Acknowledgements

I would like to thank and acknowledge all the help I have been given over the last two years. Two people especially have helped enormously with this book. The first is Tony whose idea this book was and his input, particularly into the finds chapter which was enormous, as was his help with the overall style throughout the book.

The second is Micky who must also be mentioned. Her sketches, illustrations and line drawings of finds are first class and provide the informal and amusing flair that I was looking for. Also for her input into the proof reading -she managed to correct my writing into readable English!

There are a few others like Sam at the British Museum; Nigel and Gordon from our club who read the proofs, and corrected any slip-ups. Any mistakes that are still there are mine completely. If you find any, please feel free to let us know so we can correct them on the first reprint.

I would also like to acknowledge and thank the following photographers for the use of their photographs.

- The Trustees of the British Museum and the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS).

- Mike Hogan, who provided one of the photos of the Frome coins, and the one of Dr. Alice Roberts and me.

- Steve Minnitt, the director of Somerset Museum service who kindly provided the Frome hoard display layout in the Taunton Museum.

- Neil, a Somerset farmer, who provided a photo of himself and his cows.

Dave Crisp 2012

Editor

Greg Payne

Design Editor & Origination

Christine Jennett

Published by

Greenlight Publishing

The Publishing House, 119 Newland Street,

Witham, Essex CM8 1WF

Tel: 01376 521900

www.greenlightpublishing.co.uk

ISBN 978 1 897738 47 4 (Print)

ISBN 978 1 897738 48 1 (ePub)

ISBN 978 1 897738 4 9 8 (Mobi)

eBook conversion by Vivlia Limited.

2012 Dave Crisp

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Greenlight Publishing.

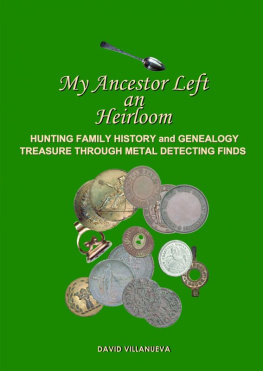

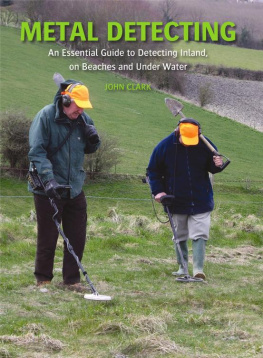

Introduction

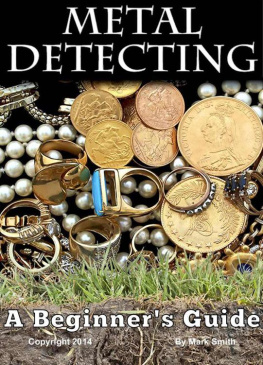

M y detecting partner Tony and I both started from scratch with no knowledge of metal detecting whatsoever. But between us we now have over 25 years of experience.

It was in July 2010, after I had found the Frome Hoard of Roman coins, that Tony realised that there was limited information (in terms of books) for newcomers to the hobby to buy that would tell them what they needed to know. So he put it to me that we could put together an essential book on metal detecting, with all the relevant information, including the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and the1996 Treasure Act. This would also give me an opportunity to tell my story as finder of the Frome Hoard.

Dave Crisp

We are sure that you will find in this book the knowledge that you need to start the hobby correctly. Also covered is where to go, and how to use your detector. You will also see a selection of finds to help on initial identification of the objects you recover. There is a section on the 1996 Treasure Act and the Portable Antiquities Scheme where, through your local Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs), you can get help with the identification of finds. We have tried to make this a light-hearted look at our hobby and how to go about it, but with a look at the serious side of doing things correctly.

Throughout this book we have tried to emphasise the benefits of cooperation between museums, the archaeologists involved in the Portable Antiquities Scheme and detectorists.

We have also been very lucky to have comments and contributions from academics such as Roger Bland (head of PAS at the British Museum); Steve Minnet (Head of Somersets Museum Service), and Katie Hinds (the FLO for Wiltshire). We are also indebted to Pippa Pearce for help on the conservation of finds, and Sam Moor-head (Iron Age and Roman Finds Advisor at the British Museum). Good luck and good detecting - Dave Crisp

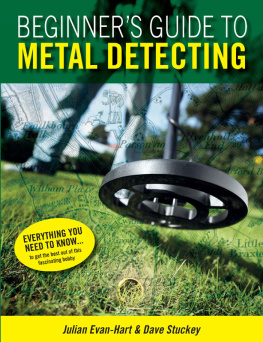

Brief History of Metal Detectors and Our Hobby

What is a Metal Detector?

A metal detector emits an electromagnetic field from its search coil. When a metal object enters this field it causes a change or distortion. This is relayed to the control box, which analyses the response and provides a sound in the operators headphones and, on some models, a display on a screen. The strength and type of the signal can also tell the detector how deep the item is, and the type of metal it is made from. This information can also be displayed on some detectors.

Second World War, 1942, mine detector.

One of the first detectors was built by an engineer by the name of Gerhard Fisher. In the late 1920s he was working on radio direction finding equipment for aircraft and found that metal ore in the ground, or metal roofs on buildings, affected the system. From this early beginning he designed a metal detector, for which he received a patent in 1937. These very early machines were also used by geologists, gas and electricity companies, and the police. During the Second World War and afterwards they also helped to clear enemy mine fields. These early mine detectors were heavy and used a lot of power, but they were the cutting edge of technology at the time.

Lt. Jozef Kozacki designed the first practical electronic mine detector, called the Mine Detector Polish Mark 1. It was soon improved upon and mass produced. Some 500 were issued to the British Army in time for use prior to the Battle of El Alamein in October 1942. An example is shown here (reproduced with permission). It looks quite familiar to a 21st century detectorist!

After the war these very early machines were used at the very start of our hobby, although in those days you needed a partner just to carry the battery pack! It was in the 1950s and 1960s, with the invention of the transistor, that detectors transformed into lighter machines which used batteries that could be fitted integrally. In America, Charles Garrett obtained a patent for a Beat Frequency Oscillator type metal detector and this is when the hobby really started up, with more and more manufacturers coming into the market. Garrett was joined in the 1960s by other now well-known names such as Whites and Fisher.

Shown above right is the first detector I ever purchased in the late 1960s. As you can see, its just a hoop on a stick with an adapted transistor radio; but it still works (after a fashion!). It is tuned by using the slider on the main stem. I was assured, by the shop assistant that I would find lots of things with it! After a couple of outings in the garden it went into the cupboard, and has seen many more cupboards since then. I now bring it out as a curiosity when giving talks!

My first BFO metal detector from the late 1960s.

Tesoro, who started in the late 70s, became one of the early makers of a full range of machines. One of these models was the legendary, Silver Sabre, renowned for its ability to find small hammered coins. Tesoro, which is Spanish for treasure, are still going and I still use my Laser B1 as a backup machine.

Great strides at that time were also being made in improving coil design, important for depth and signal recognition. Induction Balance machines gave the opportunity to discriminate between metals and ignore the targets you did not want (iron). So with the ability to read the type of metal found, machines were getting more sophisticated. Also, with further improvements in discrimination, they were going forward in leaps and bounds.