Contents

Editor

Greg Payne

Origination

Christine Jennett

Published by

Greenlight Publishing

The Publishing House, 119 Newland Street

Witham, Essex CM8 1WF

Tel: 01376 521900 Fax: 01376 521901

www.greenlightpublishing.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 897738 184 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 897738 450 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 897738 467 (Mobi)

eBook conversion by Vivlia Limited.

2012 Julian Evan-Hart & Dave Stuckey

All rights reserved. No part of this publication, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Greenlight Publishing.

Author Profiles

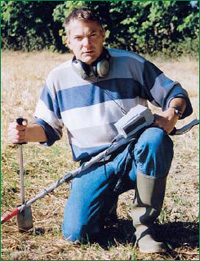

Julian Evan-Hart

I was born in 1962 at Welwyn Garden City. My family then moved to the small village of Weston, also in Hertfordshire. It was here that my passion for history, wildlife and the collecting of all things interesting started.

From a young age collecting was my pastime, and items such as pottery fragments from the local Roman villa, fossils, and other curiosities all found their way into my museum. At the tender age of six I found a mammoth tooth lying in the recently excavated soil from some road works, to add to my ever-growing collection.

While attending St Georges School in Harpenden in the mid-1970s I heard for the first time of a gadget called a metal detector. Despite being intrigued by these devices it was not until the late 1980s that I would actually be able to purchase such a machine.

I found that other people in and around Stevenage where I now live shared my passion for metal detecting. Therefore a natural progression was to get together and form a group. This achieved, we call ourselves The Pastfinders.

To say that I am interested in metal detecting is definitely an understatement: for me its a passion. It seems that I am always researching for Roman villas or to find the spot where a Second World War aeroplane crashed. Metal detecting has enriched my life more than any other of my past hobbies.

Dave Stuckey

B orn in Hannover, West Germany, in 1956, I then spent most of my childhood travelling the world as part of a service family. My formative years were spent in such places as Malaya and Singapore. After finishing school in Gutersloh, again in West Germany, I then joined the Royal Navy as a Seaman Gunner in 1973. It was during my years in the RN that I became interested in the hobby of metal detecting, after seeing people with these rather curious devices pacing up and down the beaches of Southsea, near Portsmouth.

I went up to one of these guys and asked him what he was looking for. He promptly pulled out a neck chain that held dozens of gold rings, all of which he had found on that particular beach! I was so impressed that I decided to get one of these machines for myself.

I ordered my first detector, a C-Scope IB300, from Joan Allens in 1976 and havent looked back since.

After teaming up with Julian Evan-Hart in the mid-1990s, we formed a group known as The Pastfinders, which now has many members.

Since taking up metal detecting, I have developed an enormous fascination for history and have even taken part in archaeological excavations in my own locality. I have also built up a good relationship with the Archaeological Department of Hertfordshire County Council, with whom I liaise regularly.

Introduction

D id you find the subject of history tediously uninteresting when you were at school? Were you bored to tears when being made to learn about our past from chalkboards, dry old textbooks, and more recently Videos and DVDs? If you were, then you certainly werent alone.

Perhaps, on the other hand, those visits to museums ignited some spark of interest in our past but left you feeling somewhat frustrated? You felt an overwhelming desire to touch the artefacts and coins that were once the everyday items of use by our ancestors, but those glass barriers denied you the privilege of making that physical contact with the past. Again, you certainly werent alone.

Until about three decades ago that privilege was reserved for the lucky few such as archaeologists, museum staff, historians, and scholars.

Archaeologists, of course, would normally have been the first to touch any object that came out of the ground after having been lost or deliberately hidden for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. These finds would then have been forwarded to museums, which had the task of cleaning and conserving the artefacts prior to them being studied by experts and scholars. Only then would a select few of these treasures be put on display for the public to admire.

Towards the end of the 1960s, however, new technology appeared that would change that system and grant the privilege of handling old or ancient finds to the mainstream public. The hobby of metal detecting had been born.

Early metal detectors were quite rudimentary. Their basic design gave them the appearance of a simple transistor radio attached to a stick with a small coil on the end.

By the 1970s, however, metal detector technology had improved dramatically. The machines that began appearing on the market were vastly superior to their rather basic predecessors, and this was reflected in the number of amazing discoveries that were being made. The Water Newton Hoard and the Thetford Hoard are just two examples of some of the fabulous treasures that came to light in those early years.

Enthusiasm for the hobby grew and it became an increasingly popular pastime. Visitors to the coast soon became accustomed to the strange characters that could be seen pacing up and down the beach swinging their electronic wands in search of lost valuables.

Early treasure hunters who werent fortunate enough to live near the coast were hardly disadvantaged, however. They were soon to discover that the countryside around them had an even greater potential. Britain had literally millions of acres of virgin farmland that had never been detected on previously. Excitement grew over the staggering number of amazing finds that were being made by the early pioneers of metal detecting. Museum cabinets soon began to fill as more and more treasures came to light.

Many began to see the hobbys potential as increasing numbers of new archaeological sites were discovered. In addition, the discovery of many previously unrecorded types of coins and artefacts improved our knowledge of Britains past. However, there were some people who were rather less than enthusiastic about this new pastime.

Many within the archaeological community regarded metal detectorists as a threat to the nations heritage rather than a huge potential benefit. Campaigns were launched in order to have severe restrictions imposed on the use of metal detectors; some even wanted the hobby banned altogether.

Fortunately, the rights of the general public to go exploring the countryside with metal detectors were upheld. Ancient Treasure Trove laws and Codes of Conduct were emphasised to all users of metal detectors and were accepted as a fair compromise.

Although some hardliners still exist within the archaeological community, the attitudes of many have softened in recent years. The realisation that co-operation could bring far greater benefits than confrontation has, in many cases, resulted in good working relationships in many parts of the country.