The History of the Hobbit

John D. Rateliff

to

Charles B. Elston

&

Janice K. Coulter

Contents

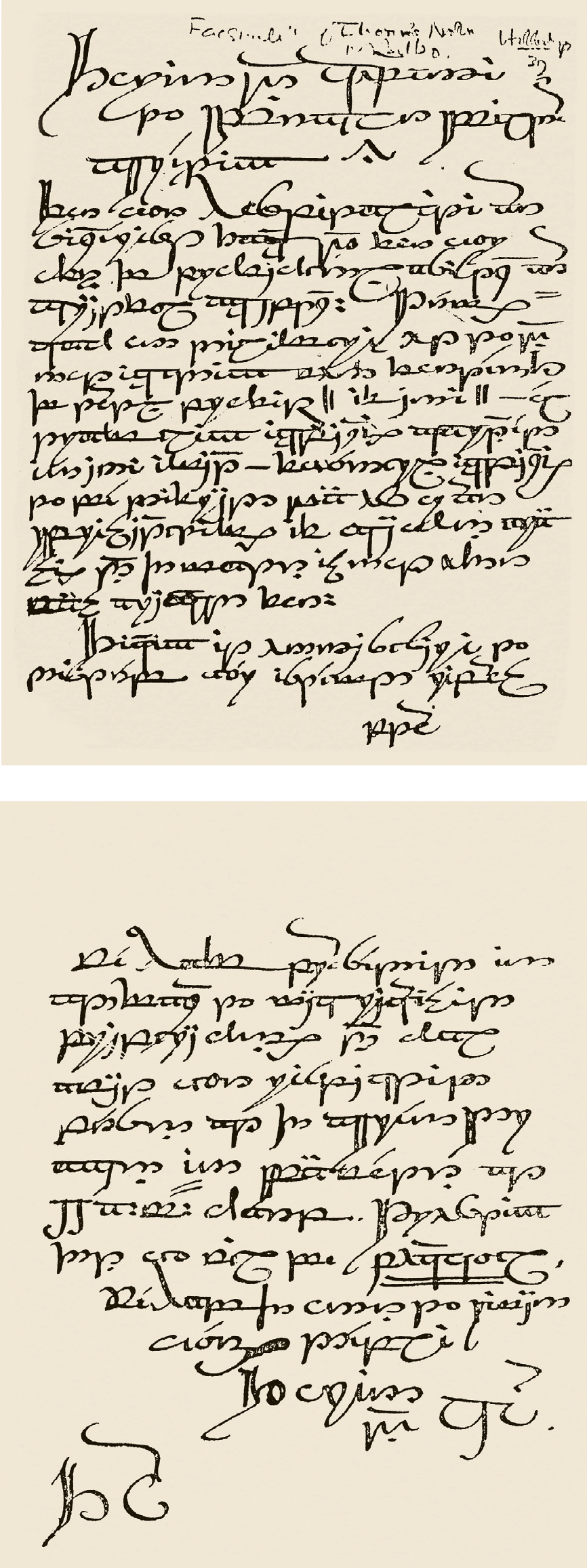

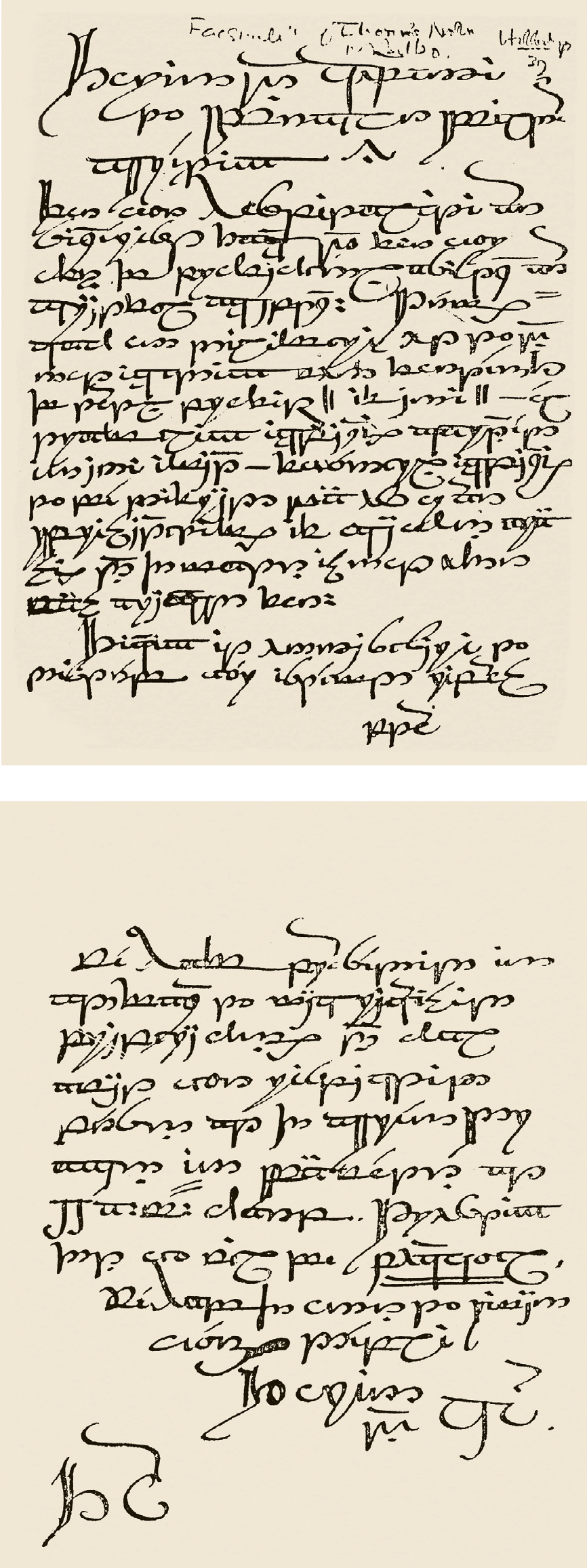

This book offers for the first time a complete edition of the manuscript of J. R. R. Tolkiens The Hobbit , now in the Special Collections and University Archives of Marquette University. Unlike most previous editions of Tolkiens manuscripts, which incorporate all changes in order to present a text that represents Tolkiens final thought on all points whenever possible, this edition tries rather to capture the first form in which the story flowed from his pen, with all the hesitations over wording and constant recasting of sentences that entailed. Even though the original draft strongly resembles the published story in its general outlines and indeed much of its expression, nevertheless the differences between the two are significant, and I have made it my task to record them as accurately as possible.

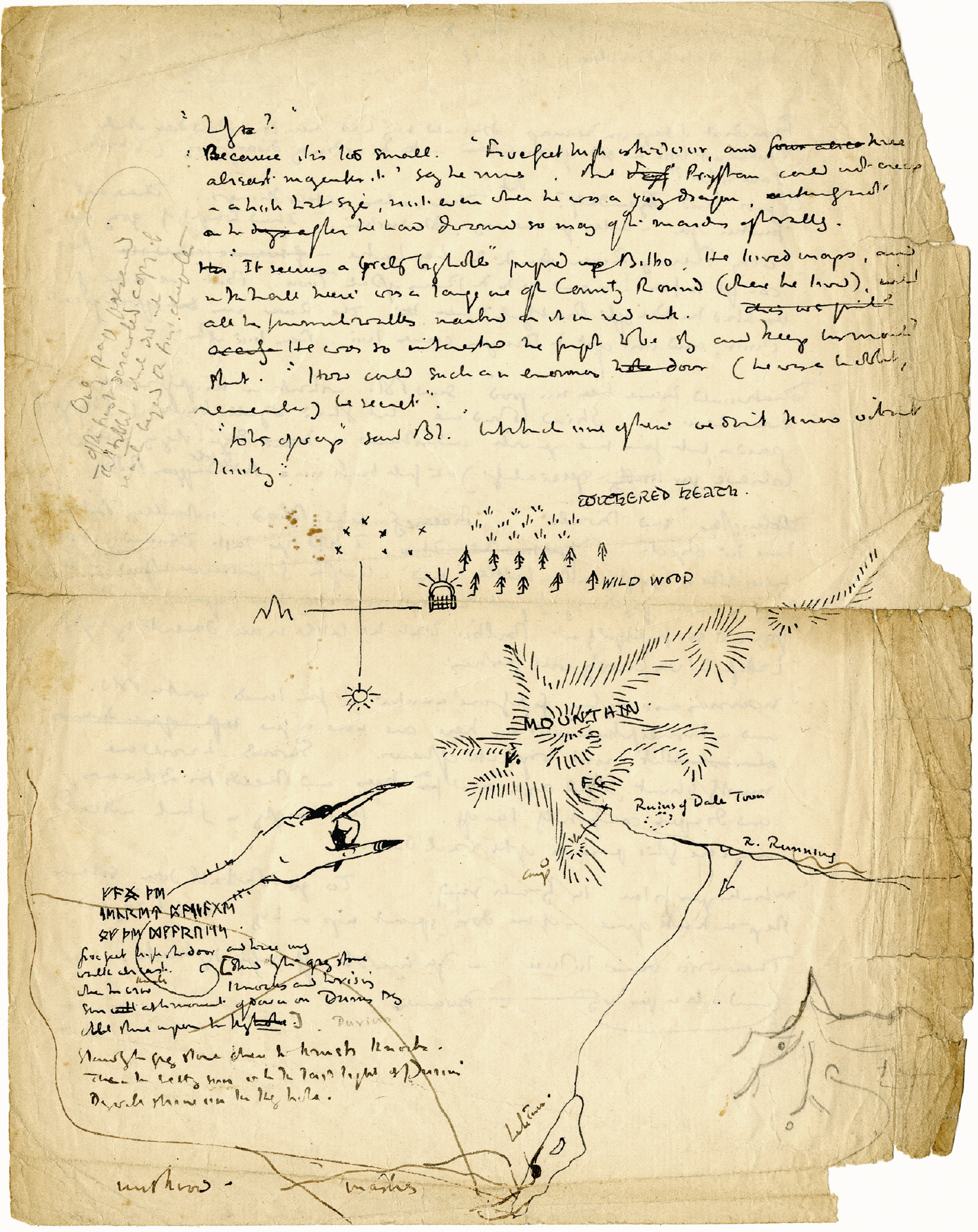

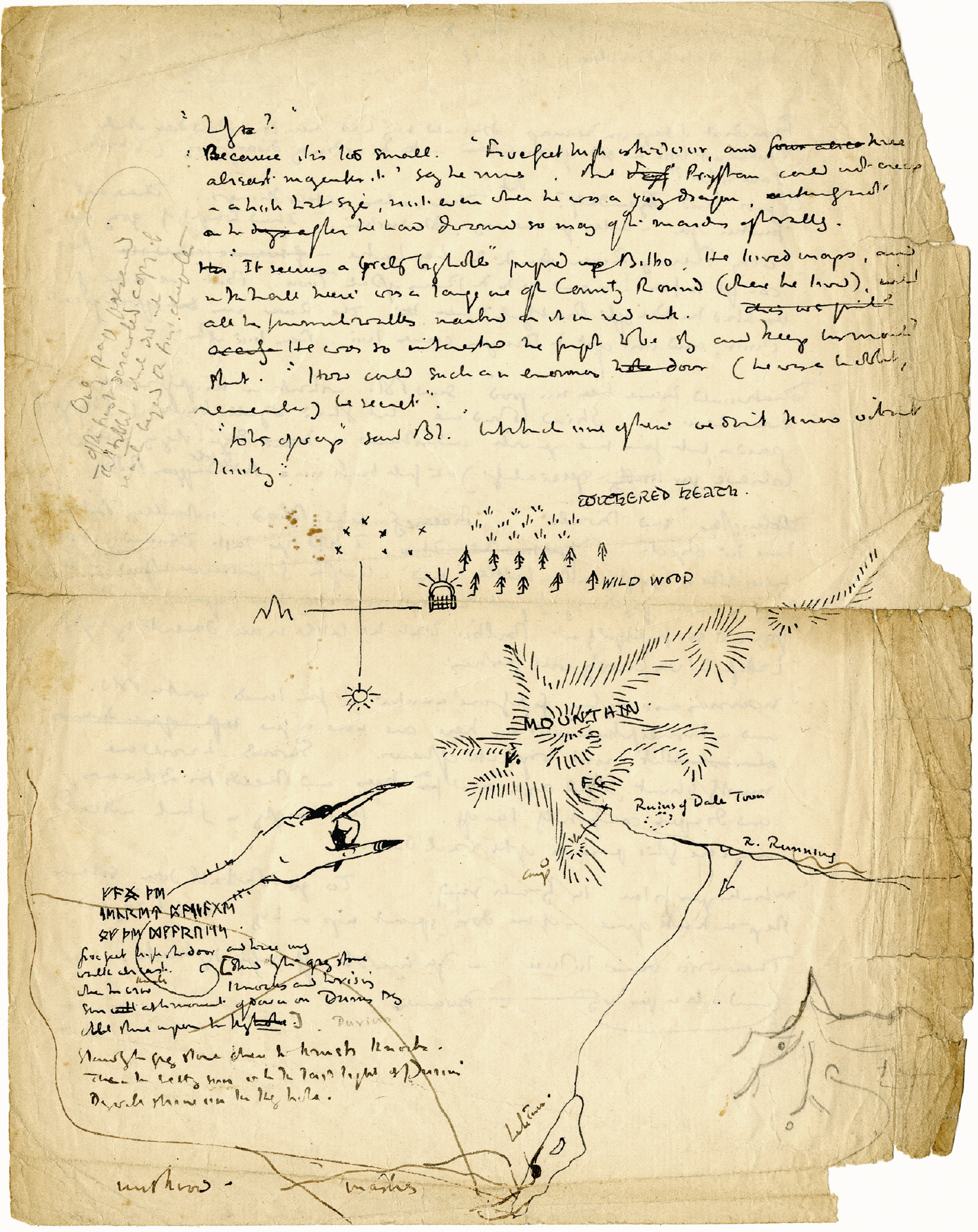

Since the published story is so familiar, it has taken on an air of inevitability, and it may come as something of a shock to see how differently Tolkien first conceived of some elements, and how differently they were sometimes expressed. Thus, to mention a few of the more striking examples, in this original version of the story Gollum does not try to kill Bilbo but instead faithfully shows him the way out of the goblin-tunnels after losing the riddle-contest. The entire scene in which Bilbo and the dwarves encounter the Enchanted Stream in Mirkwood did not exist in the original draft and was interpolated into the story later, at the typescript stage, while their encounter with the Spiders was rewritten to eliminate all mention of a great ball of spider-thread by means of which Bilbo navigated his way, Theseus-like, through the labyrinth of Mirkwood to find his missing companions. No such character as Dain existed until a very late stage in the drafting, while Bard is introduced abruptly only to be killed off almost at once. In his various outlines for the story, Tolkien went even further afield, sketching out how Bilbo would kill the dragon himself, with the Gem of Girion (better known by its later name, as the Arkenstone) to be his promised reward from the dwarves for the deed. The great battle that forms the storys climax was to take place on Bilbos return journey, not at the Lonely Mountain; nor were any of the dwarves to take part in it, nor would Thorin and his admirable (great-) nephews die.

Tolkien was of course superbly skilled at nomenclature, and it can be disconcerting to discover that the names of some of the major characters were different when those characters were created. For much of the original story the wizard who rousts the hobbit from his comfortable hobbit-hole is Bladorthin , not Gandalf, with the name Gandalf belonging instead to the dwarven leader known in the published story as Thorin Oakenshield; the great werebear Gandalf & Company encounter east of the Misty Mountains is Medwed , not Beorn. Other names were more ephemeral, such as Pryftan for the dragon better known as Smaug, Fimbulfambi for the last King under the Mountain, and Fingolfin for the goblin-king so dramatically beheaded by Bullroarer Took. On a verbal level, the chilling cry of Thief, thief, thief! We hates it, we hates it, we hates it for ever! was not drafted until more than a decade after the Gollum chapter had originally been written, and did not make its way into print until seven years after that; the wizards advice to Bilbo and the dwarves on the eaves of Mirkwood was keep your peckers up (rather than the more familiar keep your spirits up that replaced it), and even the final line in the book is slightly different.

Yet, for all these departures, much of the story will still be familiar to those who have read the published version for example, all the riddles in the contest with Gollum are present from the earliest draft of that chapter, all the other dwarves names remain the same (even if their roles are sometimes somewhat different), and Bilbo still undergoes the same slow transformation from stay-at-home-hobbit to resourceful adventuring burglar. In synopsis, the draft and the published book would appear virtually identical, but then Tolkien explicitly warned us against judging stories from summaries (On Fairy-Stories, page 21). With as careful and meticulous an author as Tolkien, details matter, and it is here that the two versions of the story diverge. Think of this original draft as like the unaired pilot episode of a classic television series, the previously unissued demo recordings for a famous album, or the draft score of a beloved symphony. Or, to use a more literary analogy, the relationship between this draft and the published book is rather like that between Caxtons incunabulum Le Morte DArthur and the manuscript of the same work, discovered in 1934, known as the Winchester Malory. In both cases, it is the professionally published, more structured form of the book which established itself as a classic, while the eventual publication of something closer to what the author first wrote reveals a great deal about how the book was originally put together, what its authors intentions were, and more about its affinities with its sources, particularly when (in the case of The Hobbit ) those sources are Tolkiens own earlier unpublished works. That Tolkien himself in this case was responsible for establishing the polished final text does not obscure the fact that here we have two different versions of the same story, and rediscovering the earlier form casts new light on the familiar one. In the words of Tolkiens classic essay On Fairy-Stories,

Recovery... is a re-gaining... of a clear view... We need... to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of... familiarity... Of all faces those of our familiares [intimates, familiars] are the ones... most difficult really to see with fresh attention, perceiving their likeness and unlikeness... [T]he things that are... (in a bad sense) familiar are the things that we have appropriated... We say we know them. They have become like the things which once attracted us... and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring ceased to look at them.

OFS.534.

This need for Recovery is particularly apt in the case of The Hobbit , which in recent years has come to be seen more and more as a mere prelude to The Lord of the Rings , a lesser first act that sets up the story and prepares the reader to encounter the masterpiece that follows. Such a view does not do justice to either book, and ignores the fact that the story of Bilbos adventure was meant to be read as a stand-alone work, and indeed existed as an independent work for a full seventeen years before being joined by its even more impressive sequel. I hope that this edition may serve as a means by which readers can see the familiar book anew and appreciate its power, its own unique charm, and its considerable artistry afresh.

(i)

Chronology of Composition

In a Hole in the Ground

The story is now well known of how, one day while grading student exams, Tolkien came across a blank page in one exam book and on the spur of the moment wrote on it in a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. This scrap of paper is now lost and what survives of the earliest draft is undated, but Tolkien recounted the momentous event several times in interviews and letters; by assembling all the clues from these recollections into a composite account, we can establish the chronology of composition with relative certainty.

Next page