What I Believe

Three passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.

Bertrand Russell

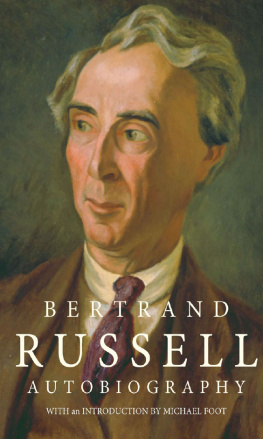

Bertrand Russell is regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century and a celebrated writer and commentator on social and political affairs. The grandson of twice Prime Minister Lord John Russell, Bertrand Russell was born in 1872 in Trellech, Wales. Both his parents died whilst Russell was in infancy, leaving him to be brought up by his grandparents in London. He gained a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, which he began in 1890. Following outstanding results in mathematics and philosophy he became a Fellow in philosophy in 1895. In 1903 he published The Principles of Mathematics, arguing that mathematics rested on a very small number of basic principles. In 1905 he wrote his famous paper On Denoting, which was to become a founding document in the philosophy of language and logic. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1908. The first of three volumes of Principia Mathematica, written with Alfred North Whitehead, was published in 1910 and in the same year, aged 38, Russell became a lecturer at the University of Cambridge.

During the First World War, Russell devoted much of his time to the cause of pacifism. He found himself dismissed from his post at Cambridge in 1916 as a result. He was also imprisoned for six months in 1918 for publicly lecturing against Britian's invitation that the United States enter the War. Russell then visited the United States, first teaching at the University of Chicago before moving to UCLA in Los Angeles. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York in 1940, but after protests over Russell's liberal views on religion and marriage the appointment was annulled in court. He returned to Britain in 1944 to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College. During the 1940s and 1950s, Russell's oratory skills were heard on many BBC broadcasts, particularly The Brains Trust, where he spoke, with his customary acuity, on various topical and philosophical subjects. In 1948, Russell was invited by the BBC to deliver the inaugural Reith Lecture.

The 1950s and 1960s again saw Russell engaged in pacifist work, primarily related to nuclear disarmament and opposing the Vietnam War. The 1955 Russell-Einstein Manifesto called for nuclear disarmament and was signed by eleven of the most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the day. Russell continued to write and his celebrated Autobiography was published in three volumes between 1967 and 1969. He died in 1970 and was cremated in Colwyn Bay, Wales, near his home. His ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains.

Alan Ryan was born in London in 1940 and taught for many years at Oxford, where he was a Fellow of New College and Reader in Politics. He was Professor of Politics at Princeton from 1988 to 1996, when he returned to Oxford to become Warden of New College and Professor of Political Theory until his retirement in 2009. His previous books include The Philosophy of John Stuart Mill, Bertrand Russell: A Political Life and John Dewey and the High Tide of American Liberalism. He is a Fellow of the British Academy.

Leonardo da Vinci by Sigmund Freud

Letter to a Priest by Simone Weil

Myth and Meaning by Claude Lvi-Strauss

Relativity by Albert Einstein

On Dialogue by David Bohm

Sketch for a Theory of the Emotions by Jean-Paul Sartre

The Sovereignty of Good by Iris Murdoch

The Undiscovered Self by Carl Gustav Jung

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein

What I Believe by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand

Russell

What I Believe

First published 1925

by Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner & Co Ltd, London

First published in Routledge Classics 2004

by Routledge

This edition published in Routledge Great Minds 2014

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1996 The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation Ltd

2004, 2014 foreword, Alan Ryan

Typeset in Joanna by RefineCatch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted

or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic,

mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter

invented, including photocopying and recording, or in

any information storage or retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-415-85476-4 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-88959-7 (ebk)

CONTENTS

This Routledge Great Minds edition of What I Believe contains a foreword by Alan Ryan that first appeared as a preface in the Routledge Classics edition published in 2004. Included in this edition are two essays by Russell that do not appear in the Routledge Classics edition, Why I Took to Philosophy and How I Write.

Fifty years after reading Bertrand Russell for the first time, I read him today with mixed feelings. In the middle 1950s, his History of Western Philosophy was a treat to teenage schoolboys bored to death with the slog of O Level. It gave us all the weapons we needed to torment the school chaplain when he tried to explain to agnostic teenagers Aquinas's Five Ways to the knowledge of God's existence. Why I am not a Christian was an even more valuable weapon against authority. My housemaster's belief that Russell's four marriages discredited his views on sex, God and nuclear warfare only confirmed my view that most holders of authority were bigoted, illogical and not to be taken seriously.

I have not wholly changed my mind. Russell's four marriages are irrelevant to his views on sex, God and nuclear warfare; I now think that his marital difficulties should have made him more wary about making the pursuit of happiness look easy, but his ideas about what the good life is wear well. He had many vices as a critic of views he disliked, and his practice was at odds with his professed principle of taking on one's opponents at their strongest points rather than their weakest. In those ways, he was less admirable than John Stuart Mill. On the other hand, he was, and is, much more fun. In particular, he wrote wonderfully; even the articles he turned out for the Hearst newspapers at fifty dollars a pop, in order to support Beacon Hill, the school that he and his second wife had created, are not only quick and clever, but thought-provoking too. If Britain took literacy seriously, teenagers would be given Russell as a model essayist.

During the First World War Russell realized that he had an extraordinary talent for lecturing to lay audiences. He was deeply opposed to the war and, as a member of the Union for Democratic Control early in the war and later as a leading figure in the No-Conscription Fellowship, he worked unceasingly to bring the war to an early end, to persuade the United States to remain neutral, and to protect conscientious objectors from abuse at the hand of the tribunals that heard their case for exemption, and from ill-treatment in prison or the army, if they ended up there. These activities cost him his lecturership at Trinity College, Cambridge, but they brought him into a new world, too.

Next page