A M IDDLE E NGLISH R EADER AND A M IDDLE E NGLISH V OCABULARY A M IDDLE E NGLISH R EADER Edited by KENNETH SISAM AND A M IDDLE E NGLISH V OCABULARY J. R. R. TOLKIEN TWO VOLUMES BOUND AS ONE D OVER P UBLICATIONS , I NC . M INEOLA , N EW Y ORK Bibliographical Note This Dover edition, first published in 2005, is an unabridged republication of two volumes bound as one: Volume One (A Middle English Reader) was originally published in 1921 by Oxford at the Clarendon Press under the title Fourteenth Century Verse & Prose; Volume Two (A Middle English Vocabulary), which begins on page 293 of this reprint, was originally published in 1922 by Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fourteenth century verse & prose. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fourteenth century verse & prose.

A Middle English reader / edited by Kenneth Sisam. And A Middle English vocabulary / J.R.R. Tolkien. p. cm. First work originally published: Fourteenth century verse & prose.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921. 2nd work originally published: Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. eISBN 13: 978-0-486-13141-2 1. English literatureMiddle English, 11001500. 2.

English languageMiddle English, 11001500Glossaries, vocabularies, etc. 3. English languageMiddle English, 11001500Readers. I. Sisam, Kenneth. II.

Tolkien, J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel), 18921973. Middle English vocabulary. Title. Title.

PR1120.S55 2005 427.02dc22 2004061802 Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501 CONTENTS  INTRODUCTION I Two periods of our early history promise most for the future of English literaturethe end of the seventh with the eighth century; the end of the twelfth century with the thirteenth. In the first a flourishing vernacular poetry is secondary in importance to the intellectual accomplishment of men like Bede and Alcuin (to name only the greatest and the last of a line of scholars and teachers) who, drawing their inspiration from Ireland and still more from Italy direct, made all the knowledge of the time their own, and learned to move easily in the disciplined forms of Latin prose. During the second the impulse again came from without. In twelfth-century France the creative imagination was set free. In England, which from the beginning of the tenth century had depended more and more on France for guidance, the nobles, clergy, and entertainers, in whose hands lay the fortunes of literature, had a community of interest with their French compeers that has never since been approached.

INTRODUCTION I Two periods of our early history promise most for the future of English literaturethe end of the seventh with the eighth century; the end of the twelfth century with the thirteenth. In the first a flourishing vernacular poetry is secondary in importance to the intellectual accomplishment of men like Bede and Alcuin (to name only the greatest and the last of a line of scholars and teachers) who, drawing their inspiration from Ireland and still more from Italy direct, made all the knowledge of the time their own, and learned to move easily in the disciplined forms of Latin prose. During the second the impulse again came from without. In twelfth-century France the creative imagination was set free. In England, which from the beginning of the tenth century had depended more and more on France for guidance, the nobles, clergy, and entertainers, in whose hands lay the fortunes of literature, had a community of interest with their French compeers that has never since been approached.

So England shared early in the break with tradition; and during the thirteenth century the native stock is almost hidden by the brilliant growth of a new graft. Every activity of the mind was quickened. A luxuriant invention of forms distinguished the Gothic style in architecture. All the decorative arts showed a parallel enrichment. Oxford (at least to insular eyes) was beginning to rival Paris in learning, and to contribute to the over-production of clerks which at first extended the province of the Church, and finally, by breaking the bounds set between ecclesiastics and laymen, played an important part in the secularization of letters. The friars, whose foundation was the last great reform of the mediaeval Church, were at the height of their good fame; and one of them, the Franciscan Roger Bacon, by his work in philosophy, criticism, and physical science, raised the name of English thinkers to an eminence unattained since Bede.

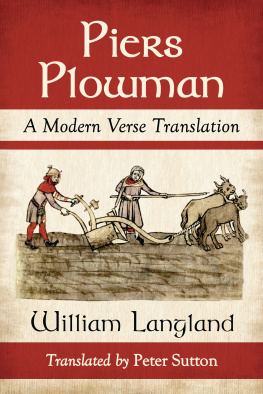

If among the older monastic orders feverish and sometimes extravagant reforms are symptoms of decline, the richness of Latin chronicles like those of Matthew Paris of St. Albans is evidence that in some of the great abbeys the monks were still learned and eloquent. Nor was Latin the only medium in which educated Englishmen were at home. They wrote French familiarly, and to some extent repaid their debt to France by transcribing and preserving Continental compositions that would else have perished. Apart from all these activities, the manifestations of a new spirit in English vernacular works are so important, and the break with the past is so sharp, that the late twelfth century and the thirteenth would be chosen with more justice than Chaucers time as the starting-point for a study of modern literature. Then romance was established in English, whether we use the word to mean the imaginative searching of dark places, or in the more general sense of story-telling unhampered by a too strict regard for facts.

Nothing is more remarkable in pre-Conquest works than the Anglo-Saxons dislike of exaggeration and his devotion to plain matter of fact. Here is the account of the whales in the far North that King Alfred received from Ohthere (a Norseman, of course, but it is indifferent):they are eight and forty ells long, and the biggest fifty ells long. Compare with this parsimony the full-blooded description of the griffins in Mandeville: But o griffoun hath the body more gret, and is more strong, anne eight lyouns, of suche lyouns as ben o this half; and more gret and strongere an an hundred egles suche as we han amonges vs, &c., and you have a rough measure of the progress of fiction. To take pleasure in stories is not a privilege reserved for favoured generations: but special conditions had transformed this pleasure into a passion. When Edward I became King in 1272, Western Europe had enjoyed a long period of internal peace, during which national hatreds burnt low. The breaking down of barriers between Bretons and French, Welsh and English, brought into the main stream of European literature the Celtic vein of idealism and delicate fancy.

At the universities, in the Crusades, in the pilgrimages to Rome or Compostella, the nations mingled, each bringing from home some contribution to the common stock of stories; each gaining new experiences of the outside world, fusing them, and repeating them with embellishments. To those who stayed at home came the minstrels in the heyday of their craftthey were freemen of every Christian land who reported whatever was marvellous or amusingand at second hand the colours of the rediscovered world seemed no less brave. It was an age greedy for entertainment that fed a rich sense of comedy on the jostling life around it; and to serve its ideals called up the great men of the pastOrpheus opening the way to fairyland, the heroes of the Trojan war, Alexander; Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table and Merlin the enchanter; Charlemagne with his peersor won back from the shadows not Eurydice alone, but Helen and Criseyde, Guinevere and Ysolde, Rymenhild and Blaunche-flour. While she still claimed to direct public taste, the Church could not be indifferent to the spread of romance. A policy of uniform repression was no longer possible. Her real power to suppress books was ineffective to bind busy tongues and minds; popular movements were assured of a measure of practical tolerance when order competed with order and church with church for the goodwill of the people; and even if the problem had been well defined, a disciplined attitude unvarying throughout all the divisions of the Church was not to be expected when her mantle covered clerks ranging in character from the strictest ascetic to that older Falstaff who passed under the name of Golias and found his own Muse in the tavern, Tales versus facio quale vinum bibo;Nihil possum scribere nisi sumpto cibo;Nihil valet penitus quod ieiunus scribo, Nasonem ost calices carmine raeibo! So it came about that while some of the clergy denounced all minstrels as ministers of Satan, others made a truce with the more honest among them, and helped them to add to their repertories the lives of saints.

Next page

INTRODUCTION I Two periods of our early history promise most for the future of English literaturethe end of the seventh with the eighth century; the end of the twelfth century with the thirteenth. In the first a flourishing vernacular poetry is secondary in importance to the intellectual accomplishment of men like Bede and Alcuin (to name only the greatest and the last of a line of scholars and teachers) who, drawing their inspiration from Ireland and still more from Italy direct, made all the knowledge of the time their own, and learned to move easily in the disciplined forms of Latin prose. During the second the impulse again came from without. In twelfth-century France the creative imagination was set free. In England, which from the beginning of the tenth century had depended more and more on France for guidance, the nobles, clergy, and entertainers, in whose hands lay the fortunes of literature, had a community of interest with their French compeers that has never since been approached.

INTRODUCTION I Two periods of our early history promise most for the future of English literaturethe end of the seventh with the eighth century; the end of the twelfth century with the thirteenth. In the first a flourishing vernacular poetry is secondary in importance to the intellectual accomplishment of men like Bede and Alcuin (to name only the greatest and the last of a line of scholars and teachers) who, drawing their inspiration from Ireland and still more from Italy direct, made all the knowledge of the time their own, and learned to move easily in the disciplined forms of Latin prose. During the second the impulse again came from without. In twelfth-century France the creative imagination was set free. In England, which from the beginning of the tenth century had depended more and more on France for guidance, the nobles, clergy, and entertainers, in whose hands lay the fortunes of literature, had a community of interest with their French compeers that has never since been approached.