THE HOBBIT PARTY

Jonathan Witt and Jay W. Richards

The Hobbit Party

The Vision of Freedom That Tolkien Got

and the West Forgot

Foreword by James V. Schall, S.J.

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Cover photograph by Eva G. Muntean

Cover design by John Herreid

2014 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-823-9

Library of Congress Control Number 2014908647

Printed in the United States of America

To our wives, Amanda and Ginny, and our childrenwithout whom we would know precious little of the Shire .

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: In a Hole in the Ground There Lived an

Enemy of Big Government

FOREWORD

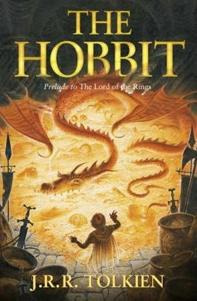

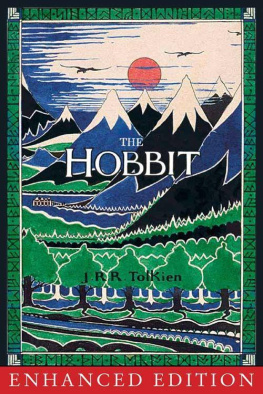

Jonathan Witt and Jay Richards were fortunate men. They read Tolkien while they were still boys. I did not encounter Tolkien until I was into my sixties. No doubt, the reading of Tolkien at any adult age makes you young again. But it also makes you wonder if you are wise, with the kind of wisdom we find in Bilbo, Frodo, Sam, Gandalf, and the forces of good that populate Gondor and the Shire. The tales of Tolkien assure us that our desire to live happily ever after is not wholly in vain. Yet, no books bring home the sense of loss and doom that we often experience in our souls more vividly than The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings . Witt and Richards seem to have caught the spirit that animates this most famous of the second creations that we contemplate in our literature.

As the twenty-first century rolls on, we find that we have the original tales of Tolkien, including his unfinished ones. We also have myriads of commentators who have undertaken, as they suppose, the delicate task of clarifying for us what Tolkien was really about. We have, in other words, a literature about literature. It goes without saying that no one reads Tolkien without gaining some insight into himself, the cosmos, and God. And yet, many interpretations of Tolkiens work did miss the mark, often widely. Witt and Richards deftly take us through these efforts that too often explain Tolkien by explaining him away. This is why it helps to have wondered about Tolkien since one was a boy. The recalled magic enables us to see through the explanations that, in effect, miss what Tolkien was about.

The title and subtitle of this book deserve comment. The Hobbit Party might refer to a movement, even a political party. The distributists, the ecologists, the hippies, even the Marxists and the atheists, as well as the Catholics and other such believers and reasoners, have all claimed Tolkien for their own. The stories we read in Tolkien are nothing if they are not about journeys and marches. Yet, the stories are ultimately about home and staying at home, about the hope that we never have to leave our homes once we have discovered where we are finally intended to dwell.

But our homes and families are under siege in this world, often by politicians and political parties we ourselves support. As this book suggests, we are more threatened with soft democratic tyrannies than with the blatantly bad ones. At first sight, we seem to suffer from our own greed or lethargy. We do not want to take the trouble to acknowledge who is for us and who is against us. Reading Tolkien makes us more vividly aware of the scriptural admonition that our struggles are not just about flesh and blood but about principalities and powers (see Eph 6:12). The father of lies is right at home in a world in which we lie to ourselves about what is so that we can proceed to do what we want.

But a party can also mean a gathering together of friends and family to rejoice in what is worth celebrating. At celebrations and parties, we give gifts and receive them. Why do we do this? It is not because we are bent on supplying to others what they do not have. The economics of the Shire makes it clear that the things we need we should make and acquire for and from others by fair exchange. If large markets make it possible to feed, clothe, and house many others, well and good. We were intended to discover what works and put aside what does not.

But something beyond necessity hovers over the tales of Tolkien. The important things are not really necessities. Indeed, we ourselves need not exist. The best things are given to us. It is a sign of character to be able to accept gifts from others, including from God himself. The Mordors of this world are places where all gifts cease. The eye that sees everything allows no privacy. It allows no place wherein we can be ourselves. The Hobbit Party by contrast is a scene of joy and abundance, of the time when all else is done, a time for listening to tales that explain who we are.

That there is evil in the world cannot be denied by most sensible men. It is the truth that hovers over all mankind. It provokes us. Each of us must take our stand. It is on this stand that we will be judged. We find ourselves living our lives in a divine plan that we, like Bilbo and Frodo, would just as soon avoid. We think that because we are among the insignificant of this world it will pass us by. None of our deeds, we think, can be great, because we are so small. Tolkien tells a different tale. The divine plan follows not just the paths of universal history and the great heroes of this world, but the detours of Nazareth, Tarsus, and Tagaste, where Augustine, in his teens, read Cicero. Seemingly insignificant places are often where the real events that define our essential being took place.

But the great battles of history are not insignificant either. It is not an evil to resist evil. Tolkien, as we read in these sober pages, was not a pacifist, nor did he glorify war. But he fought in the trenches of World War I; he knew the horror of war. He also knew what happens when we lose a war. The good side does not always win. And we can choose not to fight against an enemy who does not understand what man is. So, as Witt and Richards remark, Tolkien did understand a freedom that, once given to us, also requires our choosing to understand and defend it.

Evil is indeed the lack of a good, but it is also the lack of a good that should exist in a free being, angelic or human. Once a free being chooses himself over the order of things, he works to corrupt what is good in others. The Hobbit Party could not be what it was unless what we understood, chose, and yes, if need be, fought for made some ultimate difference.

We tend to forget that our freedom is itself a result of the divine creation that made us what we are. God did not want a world in which nothing that any one did made a difference. Personal freedom makes those who possess it unique and different. They are what they choose. But their choices are not simply left alone, unnoticed or unresponded to by the divine freedom that brings all things to the good if it can. The one thing that it cannot do, and this awareness dogs the journeys of the characters in The Lord of the Rings , is to deny the freedom of those who choose to reject God. They are allowed their choices. And they, in defending their self-chosen world, seek to draw everyone else within it.

If the drama of our lives did not really have something at stake, the very possibility of a happy ending, the whole meaning of existence would evaporate. What this book is really about is the worlds that we choose in response to the divine gifts of reason and will. Such a world contains tragedy and suffering, even of the innocent. But it remains rooted in joy, that final result of choosing what is good, even if we have to suffer for our choice. The second creation that Tolkien offers us illuminates the first creation in which we exist. It is in the first creation that we are initially created. Through our choices, we respond to the gifts of life and reason. Eternal life, the only life that lasts, is the Hobbit Party for which we exist, with its joys.

Next page