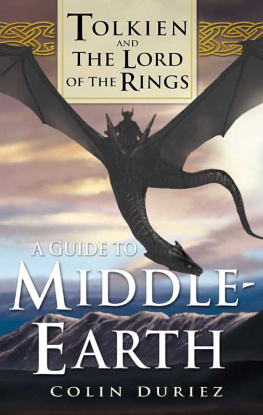

Copyright 1971, 1978 by Robert Foster

Interior art copyright 1975 by Greg and Tim Hildebrandt

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Del Rey, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

D EL R EY and the C IRCLE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Originally published in a limited-edition hardcover in the United States as A Guide to Middle-earth by Mirage Press in 1971.

A revised and updated edition was published in the United States in hardcover as The Complete Guide to Middle-earth by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, in 1978.

Portions of this book have appeared in different form as follows:

Niekas 16 (June 30, 1966), 1966 by Ed Meskys; Niekas 17 (November 1966), Niekas 18 (Spring 1967), Niekas 19 (1968), 1966, 1967, 1968 by Niekas Publications; Niekas 20 (Fall 1968) 1968 by Ed Meskys; Niekas 21 1969 by Ed Meskys.

ISBN9780345449764

Ebook ISBN9780593594490

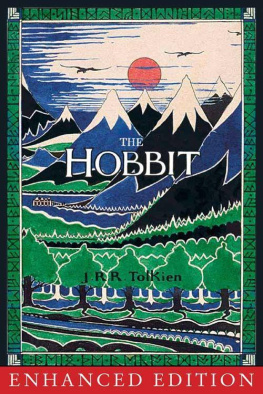

Cover design: Brock Book Design Co.

Cover illustration: Ted Nasmith

randomhousebooks.com

a_prh_6.0_141009069_c0_r0

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

W ith the appearance of The Silmarillion , the publication of J. R. R. Tolkiens mythopoesis is virtually complete. The reader can now appreciate the full scope and significance of the history of Aman and Middle-earth, the central stages in the great drama of the Creation of E. One can trace in detail the Light of Aman from the Two Trees on Ezellohar to the renewing power of the Phial of Galadriel in the stinking darkness of Shelobs Lair. The terror felt there by Sam Gamgee is better understood after reading of the Unlight of Ungoliant, and Boromirs desire for the Ring can be seen as a wisp of the Shadow of Melkor, who lusted after Light but created only Darkness. Not only do the great conflicts between East and Westfrom the First War and the Battle of the Powers to the Battle of Fornost and the War of the Ringreveal the nature of good and evil and the immeasurable compassion of Ilvatar, but also, the identity of the forces that intervene to give victory to the good suggests the progressive freeing of Man from the influence of both Valar and demons to work out his own destiny, known to Ilvatar alone.

Writing this revised edition of my Guide to Middle-earth has enhanced my awareness of these correspondences, designs which are surely central to the joy of Faerie and which give Professor Tolkiens work its marvelous and profound coherence. But it has also made me aware of the difference between the conception and the realization of this cycle of myth and romance, between the visionary scene and its frame, not yet ready to fix it in the Text. Yet these inconsistencies, which can bulk large in an alphabetic treatment of Faerie, should not be allowed to detract from the general bloom of this lushly foliated Tree.

So this revised Guide is limited to the Text, to published works by Professor Tolkien in the latest editions available to American readers. The basic text for The Lord of the Rings is again the Ballantine paperback edition, with emendations from the revised Houghton Mifflin hardback edition; Appendix C contains a concordance between the two editions. British editions contain several further emendations, which I have not taken into account; of those I have heard of or seen, the most significant is the change of d to dh in Galadrim and Caras Galadon , which resolves the confusion (encouraged, it seems, by the Elves themselves, as Christopher Tolkiens comment in The Silmarillion on Galadhriel suggests) between Sindarin galad light and galadh tree. The three exceptions to this rule of Text are sources which seem particularly trustworthy: the Pauline Baynes map of Middle-earth displays a number of place-names evidently given her by Professor Tolkien; Clyde Kilbys intimate Tolkien and the Silmarillion contains intriguing hints of the End; so much of the information contained in Professor Tolkiens letters to and conversations with my friend Dick Plotz has been corroborated by The Silmarillion that I feel confident in using other items.

In general, I hope that I have not forgotten the limits of a reference work. I count myself fortunate to have wandered in the Fairy-realm of Arda for fifteen years now, and while my tongue is certainly not tied, for the sake of my own delight I have learned not to ask too many questions, lest the gates should be shut and the keys be lost. This Guide is intended to be supplementary to the works of Professor Tolkien and no more; its value is that it can clarify deep-hidden historical facts and draw together scraps of information whose relation is easily overlooked, thus aiding the wanderer in Arda in his quest for its particular Truth. When matters are unclear in the Text I have tried to remain silent, but those places where I have been unable to restrain my conjectures are liberally sprinkled with perhaps, presumably, and such words. By now the entries which comprise this Guide represent the product of ten years of intermittent labor and frequent correction by myself and careful readers, until I can hope that the errors which remain are more mechanical than substantive.

There is one major deviation from this conservative treatment of the Text. Unlike The Lord of the Rings , whose Appendix B provides precise dates for the events of the Second and Third Ages, The Silmarillion contains little exact chronological information aside from sporadic indications of the passage of years (But when Tuor had lived thus in solitude as an outlaw for four years) and rough dating from the first rising of the Sun. Desiring to make the information concerning the First Age more compatible with that for later Ages, I have taken it upon myself to coordinate these indications of time into a Chronology of the First Age (Appendix A). This Chronology may help to unify in the minds of readers the episodic sequence of events and personages in the Wars of Beleriand; by counting years, it also underscores the rapid collapse of Beleriand after Dagor Bragollach and the tragedies of the early deaths of Huor (at 31), Trin and Nienor (36 and 27), and Dior (about 39). In addition, I must confess to having succumbed to the scholarly joys of writing an Appendix. The dates given for the First Age, therefore, both in the entries and in Appendix A, are strictly my own and should be taken as approximations rather than as completely trustworthy deductions; my derivation of these dates is fully explained in the Appendix.

The principles involved in determining entries are fairly simple. In general, any capitalized word or phrase receives a separate entry unless it is a clearly identified epithet or a translation of a name not used independently of the main name; thus there is an entry for Slimo but not for its full translation, Lord of the Breath of Arda , and Voronw as the epithet of Steward Mardil is not listed separately. In addition, certain noncapitalized items (mostly the names of species and objects, such as the great spiders and ithildin) have been included. Variant spellings (which in most cases reflect Professor Tolkiens further development of the Eldarin languages) are noted, but most variations in the use of accent marks have been ignored. Page references in main entries are to significant references only; cross-references usually cite the first occurrence only. Geographical entries do not always cite the maps on which the place in question is shown, and historical entries occasionally use dates given in Appendix B without citation; in both cases the references can easily be found. References to the various Indices are given only when they contain new information.

When entries are genuine forms in Middle-earth languages, I have indicated this, giving translations wherever I am sure of them. A question mark following a language identification or translation obviously indicates uncertainty. Translated Rohirric (Old English) forms are occasionally translated again into modern English; the language of other forms is indicated as tr. wherever I felt there was a possibility of confusing them with Elvish or genuine Mannish forms. However, by and large I have not indicated the language of names and terms Anglicized into English, Germanic, or Celtic equivalents; as Appendix F of The Return of the King suggests, most Adnaic, Rohirric, Westron, Mannish, and Hobbitish forms have been so translated. In The Lord of the Rings I have assumed that English versions of Middle-earth names (e.g., Treebeard for Fangorn ) represent Westron forms used by Men and Hobbits. But in The Silmarillion this is obviously not the case, since Westron did not develop until the late Second Age. Here I have assumed that the English versions, even though capitalized, are merely translations intended for the convenience of the reader, not translated Mannish names.

Next page