003048609

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN SABON

PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER.

WWW.PUPRESS.PRINCETON.EDU

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Natalie and Adam

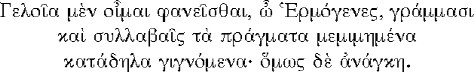

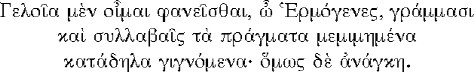

I suppose it will appear laughable, Hermogenes, that things are made manifest by imitation in letters and syllables. Nevertheless, it must be so.

Plato Cratylus 425d

C O N T E N T S

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS

BOOK began as a dissertation at the University of Chicago. I have been generously supported for research and travel by the University of Chicago, the Whiting Foundation, Ohio State University, the University of Missouri at Kansas City, the University of Pennsylvania, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the National Humanities Center, where I was Robert F. and Margaret S. Goheen Fellow (20023). For their generous guidance and inspiration I would like to thank Christopher Faraone, W. Ralph Johnson, Sarah Iles Johnston, Elizabeth Asmis, Franoise Meltzer, Walter Burkert, Anthony C. Yu, Ineke Sluiter, W. Robert Connor, Mark Usher, and Natalie Dohrmann. I have also learned a great deal from brief conversations with Stephen Gersh, Glenn Most, and Dirk Obbink, whose critical reactions to various sections of this work have spurred me to reconsiderations on several levels. T. J. Wellman and Kevin Tracy provided invaluable help in preparation of the manuscript. But thanks are due especially to Michael Murrin, magister doctissimus, whose influence will be apparent to all who have been lucky enough to have worked with him.

BIRTH OF THE SYMBOL

INTRODUCTION

THE GENEALOGY OF THE SYMBOLIC

TH

IS STUDY EXAMINES the ancient history of an idea, or per-haps it is better called a hope or desire. What do we expect from poetry? Is it an entertaining diversion? An edifying tale? A craft whose masters delight and move us with their elegance and fine workmanship? Yes, perhaps. But a few bold souls, ancient as well as modern, have it in mind that poetry will do something more for us. They suspect that the poets stories might say more than they appear to say, and that their language might be more than just words. Though these readers are likely to concede that the poets work with the mundane stuff of everyday speech, they still hear in their words the faint but distinct promise of some truer resonance, of a subtle and profound knowledge that arrives in a concealed form and is waiting for a skilled reader to liberate it from its code. Some go further and take poetry as a vehicle into a region where more sober minds fear to tread, where the limitations and encumbrances of our regular lives do not exist, and where we might meet, finally face to face, the deathless gods themselves. This realm is familiar to most of us, as a superstition or a moment of insight. It lies just beyond the always receding horizon that circumscribes our day-to-day existence. Though some say it is only a phantom, others are equally sure that it exists and are drawn away by its Siren song toward what they have learned from tantalizing daily experience to be always just out of reach. With a certain regularity, ancient readers find passage to this realm by the same means. They are transported by what they understand to be the inspired poets most profound and most deeply resonant poetic creations, which they mark with the same Greek term,

, or symbols.

, or symbols.

The symbol has a familiar enough standing in contemporary thinking on literature. In most standard reference works, a symbol is a deeply resonant literary image thought to have some special linkage with its meaning: the word organic frequently appears in its various definitions. We owe to the Romantics the symbols modern apotheosis into the role of master literary device. As I will discuss in my concluding chapter, the modern symbol is connected with its ancient legacy, but only through a circuitous and difficult route. This study attempts to retrace the oldest segments of this path. In order to do so, we will pass through an overgrown tangle of debates and discussions, problems and possibilities, cosmologies, theologies, and metaphysical schemes that have long since lost their relevanceand yet whose concerns, motivations, and agendas endure, even to this day, in and through the category of symbolic language. With this in mind, I consider what I present here to be a genealogy, of sorts, of classical notions of the symbol, insofar as they are relevant to its history in literary commentary.

A historian focusing on the large body of texts and scholarship that in recent tradition constitutes the field of classical literary criticism will be tempted to conclude that the symbol is a foundling in the history of criticism, as though it arrived a fully formed orphan on the doorstep of the modern age in the late 1700s. As opposed to metaphor (Greek

Next page

, or symbols.

, or symbols.