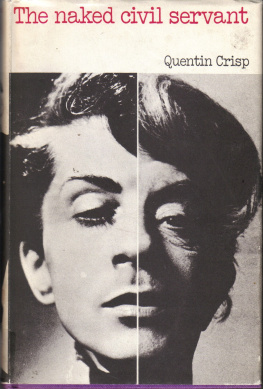

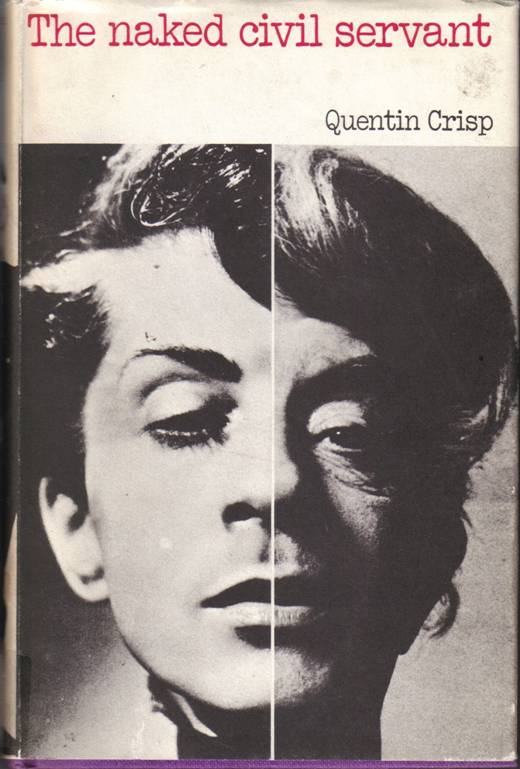

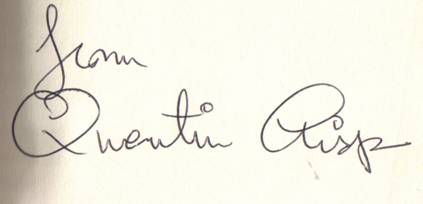

Quentin Crisp

THE NAKED CIVIL SERVANT

First published by Jonathan Cape Ltd 1968

From the dawn of my history I was so disfigured by the characteristics of a certain kind of homosexual person that, when I grew up, I realized that I could not ignore my predicament. The way in which I chose to deal with it would now be called existentialist. Perhaps Jean-Paul Sartre would be kind enough to say that I exercised the last vestiges of my free will by swimming with the tidebut faster. In the time of which I am writing I was merely thought of as brazening it out.

I became not merely a self-confessed homosexual but a self-evident one. That is to say I put my case not only before the people who knew me but also before strangers. This was not difficult to do. I wore make-up at a time when even on women eye-shadow was sinful. Many a young girl in those days had to leave home and go on the streets simply in order to wear nail varnish.

As soon as I put my uniform on, the rest of my life solidified round me like a plaster cast. From that moment on, my friends were anyone who could put up with the disgrace; my occupation, any job from which I was not given the sack; my playground, any caf or restaurant from which I was not barred or any street corner from which the police did not move me on. An additional restricting circumstance was that the year in which I first pointed my toes towards the outer world was 1931. The tidal wave, started by the fall of Wall Street, had by this time reached London. The sky was dark with millionaires throwing themselves out of windows.

So black was the way ahead that my progress consisted of long periods of inert despondency punctuated by spasmodic lurches forward towards any small chink of light that I thought I saw. In major issues I never had any choice and therefore the word 'regret' had in my life no application.

As the years went by, it did not get lighter but I became accustomed to the dark. Consequently I was able to move with a little more of that freedom which T. S. Eliot says is a different kind of pain from prison. These crippling disadvantages gave my life an interest that it would otherwise never have had. To survive at all was an adventure; to reach old age was a miracle. In one respect it was a blessing. In an expanding universe, time is on the side of the outcast. Those who once inhabited the suburbs of human contempt find that without changing their address they eventually live in the metropolis. In my case this took a very long time.

In the year 1908 one of the largest meteorites the world has ever known was hurled at the earth. It missed its mark. It hit Siberia. I was born in Sutton, in Surrey.

As soon as I stepped out of my mother's womb on to dry land, I realized that I had made a mistakethat I shouldn't have come, but the trouble with children is that they are not returnable. I felt that the invitation had really been intended for someone else. In this I was wrong. There had been no invitation at all either for me or for the brother born thirteen months earlier.

A brother and sister seven and eight years older than I were presumably expected though hardly, I imagine, welcome. Before any of us were born there were bailiffs in my parents' house in Carshalton.

When they moved to Sutton we by no means lived in poverty. We lived in debt. It looks better and keeping up with the Joneses was a full-time job with my mother and father. It was not until many years later when I lived alone that I realized how much cheaper it was to drag the Joneses down to my level.

As soon as I was a few days old I caught pneumonia. I was literally as well as metaphorically wrapped in cotton wool. From this ambience I still keenly feel my exile. When I was well again, I saw that my mother intended to reapportion her love and divide it equally among her four children. I flew into an ungovernable rage from which I have never fully recovered. A fair share of anything is starvation diet to an egomaniac. For the next twelve years I cried or was sick or had what my governesses politely called an 'accident'that is to say I wet myself or worse. After that time I had to think of some other way of drawing attention to myself, because I was sent to a prep school where such practices might not have seemed endearing.

In infancy I was seldom able to vary the means by which I kept a stranglehold on my mother's attention, but on one occasion I managed to have myself 'kidnapped'. Everybody in the family always used this word to describe the incident but there were no ransom notes. I did not at that time sit on the knees of golden-hearted gangsters while they played poker in rooms with the windows boarded up. The whole drama was in one act.

Our nurse told my brother and me that we were about to be taken for a lovely walk. I began as usual to deploy delaying tactics such as keeping my arms as rigid as a semaphore signaller's while she tried to put my coat on. Then as now I didn't hold with the outer world. Tired of these antics, nurse took my brother downstairs and they hid. Not knowing that they were doing this, my mother, when I asked her where they were, told me I might go just as far as the front gate to look for them. I went not only to the gate but out into the street and down to the corner of the Brighton Road. There I met a rag-and-bone man who offered me a lift in his hand-cart.

I was found on Sutton Downs two or three miles from home by one of my mother's friends. Only about two hours had passed, but the whole neighbourhood had been stirred up and my mother had telephoned the police. This was nice. Unfortunately the doctor who examined me on my return advised my mother never to question me about the incident. That was a pity, for now I can remember nothing of my journey.

For many years I was troubled by two half-formed memories. In one the ground is covered with crumpled newspapers. I put my hands on these and move them about but I never lift any of them up. Underneath is something unpleasant. To this day I have no idea whether this has something to do with my ride in the hand-cart or not. Perhaps one should regard the kidnapping as just the first instance of my being picked up by a strange man at a street corner.

The other memory was of drawing something longa thin tube, a piece of cordbetween my finger and thumb. I felt that there were lumps inside the tube. The sensation was faintly nasty. One day when I was at least forty I was lying in bed having another go at my half-buried past when I saw in detail the coverlet that had been on my cot when I was a baby. This had ribs of twisted white wool running across it, and round the edge was a lace border with small loops in it that I felt if I pulled the coverlet up to my chin. At the same time that I saw these details, I remembered that in this cot I slept beside my parents' bed. One night I heard my parents whispering. Then my mother called my name tentativelyexperimentally. I knew that on no account must I answer. The whispering began again and, after a while, my father gave a long, despairing groan. I was surprised at this because I had expected, not him, but my mother to be hurt. It is a pity that I cannot say that, when I recalled all this, the scales fell from my eyes and the meaning of my life was suddenly clear. I merely experienced a pleasant relief as though I had solved a clue in a long-abandoned crossword puzzle. The only practical use I ever found for this revelation was that it enabled me to answer with certainty one of the questions that doctors and psychologists always asked me. Did my parents ever make love after I was born? I never know how they imagined I would be able to answer but I could.

Next page