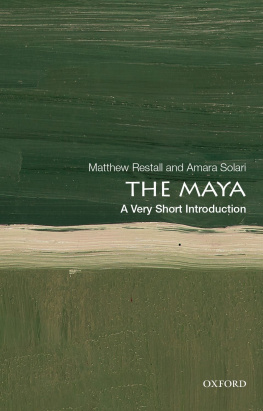

About the Authors

Matthew Restall and Amara Solari are specialists in Maya culture and colonial Mexican history. Between them they have over thirty years of experience studying Mayan languages and researching the Maya past in the towns and archives of Mexico, Central America, and Spain. Their knowledge of Yucatec Maya gives them the rare ability to decipher the original Maya texts. Both teach at the Pennsylvania State University. Restall is Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Latin American History and Anthropology and has published over a dozen books, including Maya Conquistador and Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Solari is assistant professor of art history and anthropology, has published articles on colonial Maya mapping systems, and has written a book on Itzmal, Yucatan.

1

The History of the End of the World

The Maya Prediction

This is the history of the end of the world... the flood shall take place for the second time; this is the destruction of the world; this then is its end.

from the colonial-period Yucatec Maya Book

of the Jaguar Prophet (Book of Chilam Balam)

Predicted by the Mayans. Confirmed by science. Never before in history has a date been so significant to so many cultures, so many religions, scientists, and governments.

from the promotional material for Sony

Pictures 2012

At a remote point along the road that runs between two large towns in the Mexican state of Tabasco, a large concrete factory was built. The site was chosen for its access to stone and its location beside a highway. As far as anyone knew, or cared, nothing important lay thereno homes or valuable land. In the course of the factorys construction in the 1960s, a few man-made hills were bulldozed. By chance, several carved stone tablets were spotted among the rubble. They were saved, passed along to local officials, and eventually deposited in a Mexican museum as curiosities. The hieroglyphs could not be read, and nobody could therefore be sure how old or how significant the stones might be.

In fact, the factory had been built upon an ancient Maya city, which was completely destroyed by the construction. Known to archaeologists today as El Tortuguero, the city was one of the most important smaller Maya sites in the region, subject toand tied dynastically through its rulersto the impressive city of Palenque (in todays neighboring state of Chiapas). The heyday of El Tortuguero seems to have been the seventh century; most of the carved monuments rescued from the site date from the reign of King Jaguar (Balam Ahau, AD 644679).

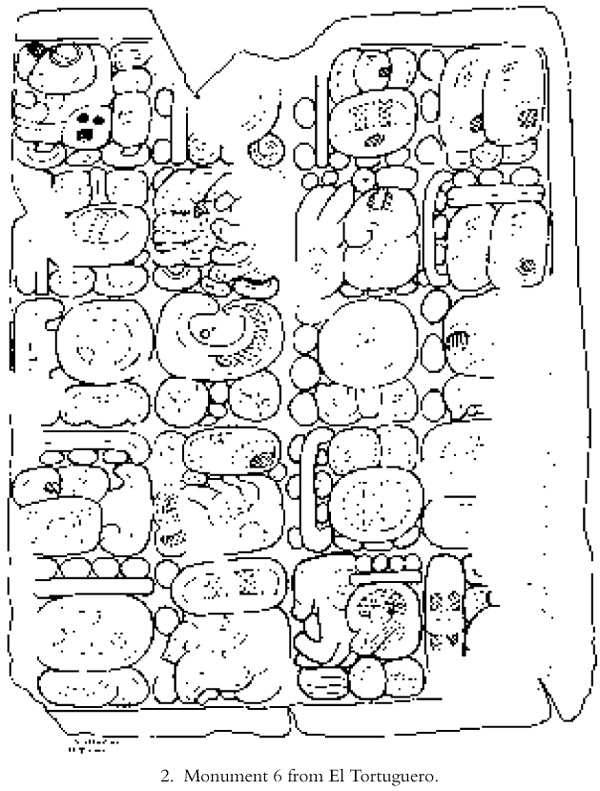

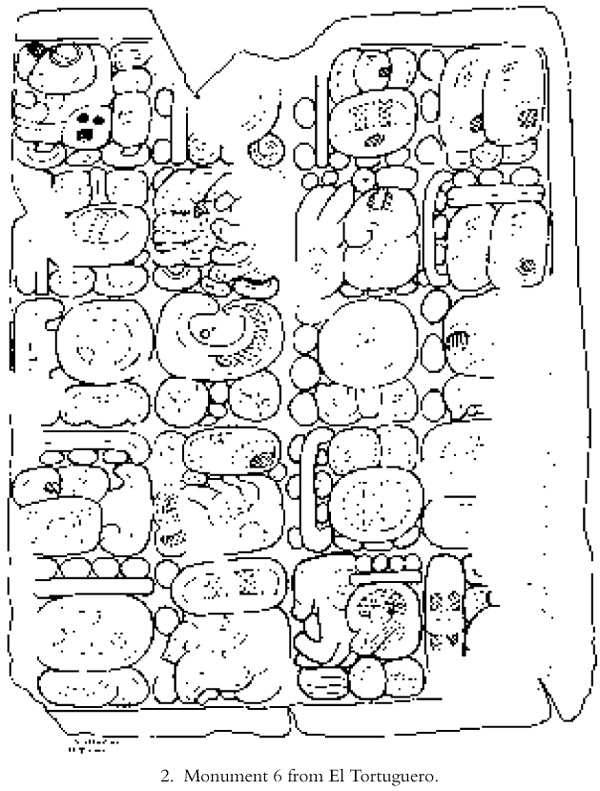

The rescued monuments gathered dust for decades, until advances in Maya epigraphy (the decipherment of glyphs) inspired scholars to take a look at the long-forgotten, fragmented texts on the El Tortuguero stones. One of them was dubbed Monument 6 by Mayanists (Mayaniststhe large international community of professional and amateur scholars who study the Maya, especially the ancient Maya, rather than their present-day descendentsgive cities, buildings, and monuments names and numbers that tend to stick, even when the real names are later translated). Monument 6 had been broken up and its fragments scatteredfour in a local Mexican museum, one in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, two in private collections, several other pieces lost. But when reconstructed, the glyphic text told not only the history of the king who had commissioned the monument; it seemed also to have calendrical significance.

Despite the damage and scattering and the loss of portions presumably destroyed by construction in the 1960s (if not before), Monument 6s glyphs are legible (drawn in figure 2). There are various ways to transcribe alphabetically and translate such a text; that caveat aside, the text can be read as: Tzuh tzahoom uyuxlahuun pikta / Chan ahau ux unii / Uhtooma ili / Yeni yen bolon yookte kuh / Ta chak hohoyha. The literal meaning of this might be: The thirteenth one will end on 4 Ahau, the third of Uniiw. There will occur blackness and the descent of the Bolon Yookte god to the red. Alternatively, the second line might read: There will occur a seeing, the display of the god Bolon Yookte in a great investiture. A more idiomatic translation would read something like this: The thirteenth calendrical cycle will end on the day 4 Ahau, the third of Uniiw, when there will occur blackness (or a spectacle) and the God of the Nine will come down to the red (or be displayed in a great investiture).

The meaning is hardly clear, but with the application of some imagination the text can become an ominous warning, perhaps even an apocalyptic one. It has certainly become one of the sparksby some accounts, the sparkthat ignited the firestorm of the 2012 phenomenon. The Tortuguero text has been cited over and over since 1996 (when epigraphers Stephen Houston and David Stuart first published a translation of it) as the earliest example of Maya predictions of the worlds end. This is partly because scholars initially speculated that the text might be a rare case of Classic Maya prophecy; subsequent retractions (to which we shall turn in the next chapter) fell on deaf ears. It is also partly because the passages enigmatic and incomplete nature invites speculation: if we choose the first translation variant, black and red, the colors of darkness and blood, seem portentous; who is this god called Bolon Yookte, or the nine Yookte gods, or the Gods of the Nine, and what catastrophe might his or their descent to Earth herald?

Above all, the Tortuguero passage has sparked controversy because the date to which it refers is approaching soon; in our calendar it is December 21, 2012 (sometimes given as 10 or 23, but usually 21, the winter solstice). In the Maya calendar, the date is a series of glyphs representing numbers; written out using our numbers, that date is 13.0.0.0.0. The zeros seem ominous, and the cycle whose end it marks is an impressively long one5,126 years (more specifically 1,872,000 days or 5,126.37 years). That span of time takes us back to the dawn of human civilizationthe beginnings of dynastic Egypt, the rise of Minoan civilization, the inception of Stonehenge, and perhaps too the dawn of the Maya world. Had the Maya calculated that settled human life existed within a specific time frame, a kind of cosmic, civilizational clock? And if so, is the tick of that clock getting louder and louder? Is the alarm about to go off ?

It is tempting to comb through Maya literature to find clues as to what the Maya thought would happen on the day 13.0.0.0.0, and indeed many have succumbed to that temptation. Before we turn to look at some of those cluesin Maya carvings, ancient glyphs, and colonial-period alphabetic textsa brief explanation of four core aspects of Maya civilization is necessary. These are political organization in the Maya region; the nature of Maya religion; the structure of the calendar; and creation mythology.

The Maya area was never politically unified. The peoples that we call the Maya comprised a civilization; they all shared a discrete set of cultural traits. But although they spoke dialects of the same family (the Mayan language family), all the Maya never spoke the same language. Nor did they ever recognize a common sense of identity or answer to a single ruler or dynasty. The region, stretching today from southern Mexico across Guatemala and Belize into Honduras, contained hundreds of polities (see figure 3). For thousands of years leading up to the Spanish invasion that began in the 1520s, small Maya kingdoms vied for regional control. Some built spectacular cities and conquered their neighbors. But no kingdom was able to dominate the whole Maya area, let alone any of its most populated and prosperous regionssuch as northern Yucatan or highland Guatemala.