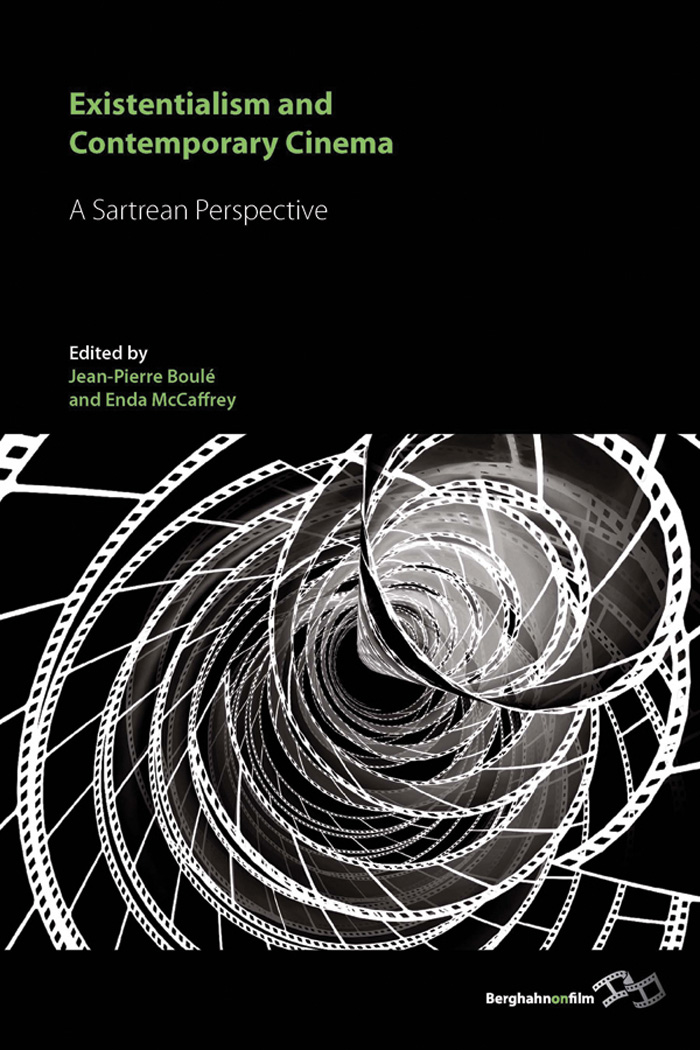

EXISTENTIALISM AND CONTEMPORARY CINEMA

EXISTENTIALISM AND

CONTEMPORARY CINEMA

A Sartrean Perspective

Edited by

Jean-Pierre Boul and Enda McCaffrey

NEW YORK OXFORD

www.berghahnbooks.com

Published in 2011 by

Berghahn Books

www.berghahnbooks.com

2011, 2014 Jean-Pierre Boul and Enda McCaffrey

First paperback edition published in 2014

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of Berghahn Books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Existentialism and contemporary cinema : a Sartrean perspective / edited by Jean-Pierre Boul and Enda McCaffrey.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-85745-320-4 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-78238-494-6 (paperback) -- ISBN 978-0-85745-321-1 (ebook)

1. Existentialism in motion pictures. 2. Philosophy in motion pictures. 3. Sartre, Jean-Paul, 1905-1980--Philosophy. 4. Sartre, Jean-Paul, 1905-1980--Influence. I. Boul, Jean-Pierre. II. McCaffrey, Enda.

PN1995.9.E945E94 2011

791.43684--dc23

2011019539

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed on acid-free paper

ISBN: 978-0-85745-320-4 hardback

ISBN: 978-1-78238-494-6 paperback

ISBN: 978-0-85745-321-1 ebook

CONTENTS

Introduction

Jean-Pierre Boul and Enda McCaffrey

Chapter 1 Peter Weirs The Truman Show and Sartrean Freedom

Christopher Falzon

Chapter 2 Michael Haneke and the Consequences of Radical Freedom

Kevin L. Stoehr

Chapter 3 Naked, Bad Faith and Masculinity

Mark Stanton

Chapter 4 Pursuits of Transcendence in The Man Who Wasnt There

Tom Martin

Chapter 5 Lornas Silence: Sartre and the Dardenne Brothers

Sarah Cooper

Chapter 6 Being Lost in Translation

Michelle R. Darnell

Chapter 7 If I Should Wake Before I Die: Existentialism as a Political 111 Call to Arms in The Crying Game

Tracey Nicholls

Chapter 8 Crimes of Passion, Freedom and a Clash of Sartrean Moralities in the Coen Brothers No Country for Old Men

Enda McCaffrey

Chapter 9 An Act of Confidence in the Freedom of Men: Jean-Paul Sartre and Ousmane Sembene

Patrick Williams

Chapter 10 Cdric Klapischs The Spanish Apartment and Russian Dolls 157 in Nauseas Mirror

Jean-Pierre Boul

Chapter 11 Baz Luhrmanns William Shakespeares Romeo + Juliet: The Nauseous Art of Adaptation

Alistair Rolls

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our colleagues Matt Connell and Martin OShaughnessy, the Editorial Manager at Berghahn Books, Mark Stanton, and all our contributors for their patience and diligence.

INTRODUCTION

Movies exercise a hold on us, a hold that, drawing on our innermost desires and fears, we participate in creating. To know films objectively, we have to know the hold they have upon us. To know the hold films have on us, we have to know ourselves objectively. And to know ourselves objectively, we have to know the impact of films on our lives. No study of film can claim intellectual authority if it is not rooted in self-knowledge, our knowledge of our own subjectivity. In the serious study of film, in other words, criticism must work hand in hand with the perspective of self-reflection that only philosophy is capable of providing.

(Rothman and Keane 2000: 1718)

At the heart of this volume is the understanding that Sartrean existentialism, most prominent in the 1940s particularly in France, is still relevant as a way of interpreting the world today. And film, by reflecting philosophical concerns in the actions and choices of characters, continues and extends a tradition in which art exemplifies the understanding of this philosophy. This book, therefore, seeks to revalidate the Sartrean philosophical project through its application to film.

I am an existentialist. What does this statement mean? What kind of existentialism is one talking about? There are a variety of philosophical tenets held by those who call themselves existentialists, some of whom are phenomenologists, a philosophy that deals with consciousness and that goes back to the things themselves, asking the question: what does existing mean? Existentialism is a philosophy derived from the Danish and German philosophers Kierkegaard and Heidegger; the former was Christian and the latter an atheist. In France, the philosopher Gabriel Marcel was influenced by the ideas of Kierkegaard and Jean-Paul Sartre (whose existentialism is the primary focus of this volume) by the ideas of Heidegger. William Shearson, in highlighting the differences amongst philosophers who would define themselves as existentialists, defines existentialism as based on two principles: knowledge that is gained through experience, and the self defined not as substance but as a lived relation to that which situates it (Shearson 1975: 135, 138).

Existentialism emerged in France at the end of the Second World War, which had seen France occupied by Germany (see McBride 1996; Webber 2008). A philosophy of freedom and responsibility resonated particularly in France and in Western Europe before crossing the Atlantic and finding an echo in North America which had also suffered from the war. This context is paramount to the success of Sartrean existentialism in France (Boschetti 1985; Galster 2001). After the end of the Second World War, as Sartre became more prominent in the media, he was continually asked to explain existentialism (Boul 1992). Sartre says that existentialism is a doctrine according to which existence precedes essence (and not the converse which would be the definition of determinism). His thesis is that human beings exist first and in choosing themselves, they create themselves. In acting, they define themselves; in short, therefore, there is no difference between being and doing. Furthermore, human beings acts and choices are always defined within a given situation, and within that situation (which is simply one of the aspects of the human condition) human beings are free and therefore responsible.

In most newspaper articles and interviews at the time, Sartre explained existentialism in terms one can find in his work Existentialism Is a Humanism. This slim and accessible volume started as a public lecture given on 29 October 1945 which the publisher Nagel published as a small booklet in 1946. It was only ever intended as a lecture designed on the one hand to popularise Sartres thought and on the other hand to respond to accusations from French Communists and Christians alike that his philosophy was having a corrupting influence on French youth. Existentialism Is a Humanism does not represent a complete picture of Sartrean philosophy (Keefe 1972). As an early insight into Sartres thinking, it is a condensed version of his existentialist philosophy which is why it was chosen as the key reference text for all contributors to this collection. It is inevitable, therefore, that some central existentialist themes will be repeated across chapters. This adds focus to the volume and should not detract from the originality of each chapter, conceived as each is to stand alone on its own merits.