Shakespeares COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS

Shakespeares COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS The Book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Age

DANIEL SWIFT

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research,

scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Daniel Swift 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Swift, Daniel, 1977

Shakespeares common prayers : the Book of common prayer

and the Elizabethan age / Daniel Swift.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-19-983856-1

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Religion.

2. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Sources.

3. Religion and literatureEnglandHistory16th century.

4. Religion and literatureEnglandHistory17th century.

5. Prayer in literature. 6. Religion in literature. I. Title.

II. Title: Book of common prayer and the Elizabethan age.

PR3011.S95 2012 822.33dc23 2012005616

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For Leo  Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.

Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.

Learning cannot be too common, and the commoner the better. Why but who is not jealous, his mistress should be so prostitute? Yea but this Mistress is like air, fire, water, the more breathed the clearer; the more extended the warmer; the more drawn the sweeter.

JOHN FLORIO,

To the courteous Reader,

The Essays of Michael de Montaigne (London, 1603)

A Note on Texts

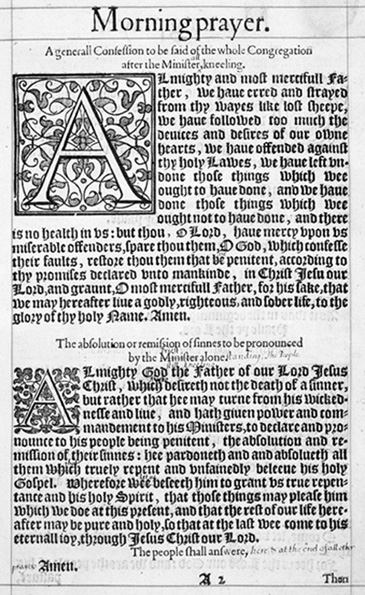

For most of Shakespeares lifetime, the 1559 version of the Book of Common Prayer was the official prayer book of the Church of England. In what follows, I quote from this version unless otherwise noted. Brian Cummingss edition of the Book of Common Prayer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011) collects the 1549, 1559, and 1662 texts, and this is the most convenient modern edition.

Shakespeares plays are quoted from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), unlessparticularly in the case of Hamletotherwise noted. References to Shakespeares plays are by act, scene, and line. The translation of the Bible that Shakespeare read and most frequently alludes to is the Geneva version. This will also therefore be my default version although the Book of Common Prayer was a vital and too-long unacknowledged place where Shakespeare, like all his contemporaries, encountered scripture.

I have lightly modernized the spelling of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century texts throughout: so that, for example, publique appears as public.

Shakespeares COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS

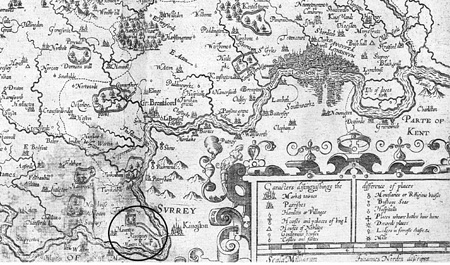

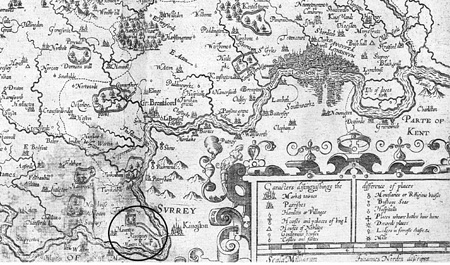

Hampton Court Palace, from William Camden, Britain: A Chorographical Description (1610).

PROLOGUE A Revel with the Puritans

A Revel with the Puritans In 1603, Elizabeth I died and King James of Scotland became the king of England. It was a season of change, of the old order passing. John Stow, updating his great chronicle of England, noted the spread of plague in divers parts of this realm, notably the City of London, and estimated that thirty thousand had died in this most recent outbreak. God make us penitent, he wrote, for he is merciful. At the end of the year there were unusually thick mists. That winter at Hampton Court Palace, twenty miles upriver from London, the new king summoned representatives from two different worlds. He called to a conference religious men, bishops, and preachers, the orthodox and the radical, and he called men of the theater, players and playwrights alike.

The Hampton Court Conference may now seem a minor episode in the great sweep of British history, and is perhaps most famous as the occasion at which the new King James Version of the Bible was commissioned. This was completed in 1611, now a little more than four hundred years ago. But the conference was a great affair, much-discussed, much-anticipated, and its consequences ran wide. It had been called in response to a Puritan petition for further reformation of the English Church, and in particular the revision of the Book of Common Prayer, which set out the official rites and forms of public devotion. This was the central religious text of this powerfully religious age, and at his palace by the river the king, his bishops, and the Puritans came together to resolve the issue of what to revise. These were not the only visitors. As was customary, the holiday season in the royal household was marked by revels and performances of plays, staged by theatrical companies brought up from London. One name stands out today: William Shakespeare was at Hampton Court Palace at Christmas 1603.

The clash of these different worlds was not lost upon the king. Reflecting upon his first winter in England, James wrote to the Earl of Nottingham: We have kept such a revel with the Puritans here this two days, as was never heard the like. The joke suggests the mismatch between revels and Puritans, and perhaps reveals also his pleasure in this unusual meeting.

If you had been at Hampton Court in the winter of 1603 and were asked what would echo down the centuries as the remarkable event of the season, you would not say the performances by Shakespeare. You would say the Hampton Court Conference; that this may sound odd today is only a sign of our distance from the world in which Shakespeare moved and wrote, and which first looked upon his plays. If you wish to understand Shakespeare, then Hampton Court Palace in the winter of 1603 is a good place to start: at the meeting of the great playwright and the revision of the most contested literary work of the age, the Book of Common Prayer.

Next page

COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS

COMMON PRAYERS

Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.

Grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.