To Charles .

H.T.

This book is dedicated to all the miracles through Bill W. and Dr. Bob.

They are good medicine.

P.B.

T HE SPANISH WORD milagro is usually translated as miracle. We live today in a world that seems short of miracles, a world where the miracles that do happen go unremarked. Based on traditional Mexican talismans, the tiny, personal charms known as milagros remind us that miracles can be small, they can be numerous, and they can happen every day. Often intensely personal, milagros are individual and universal, and they offer a way to close the gap between the spiritual and the commonplace.

As charming folk art, milagros are talismans against illness, trouble, and pain. But they are more than just a quaint remedy for problems. They are symbolic of a covenant between a believer and a higher spirit, tangible testimony that a promise has been fulfilleda marriage has been saved, an ailing parent has been restored to good health, a love has been found. Whether you look at their place in your life as a symbol that you are trying something new or as a means to focus yourself on a transition, milagros offer an alternative approach to spirituality.

From the earliest of times, humankind has wanted to communicate with a higher power. We have been giving thanks and propitiation in the form of offerings to gods for thousands of years. The early Sumerians, Persians, Minoans, and Egyptians gave votive gifts depicting animals and people, and evidence of milagros as an ancient custom exists throughout Europefrom Greece, where offerings were given to Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing, north and west into what is now Ireland and Scandinavia. Charms have been offered by such illustrious historical figures as Anne of Austria, who showed her gratitude for giving birth to an heir to the French throne with a small, winged, silver representation of the infant; and Hernn Corts conqueror of Mexico, who is believed to have presented a gold scorpion emblazoned with emeralds, rubies, and pearls at the shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe to show his indebtedness for having been saved from a scorpion bite.

Adopted into the rituals of Christianity as a way to thank the saints for answered prayers, the pagan tradition of milagros found its way to the Americas with the Catholic conquistadores. Because the invaders destroyed holy sites throughout the Americas and punished the indigenous peoples for practicing their religion, many traditions of worship have been lost. However, the newly Christianized people of these places took up milagros and their use has continued to endure. Where parts of Guatemala were plagued long ago by pest infestations, grasshopper milagros have been discovered; and the Inca were most likely placing their faith in the fertility of the ground when they planted gold effigies of maize leaves and cobs during sowing festivals. Offerings have been found in as far-flung places as the sacred mounds of Peru, the pyramids of Mexico, the ancient kivas of the American Southwest, and the sacred pools in the Yucatan peninsula.

In Latin America and in areas of the United States where there is a large Hispanic population, offerings are even today a common sight. The little silvery milagros are often found piled in bowls, affixed to crosses with tiny silver nails, or placed at a church altar or a makeshift household shrine. Milagros come in an endlessly imaginative variety of shapes, sizes, and materials. Sometimes quite sumptuousbejeweled, elaborately carved, or finely wrought from precious metalsthey can be humble, too. Quality has no correlation to sincerity or to outcome. Your milagros are reminders that any act of devotion, no matter how small, is worthy.

That milagros still hold power to affect our troubles testifies to the endurance of a belief system that has eluded repression and destruction to survive for centuries. Perhaps the very modesty of milagrosor their folksy and unassuming status in a complex religious systemhas enabled these unsophisticated representations to endure in a modern world wildly and unimaginably different from that which they originated in. Their unthreatening, even whimsical, charm may also account for their increasing popularity in the United States. Engulfed in a mass pop culture and sated with consumer goods, we may look at milagros as a way to connect to the durable belief systems of ancient cultures.

The most widely used shapes for milagros are those that represent body parts such as feet, heart, hand, head, and lungsall those nooks and crannies of the body where ailments settle in and stay. The contemporary interpretation of milagros youll find in this book (utilizing popular anatomic shapes) is an introduction to the ways and the wisdom of an age-old culture. May learning about these small miracles enhance your life forever.

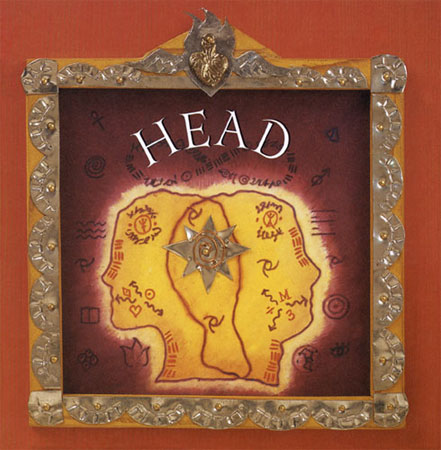

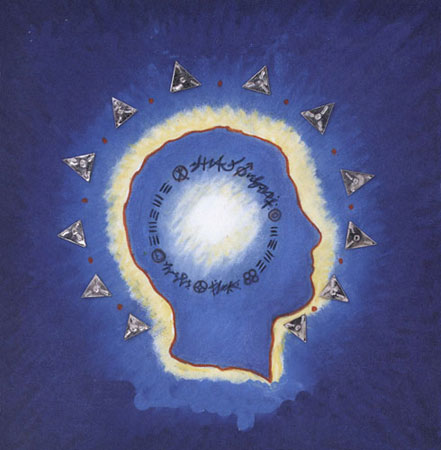

HEAD

KNOWING IS WISDOM

Y OUR HEAD IS your own personal fountain of wisdom. You use it to think and to reason, to plan and to dream.

Head milagros have as much variation as heads do in real life, and represent all ages, shapes, and sizes. Male milagro heads might have beards or mustaches, lots of hair, or be balding. Milagros of female heads can have distinctive, elaborate hairdos, and some even have earrings. They can be shown in profile, full face, or even in a three-dimensional form.

A photograph can serve as a contemporary version of the head milagro: It is not uncommon to see snapshots of happy infants or smiling husbands and wives placed on statues of favorite saints as a show of gratitude. Sometimes the photo represents the person before calamity struck: a reminder of the state to which the stricken person hopes to return.

El dolor es real cuando usted piensa gue lo es.

Pain is real when you think it is.

O UR HEADS ARE where our thought processes begin, where we register our pain, and where we consider the sometimes difficult task of asking for help to alleviate the pain. Head milagros are traditionally offered for real painheadaches, memory loss, difficulty learning, and injury or trauma. But they are also offered for more ineffable problems, such as mental illness.